David Schubert (1913-1946) was an overlooked and underrated poet who suffered so much from depression that he destroyed most of the poems he made. “Poets must sometimes look at themselves in order to remember what they are risking,” he said, and his brief life shows enormous risk. Only one book, Initial A, was published posthumously in 1961, and his poems have been mostly out of print since. In 1983, Quarterly Review of Literature made a 40th anniversary edition, also out of print, called Works and Days, that contained all extant letters and poems.

Schubert was always a young person, and never got to be old. He died of tuberculosis at 33 in Central Islip Psychiatric Center after a breakdown. He was dealt a losing hand, and if everything was different from the way it was, he’d be as significant as Robert Lowell or John Berryman, his contemporaries. Schubert’s devotion to poetry was all-consuming. It was his pressure valve, and his only interest and purpose. James Wright called him “a master of silences and a most discriminating listener.”

Schubert was born into poverty. In 1925, when he was 12, Schubert’s father left the family and his mother killed herself. Young David discovered her body. Schubert was sent to live with relatives, but was homeless at 15. He eventually won a full scholarship to Amherst College, where Robert Frost encouraged his poetry and even gave him a stipend of $3 a week. (Frost taught at Amherst from 1917 until his death in 1963). Schubert’s severe depression forced him to lose his scholarship and drop out.

