Craft: Avoidance

Saunders, Babel, Jiménez, Gornick, "The Sweet Obsession Bleeds from Singer," "Ancestors who Came to New York From an Extinguished Past," "Who's Sorry Now"

In my editorial services work I often encounter stylistic tics that poets use when they get stuck, find an obstacle, a loose thread, a dropped stitch, a psychological uncertainty, a moment of abrasion, or a moment of tension in a poem. They don’t know what to do.

These markers include rhetorical questions, mixed metaphors, abstract nouns, two or more adjectives in front of a noun, explaining what was just said more directly in previous lines, or some cliché or cliché-adjacent set of dead words.

When the poet gets stuck, instead of approaching what’s getting them stuck head-on, they resort to such devices or quirks because they haven’t fully touched whatever psychological or intellectual block they met when approach the subject or object of the poem. George Saunders recently wrote about this issue in terms of fiction. It’s a form of avoidance.

Emptying

Avoidance literally means “the emptying of vessels,” and instead of approaching something that is overthought, uncomfortable, or misunderstood, the poet will not be able to approach the thing fully; instead, they will avoid it, try to get around it rather than through it, or hope the reader won’t notice. In other words, they will empty themselves of dealing with the stickiness of the poem instead of working through it.

It’s really an act of nullifying or rendering void the difficult engagement with the raw material. Sometimes these stylistic glosses, or craft moves, might seem poetic, but they are often superficial or decorative.

A few examples:

The rhetorical question.

These are questions for which the poet already knows the answer. The poet want the reader to reveal their feelings without the poet revealing their own. In a sense, this is a form of bullying because the emotional risk is not balanced or implies scorn.

(e.g. “Am I healed?” “Whose fear is this?” “What remains unsaid?”)

Too many adjectives or adverbs.

Isaac Babel said: “If you can’t find the right adjective for a noun, leave it alone. Let the noun stand by itself. A comparison must be as accurate as a slide rule, and as natural as the smell of fennel….A noun needs only one adjective, the choicest. Only a genius can afford two adjectives to one noun…We all ought to take an oath not to mess up our job.”

Breeziness.

This is a talky, casual, or folksy voice meant to be convey warmth, full of fun, and familiarity. It’s a stylistic marker of the egocentric who imagines their every thought is interesting.

(e.g. “The truth is,” “I think,” “You know,” “I swear,” “I remember”)

Abstractions.

(e.g. “misery,” “justice,” “future”)

Avoidance is the result of either fear or shame; the internal and external pressures to finish the poem means fear or shame come into the poem, but in a way they can be glossed over.

Literature is translation; poetry, original

Poets are typically discontented people, and one goal of a poem is for the poet to change themselves for others. Avoiding the direct confrontation with part of the poem that makes you stuck also means that you imagine the poem is be holistic, or complete, like a circle. However, with such knotty material, a half-resolved, difficult point in the poem presents a path, or way forward.

