This essay is reprinted from July 9, 2022. I am offering it to all subscribers.

Bob Kaufman (1925-1986) was a peripheral Beat figure, whose work was highly idiosyncratic with both Surrealist and jazz influences. He was the tenth of 13 mixed Jewish and Black children. Though he was born in New Orleans, he is most associated with San Francisco, and the poetry that came from there in the 60s and 70s, mostly from the City Lights Bookshop.

Kaufman thrived among the Beat artists in San Francisco, an important group who included Jack Spicer, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Philip Lamantia, John Wieners, Jess, Robert Duncan, Stan Brakhage, Harry Smith, Jay DeFeo, Gary Snyder, Joanne Kyger, Wallace Berman, Rachel Rosenthal, and Anna Halprin.

Kaufman was peripheral because he was Black, he was Jewish, and his poems were more political than those of the rest of the Beats. Kaufman coined the word “beatnik” because the police had a vendetta against him and arrested and “beat” him 37 times.

He published three books in his lifetime: Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness (New Directions, 1965), Golden Sardine (City Lights, 1967), and The Ancient Rain (New Directions, 1981).

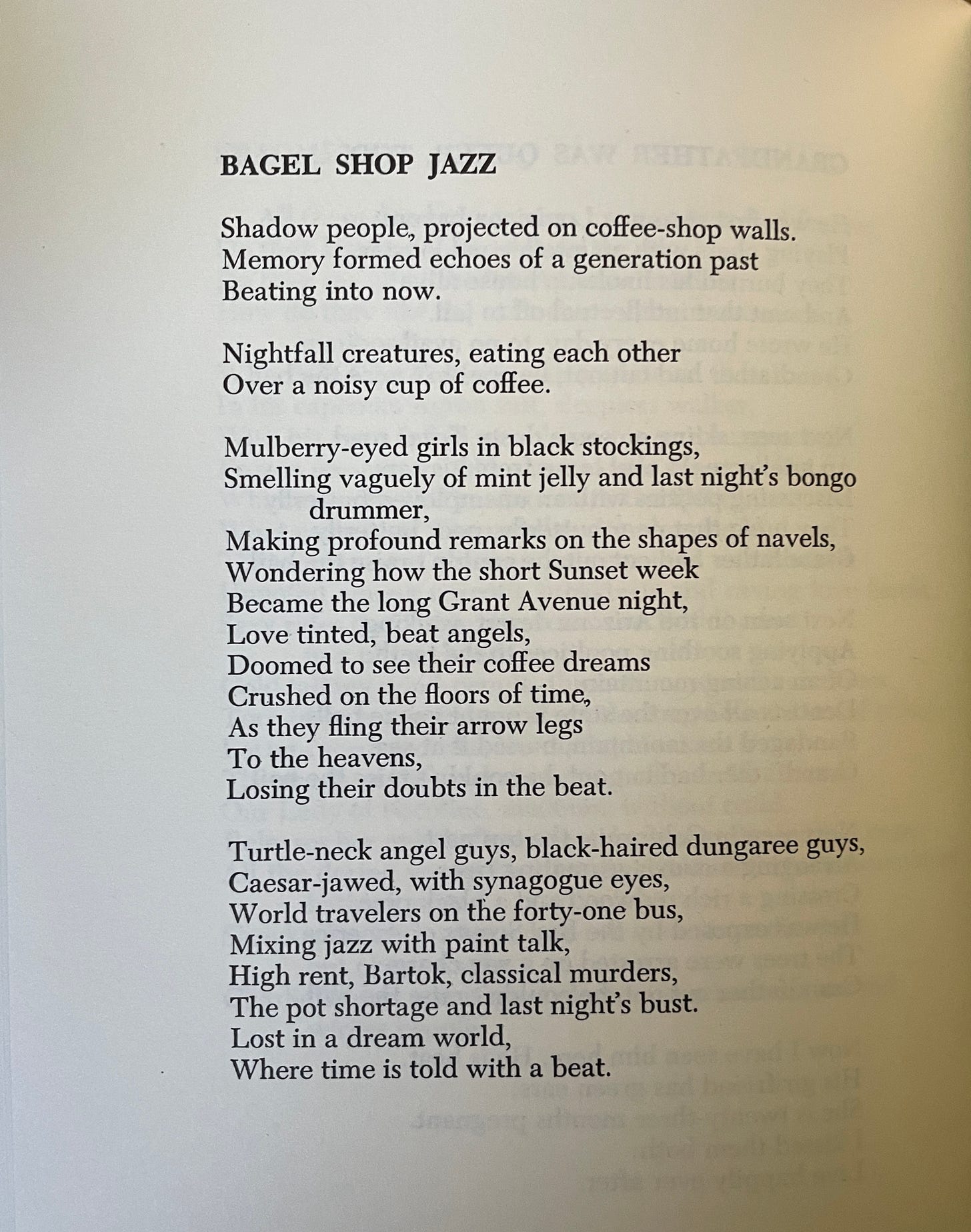

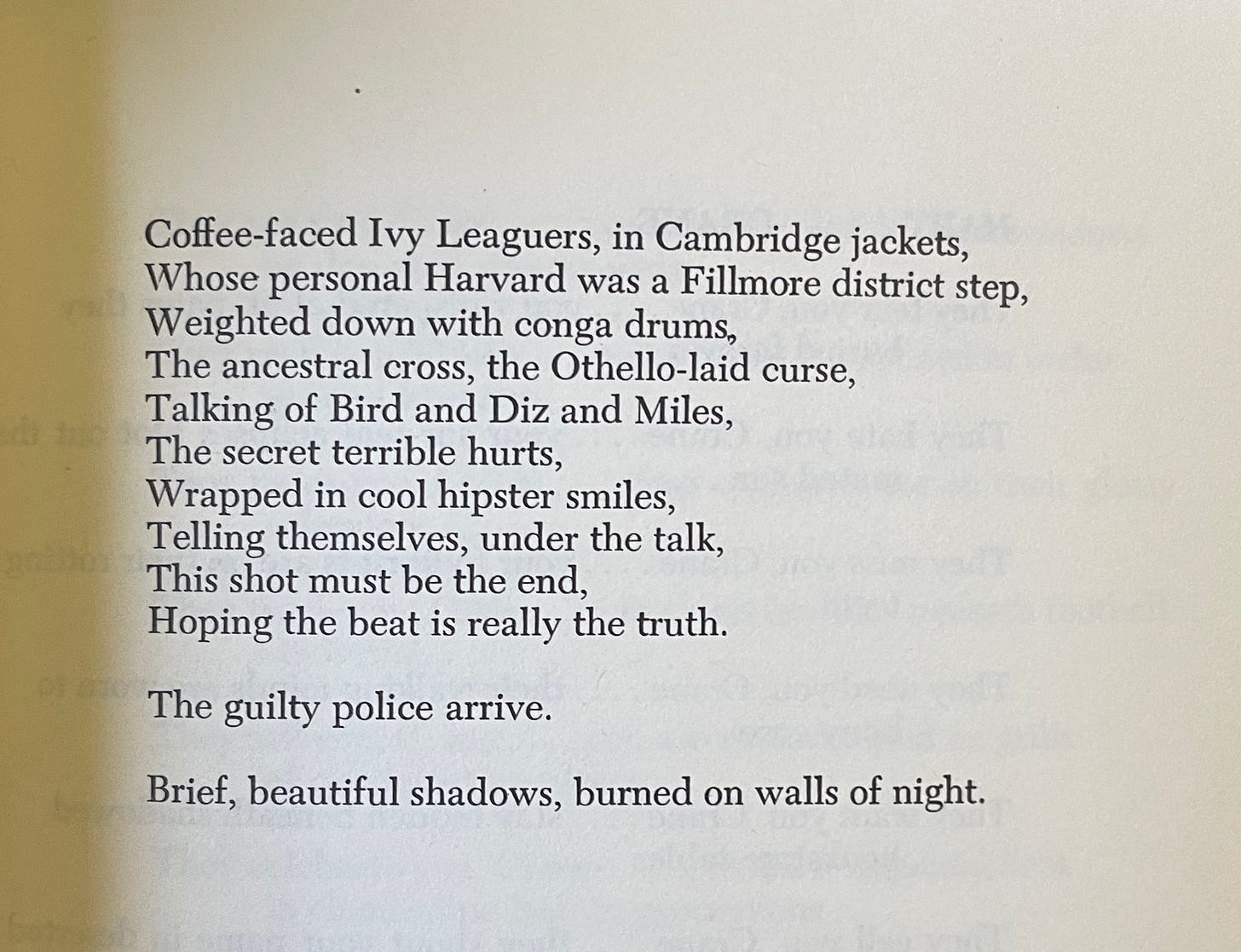

“Bagel Shop Jazz” shows his mastery of fusing the political with the immediacy of physical experience through a lens of Surrealism.

Kaufman’s leftist politics got him into constant difficulty. For example, he wrote and posted on the coffeeshop wall—“When the Nazis got tired of burning Jews, they became cops in San Francisco.” He was arrested for narcotics, public drunkenness, disorderliness, walking on grass, protesting, and supporting Communism.