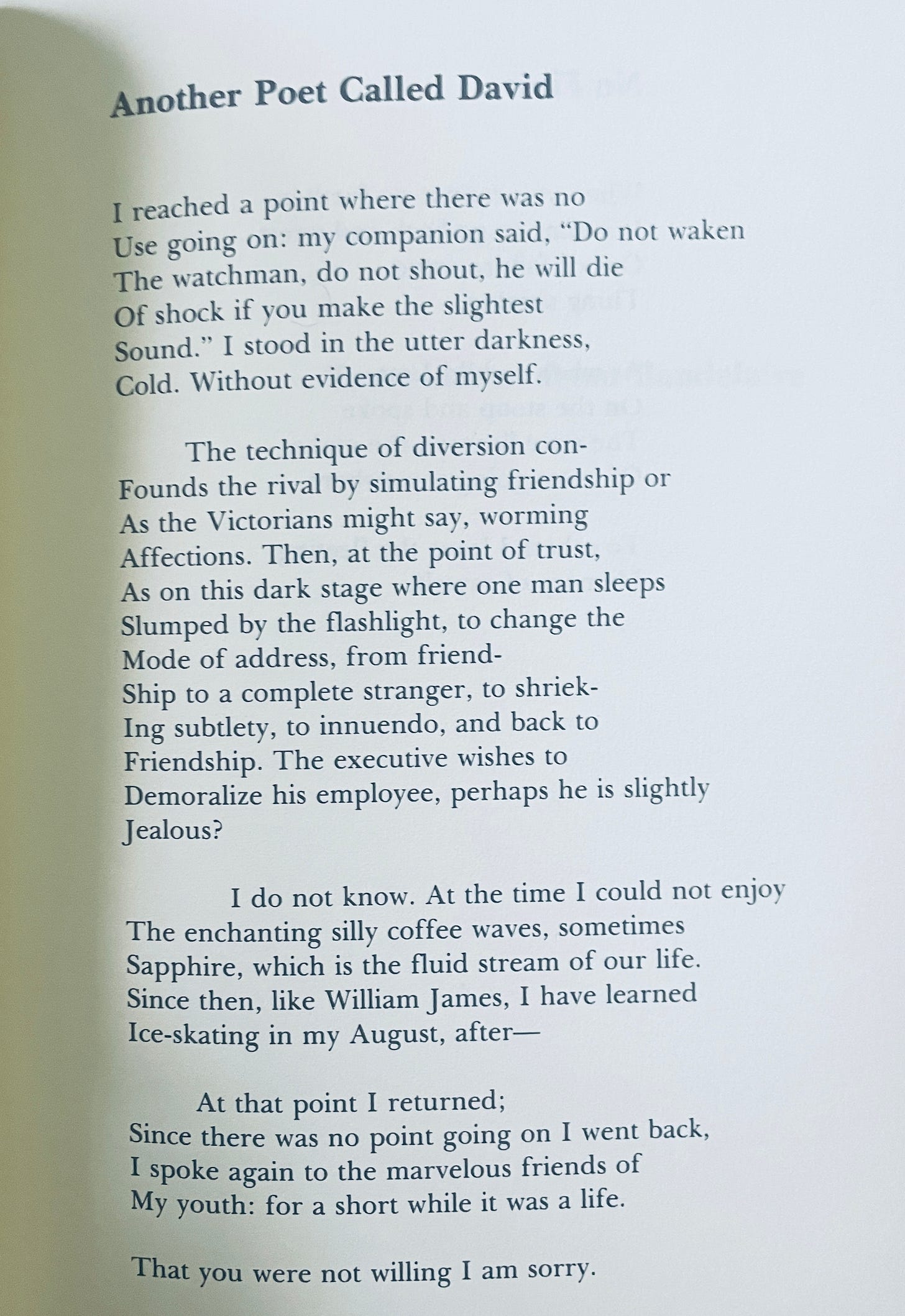

I reached a point where there was no

Frost told Schubert that “a poet—his arms can go out—like this—or in to himself; in either case he will cover a good deal of the world.” Besides covering the world, Schubert was a master at making poems out of the part of the world that is hard to write about—the inexpressible.

“Another Poet Called David” is a psychological self-portrait; it is about a broken self, a self who is doubted, a self who is perhaps hidden, contained, enforced.

Schubert’s way of breaking words in mid-word at line breaks is a strange, and intoxicating artistic choice: “con-Founds” and “shriek-Ing,” for example, are specific needle-points in the lines. It is almost as if the fractured self suggested by the title was experienced down through the bones into the veins and out again into the broken language.

William Carlos Williams, in a letter from July 16, 1942 to Schubert’s friend Theodore Weiss, wrote that “Schubert’s poems, they are first rate—more than that, far more…There is, you know, a physically new poetry which almost no one as yet has sensed. Schubert is a nova in that sky. I hope I am not using hyperbole to excess. You know how it is when someone opens a window on a stuffy room.”

Schubert supported himself by selling newspapers, working as a busboy, soda jerker, waiter, farm hand, and various other jobs. He also did itinerant farm labor for the Civilian Conservation Corps, but he never had an easy life. Sleeping at missions and shelters, he essentially did whatever he could to get by.