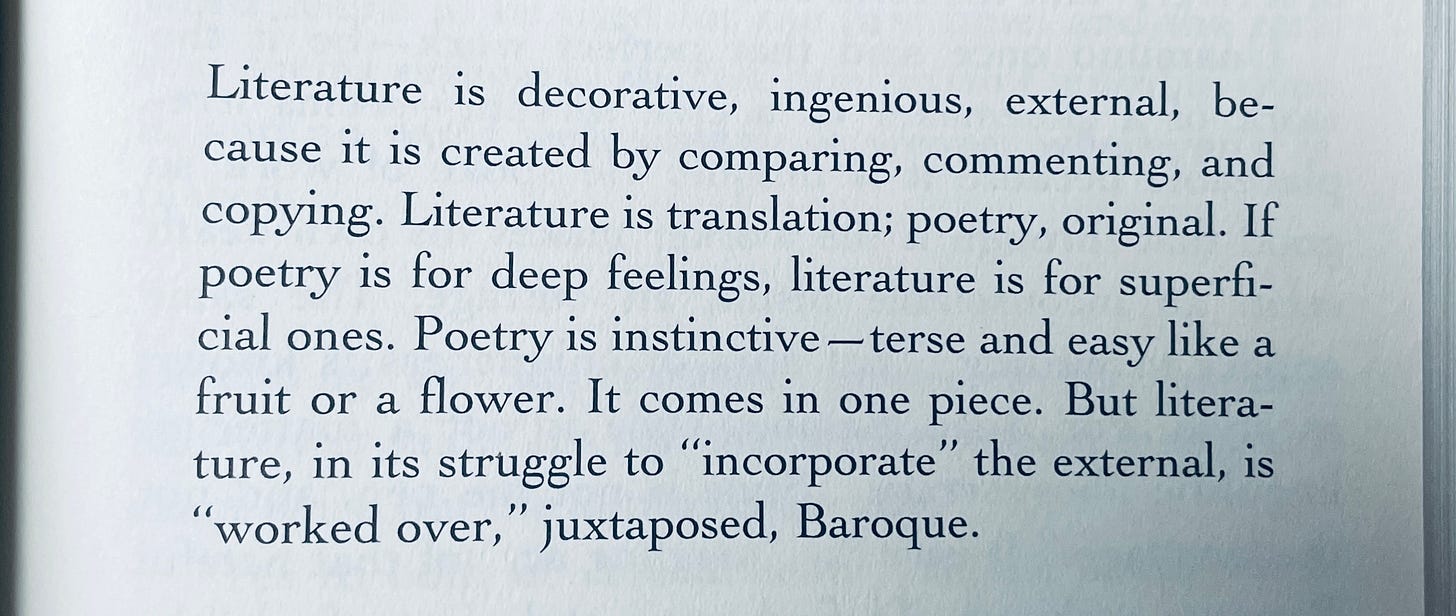

Juan Ramón Jiménez, in discussing being instinctive and dealing with such difficulty, said:

The distinction between literature and poetry might help us think about how to unstick those raw moments in a poem, to make them what W.S. Merwin called “untrammeled.” Untrammeled means a poem’s innate right to freedom.

This means freedom to allow psychological sturdiness, to give yourself permission to be exposed as you lie on the couch in the open. Freedom to function as a tool, to promote change, to promote difference, to be unifying.

Becoming the language of a poem feels like a secret process: to allow the poem to be too much and not enough, to be a poem that lusts to be wet, to allow the sea-stuff of memory and feelings to dry and become part of the shore.

Detached empathy

Vivian Gornick in The Situation and the Story, explains the need to express “inappropriate longings, defensive embarrassments, anti-social desires” through some kind of subterfuge:

Managing avoidance

In my own poems I’ve tried a handful of different ways of managing avoidance:

A character or persona.

In my book Discography, I invented a character named Singer who has permission to say and do things I would not want to bring too close to the surface. The Singer character creates a thin layer of psychic distance between me and the subject.

The poem begins with Singer’s death, a subject I would not want to think about directly. The speaker observes Singer from a third person position, but then in the middle of the poem Singer writes a poem within the poem. So, my poem contains Singer’s poem which is in a box, as if on a slip of paper.

Changing perspectives and emphasizing porousness.

Elsewhere, I feel more open to the porousness of the subject. Here, the Singer character is not a person or persona, but a real place, a bar in the former Jewish Quarter of Kraków, Poland:

The poem begins by looking down on Ellis Island from above, then moves to negation: I am not my great-grandparents who arrived there. Markers of their immigrant status (black wool, lady’s-shoe-heelism, inky tea) become part of the landscape. This landscape then moves forward in time, but back in geography: to Eastern Europe. Finally, a girl appears, perhaps the poem herself: the annihilation of the Jews as “human vapor,” and her message becomes easily erased: “the grey spine of a penciled world.”