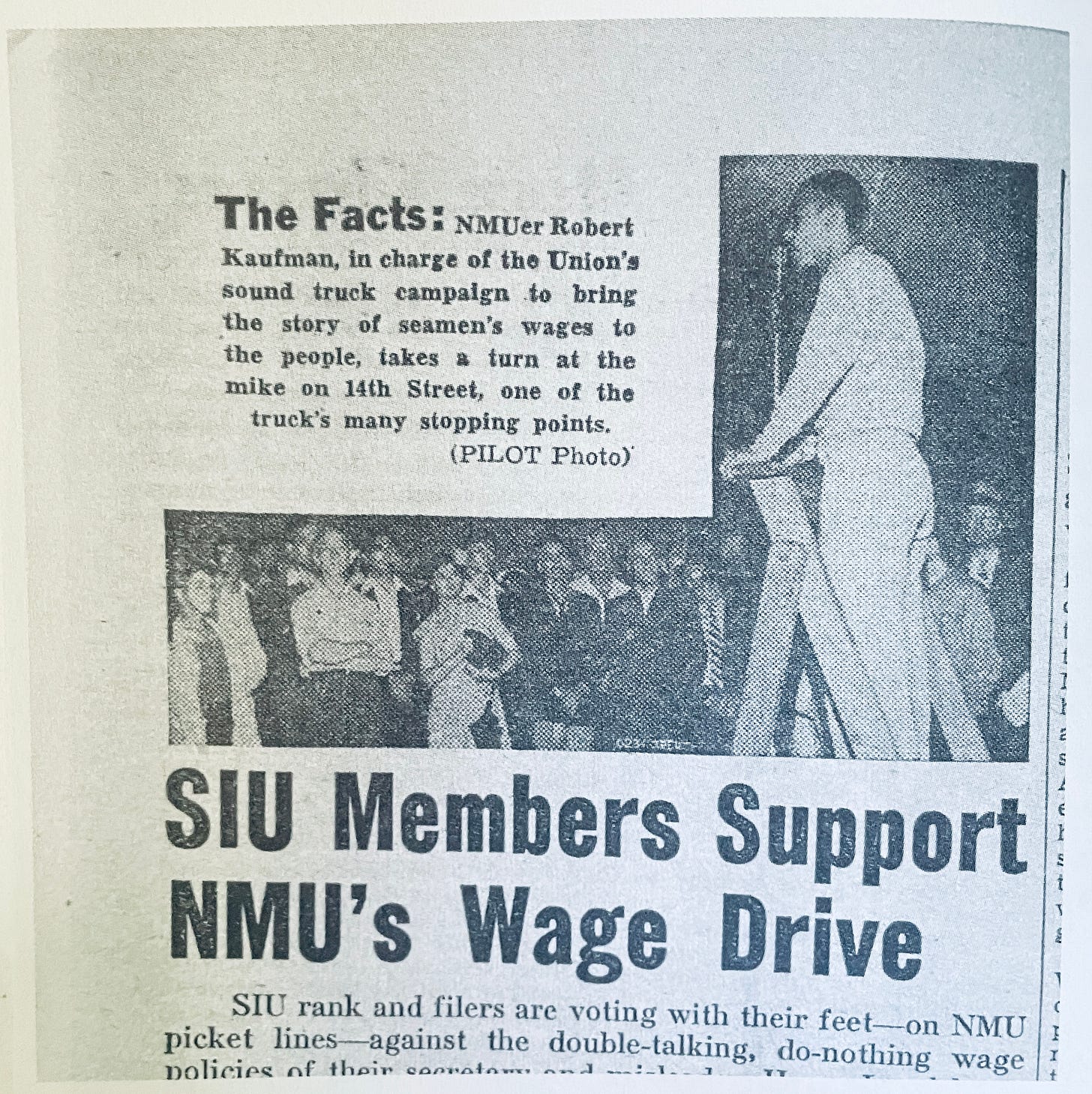

Kaufman was the Chairman of the Rank and File National Maritime Union (NMU), which was one of the most leftist, pro-Civil Rights union with many Black and immigrant members. In 1946, the FBI’s file on Kaufman identified the NMU as a Communist organization, and as McCarthyism became ascendant, they barred Kaufman and many other Black members from working in any port as a way to exclude them from the workforce.

In 1947, Kaufman published two letters in The Pilot, the NMU newspaper denouncing the “hysterical campaign against the Communist Party” by the House of Un-American Activities. The FBI visited Kaufman’s apartment on Longwood Avenue in the Bronx and interviewed his estranged wife, Ida Berrocol (they divorced in 1954) and also his mother. By 1951, he was declared to be a security risk by the U.S. Coast Guard and was expelled from NMU for drug use.

He moved to San Francisco, and became a primary fixture in North Beach where the San Francisco / Beat poetry renaissance was happening. He met Eileen Kaufman (née Eileen Singer) in 1958 and they had a son, Parker (named after Charlie Parker) in October 1959. They came to New York in 1960, but towards the end of their visit, Kaufman was arrested and involuntarily taken to Bellevue Hospital where they administered involuntary shock treatment. He was arrested again in 1962 and sent to Riker’s Island Prison.