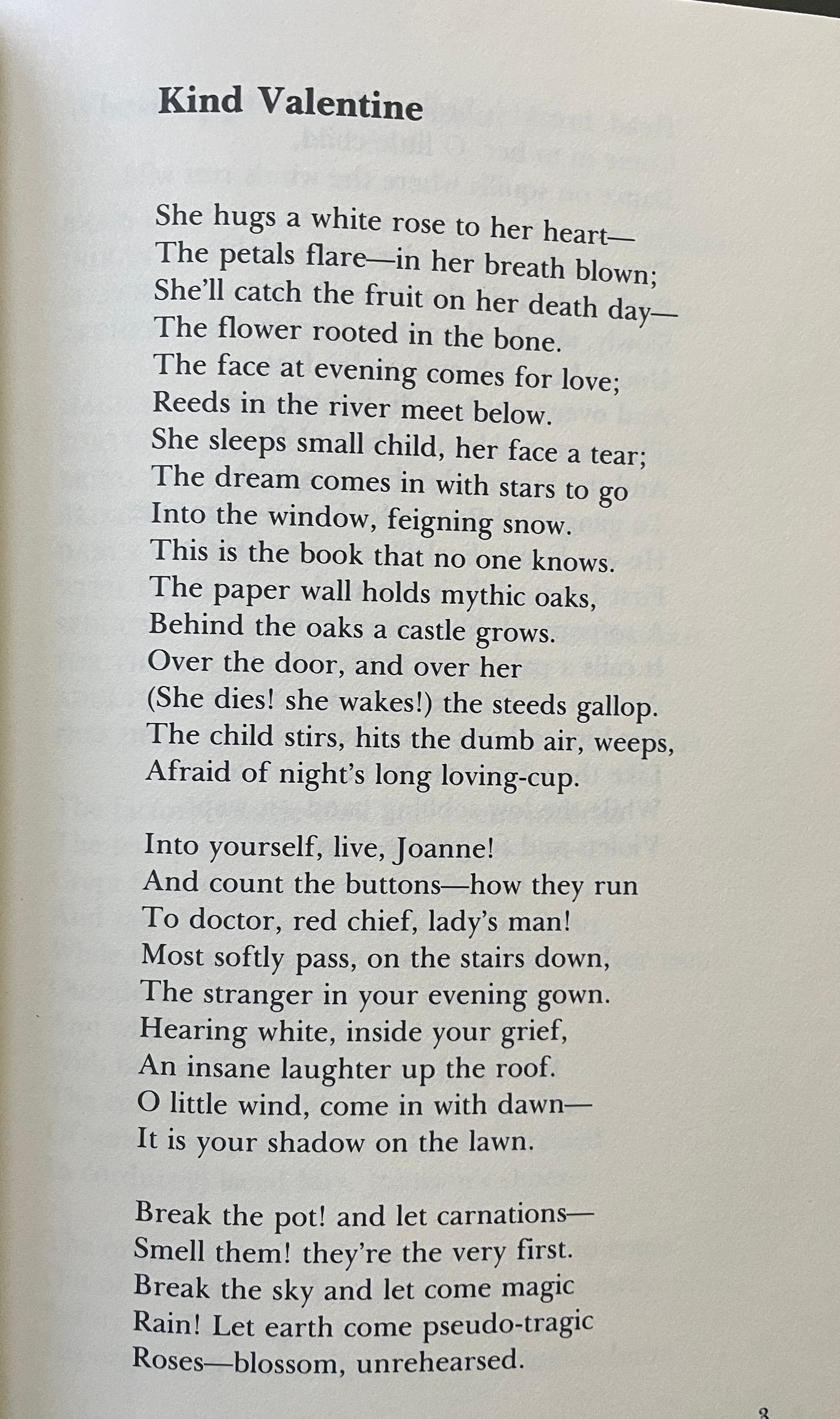

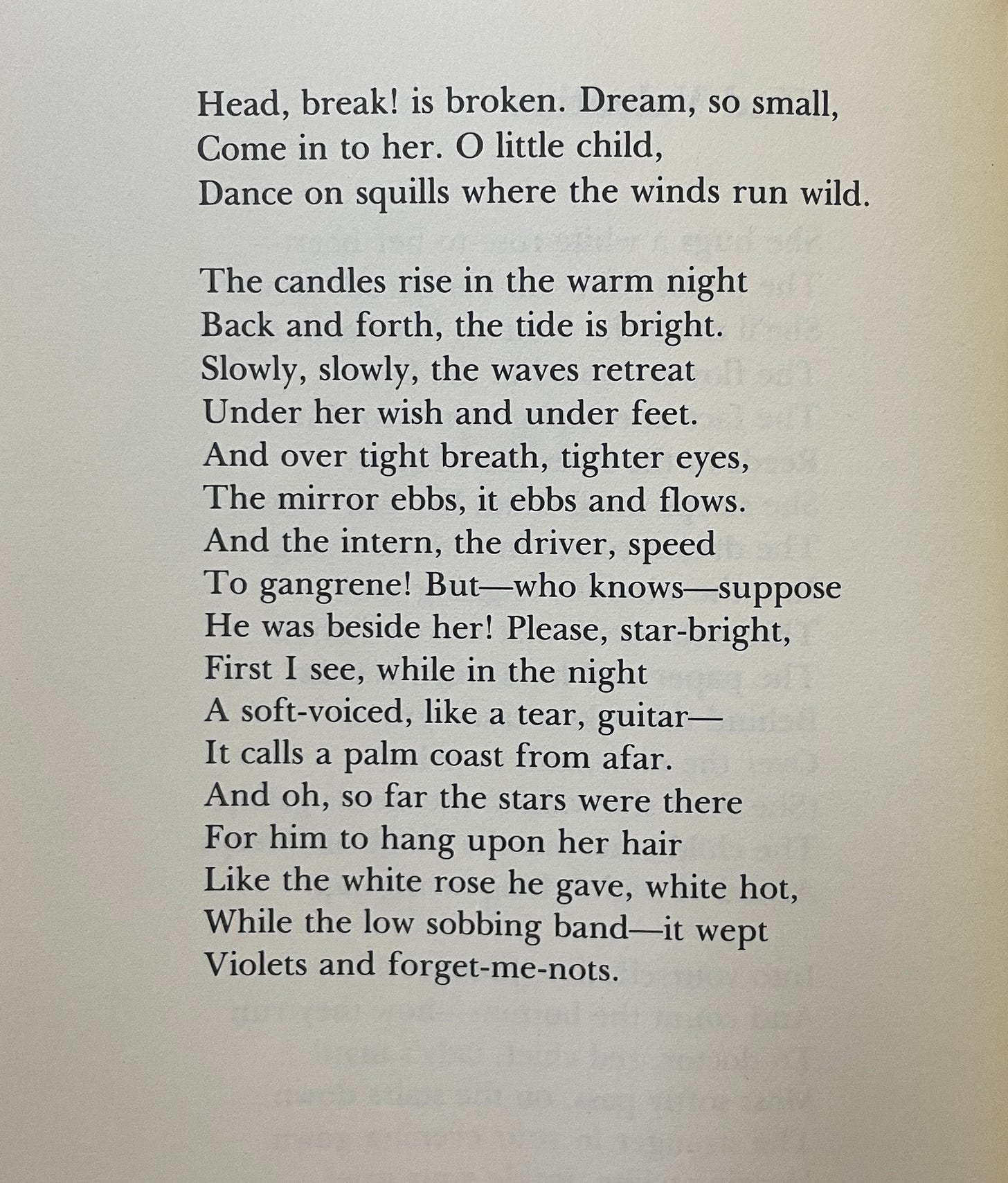

She hugs a white rose to her heart

When he was 20 he married a teacher, Judith Ehre, and they moved into an apartment at 110 Columbia Heights in Brooklyn Heights; the same apartment building where Hart Crane had lived beginning in April 1924. From then on they relied mainly on her teaching income, but Schubert was doing editorial work at the Brooklyn Institute for Arts and Sciences.

“Kind Valentine” is like a 20th century version of Keats. The idealized version of romantic love is filtered through a sieve of anguish: “Like the white rose he gave, white hot, / While the low sobbing band—it wept.” The poem uses rhyme effectively and subtly and the form is very well-balanced.

With more stability, he was able to finish his undergraduate degree at City College and a master’s degree in literature at Columbia. Schubert existed before there were psychotropic drugs, and he lived constantly with severe depression. Ehre wrote to Karen Horney who referred him to a psychiatrist.