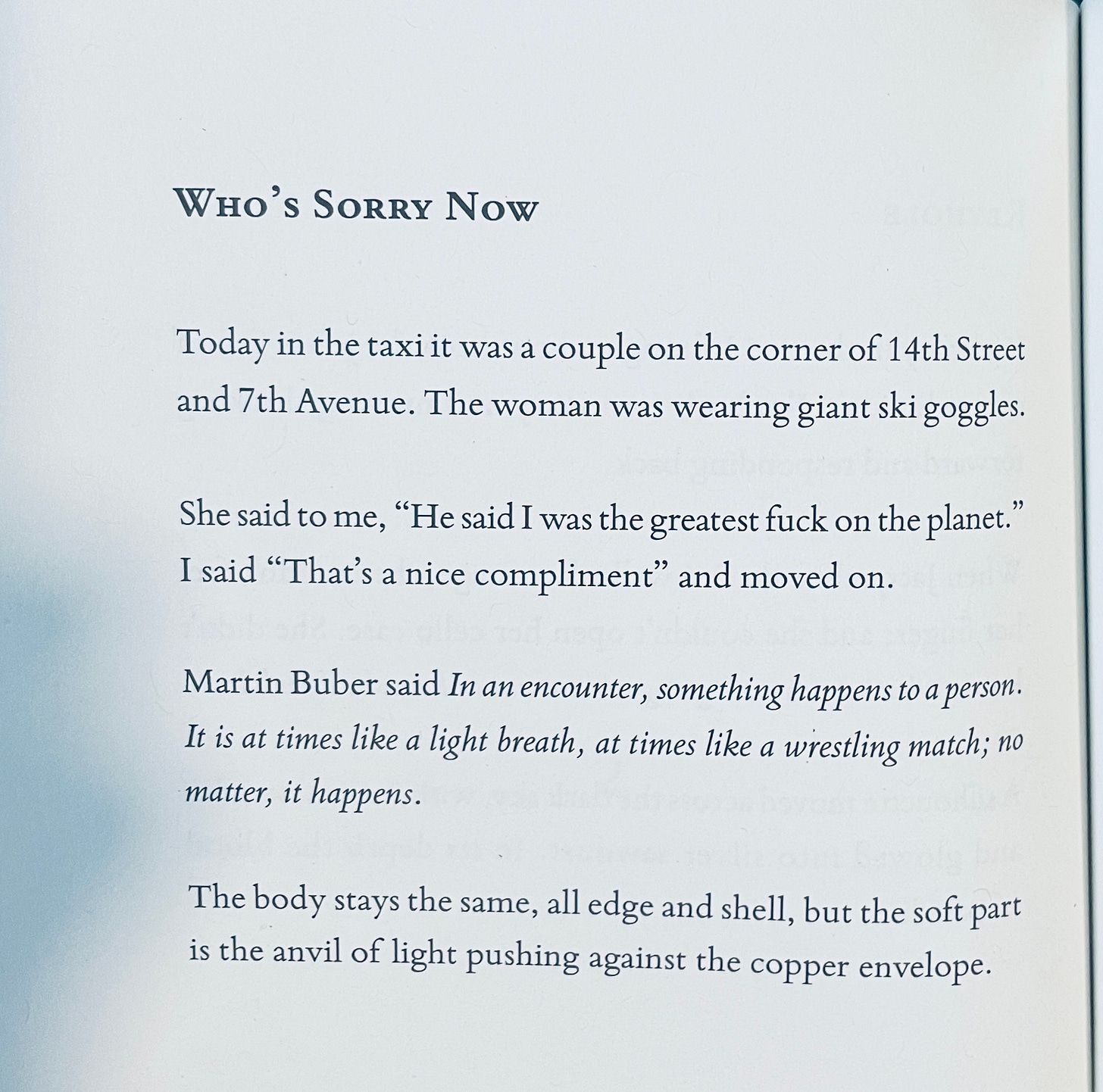

Fragments and attention to outside voices.

Other times, I seek other, external voices (people, texts, visions). In this way the self reflects, rises, or diminishes in relationship to those voices.

This poems invokes Martin Buber, the Austrian-Jewish philosopher, to bring a voice not my own, but might sharpen or refine the self. The juxtapositions of the subjects lift something banal to something more disturbing, hopeful, tender, or wounded.

Avoidance is accompanied by actions: clearing away, removal, ejection, excretion. It is also an outlet for feelings: invalidation and annulment. Part of the enormous effort of making a poem is not just choosing the right words, finding the form, and being yourself, and making metaphor. It is also noticing where these moments of avoidance occur in the poem.

Sometimes this is a technical problem with a technical solution, but often the solution requires a further digging-into the self.

For further reading:

Gornick, Vivian. The Situation and the Story: The Art of Personal Narrative. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002, p. 7. [Buy on Bookshop]

Jiménez, Juan Ramón. The Complete Perfectionist: A Poetics of Work. Spain: Swan Isle Press, 2011, p. 145. [Buy on Bookshop]

Prose, Francine. Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them. New York: Aurum Press, 2012, p. 263-264. [Buy on Bookshop]

Singer, Sean. Discography. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, p. 78. [Buy on Bookshop]

—. Honey & Smoke. London: Eyewear Publishing, 2015, p. 32. [Buy on Bookshop]

—. Today in the Taxi: Poems. North Adams, MA: Tupelo Press, 2022, p. 24. [Buy at Tupelo Press]

About Sean Singer

"A comparison must be as accurate as a slide rule, and as natural as the smell of fennel..." Thanks, Sean...

"Part of the enormous effort of making a poem is not just choosing the right words, finding the form, and being yourself, and making metaphor. It is also noticing where these moments of avoidance occur in the poem." Yes. Thank you.