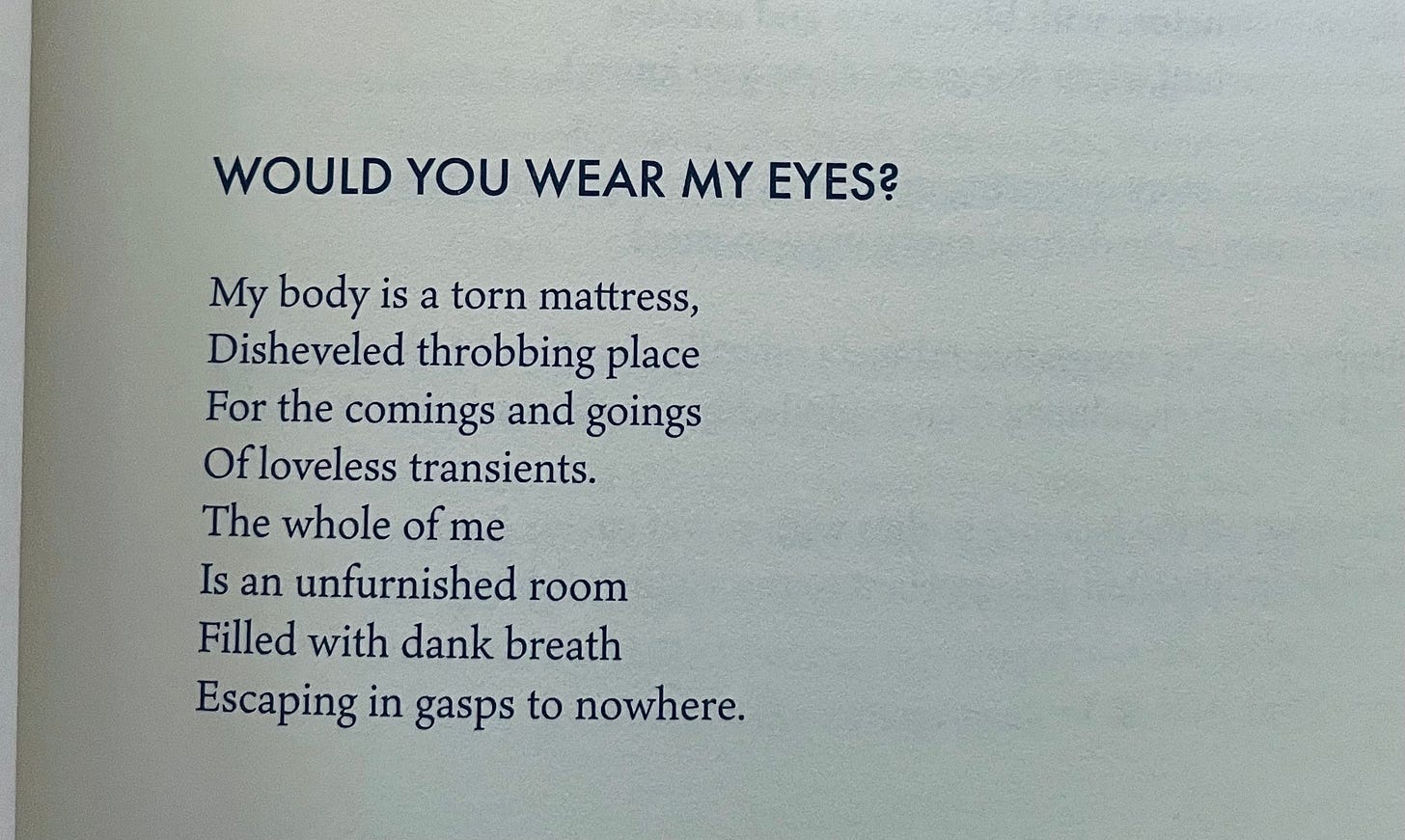

“Would You Wear My Eyes?” is so porous that it moves through many mysteries, but it is also evocative of his experiences of psychological and physical imprisonment.

When President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, Kaufman supposedly made a vow of silence and did not have a conversation until May 31, 1973. Amiri Baraka, one of the few Black figures in the Beat Movement described Kaufman as the most extreme, most uncompromising of all the Beat poets—uncompromising in the sense of making absolutely no concessions to the bourgeoisie.

Kaufman’s more fully than Ginsberg became his language, so much so that even during his vow of silence, he could channel his main influences: Federico García Lorca and Hart Crane.

Kaufman’s poems are political, bluesy, jazzy, surreal, immediate—they always form openings between the physical part of the world and the mystery or unknowability of the world.

The Beat movement is often perceived as a white cultural movement because many of its primaries were white (besides Kaufman, Allen Ginsberg was also Jewish). But Kaufman in his life and work embodied the complete Beat ethos. His voice prefigures the current trend of poems that orbit identity. Being both Black and Jewish, he was doubly an outsider in both society and in poetry. Though the Beat Generation excluded him from their own anthologies, he is in fact responsible for the entire ethos.

“Grandfather Was a Queer, Too” shows Kaufman’s absolute attention to connecting the self to bigger questions: history, the vacuity of the world, and especially his unique language.

Kaufman’s poetry is a critique and celebration. It takes from jazz the capacity to choose to be joyful in spite of conditions. It takes seriously the belief that all labor comes from people’s bodies. Kaufman is “Beat” because he and his poetry are the ne plus ultra of the Beat aesthetic: what Baraka called in his autobiography “the open and implied rebellion of form and content.”

He was the most revolutionary of the Beats in his politics, too: Allen Ginsberg tried to levitate the Pentagon with bongo drums and chants; Jack Kerouac became a reactionary during the Cold War, was a fan of William F. Buckley, Jr., and supported the Vietnam War; William S. Burroughs killed his wife Joan Vollmer; Amiri Baraka left his family and became a Black Nationalist and began producing homophobic, anti-Semitic, and misogynist verse. Meanwhile, Kaufman lived his whole life in support of workers and using art to speak truth to power.

For further reading:

Kaufman, Bob. Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2019. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

Great stuff - thanks for the deep dive into Kaufman's work. Thoroughly enjoyed it.

I also really liked the language.