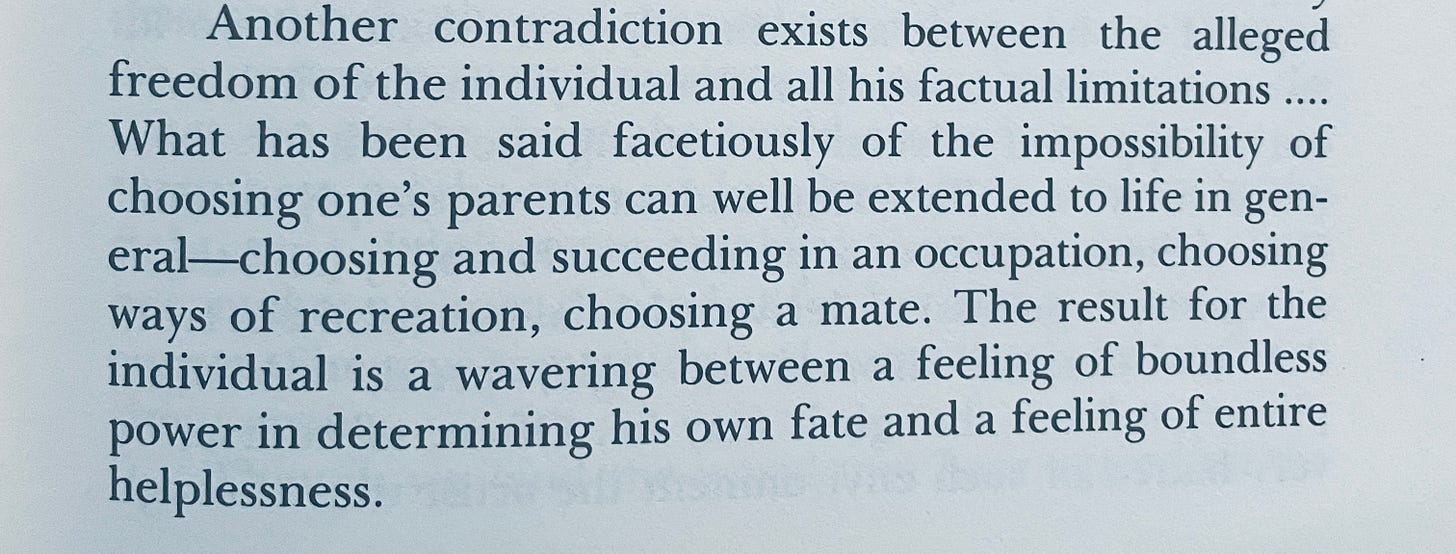

Horney wrote about Schubert’s living contradiction:

Schubert wrote in 1940 that “the desert years seem to cling to me more and more. Every once in a while I think I’m out of it, but there are so many places in each day in which one falls onto nothing at all. But I’m making a battle with the Enemy, anyway.”

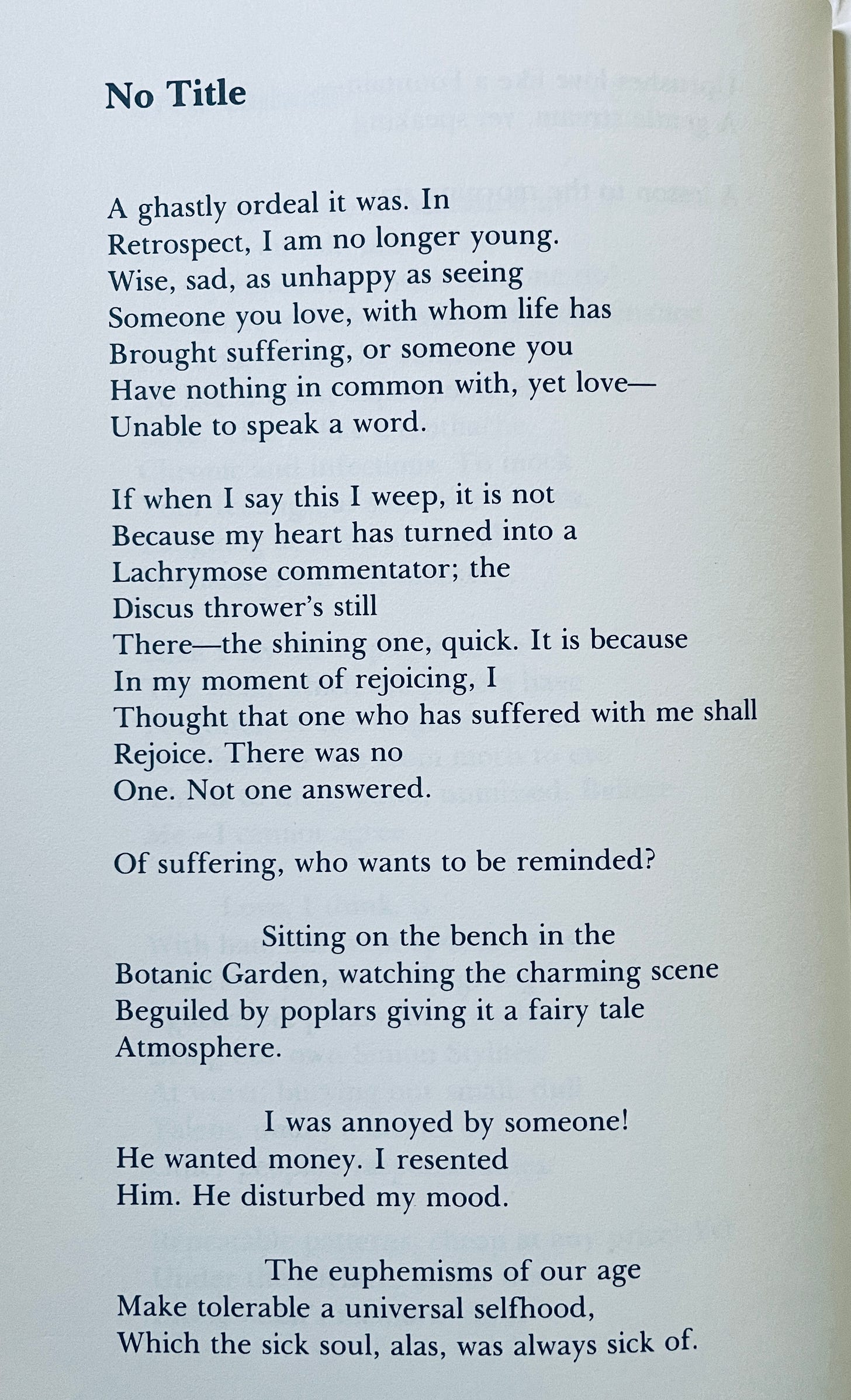

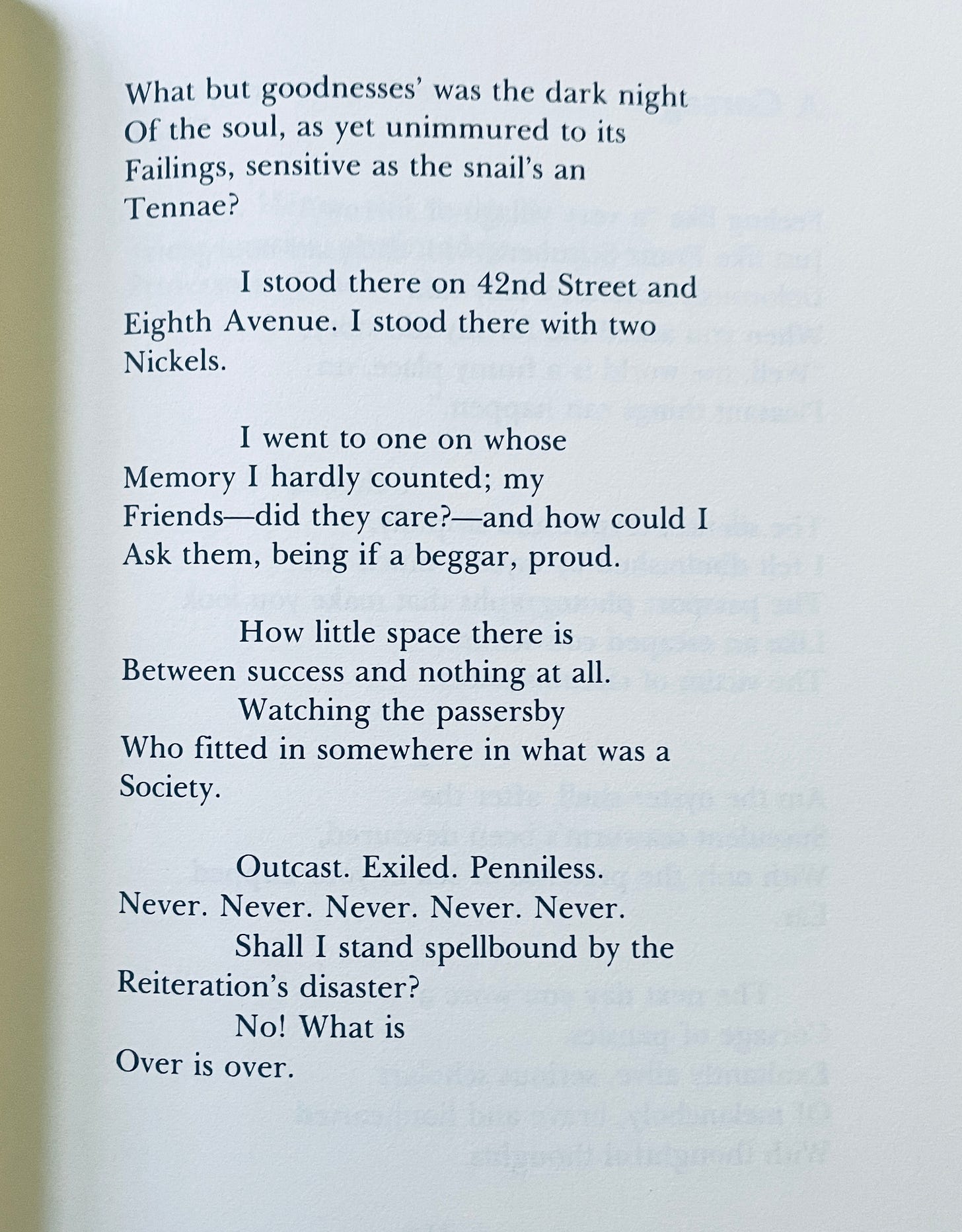

A ghastly ordeal it was

In 1941, David and Judith admitted to each other that they were each having affairs—David with one of his coworkers. The couple remained friends, but with moments of volatility. His mental health made him contemplate giving up writing frequently, even though he was getting published in places like The Nation, Parnassus, and Virginia Quarterly Review.

“No Title” has to be one of the most affecting and beautiful poems Schubert wrote. What kind of poem begins “A ghastly ordeal it was.” The passive voice implies that our fates and pressures are not always knowable or can be identified. The poem controls the emotions, showing loneliness as an active thing, a thing of exile and disaster.

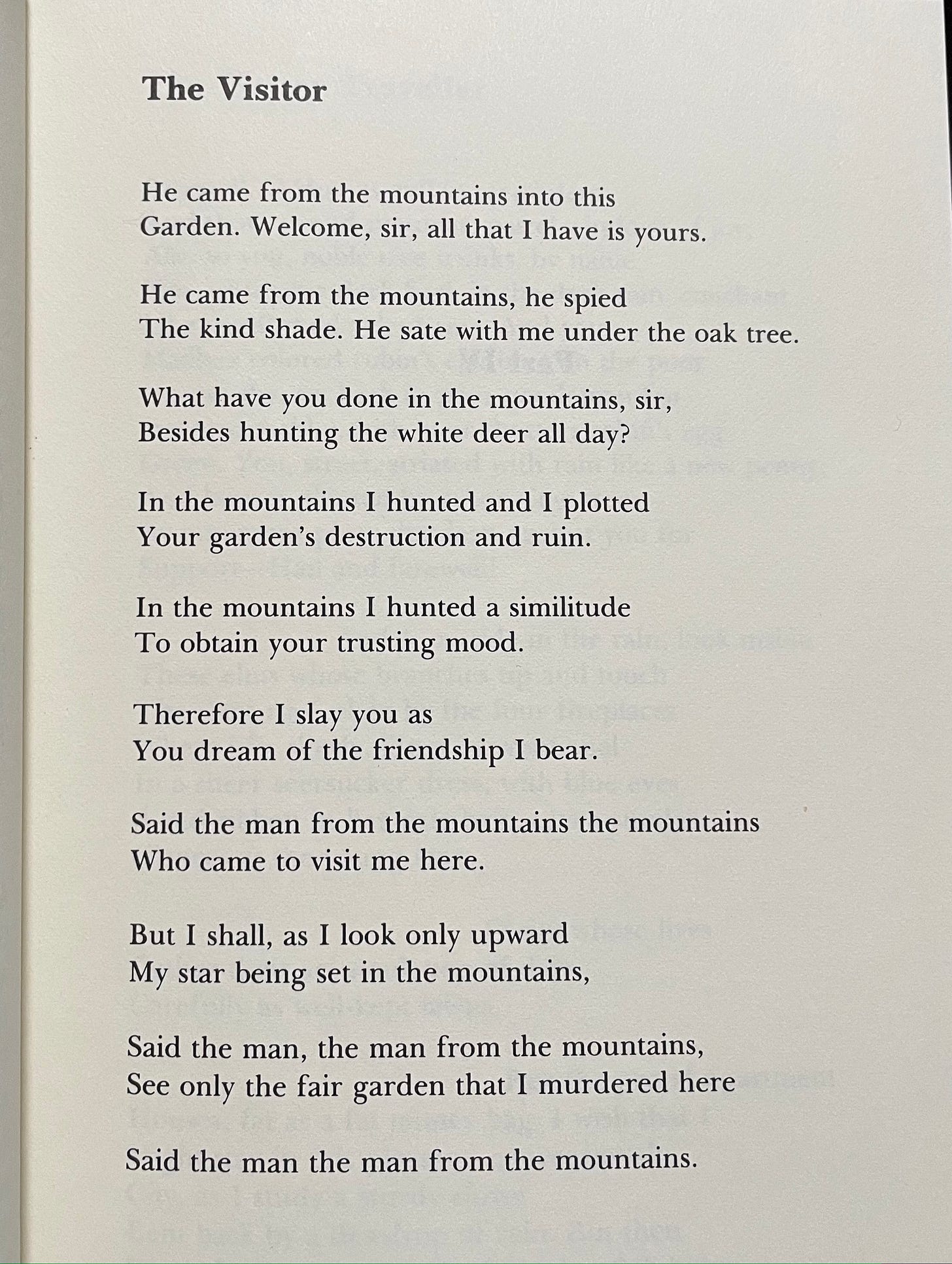

He came from the mountains into this

Schubert wrote that “what I see as poetry is a sample of the human scene, its incurably acute melancholia redeemed only by affection.” Reading the handful of poems that remain show the motions of his mind: empathetic, clear, pushing into the ambiguity of the self, the gulf between desire and fulfillment, the unspeakable mysteries that drive us forward or weigh us down.

One of his most enigmatic and painful poems is also the shortest. “The Visitor” could be about his tyrannical father, the visitor who all solid animosity. It is a violent poem, but set in the intimate peacefulness of couplets.

Imagine a world where the most interesting and committed poets are completely unknown, completely forgotten. A world where we’re only aware of the flavor of the month, oblivious to those who sacrificed everything for this thing, this craft, the poetry through which we live.

This is our world. David Schubert, Rosemary Tonks, Bob Kaufman, Lynda Hull—people mostly forgotten, unread, unstudied. These are the people to whom we should have monuments, squares, holidays, images on money, a tribute in our dreams of a better world.

There are no rewards in poetry. There is no meritocracy in poetry. There is only the energy of the poet transforming inert bricks of words into energy.

For further reading:

Ashbery, John. Other Traditions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000, p. 121-146.

Lenhart, Gary. The Stamp of Class: Reflections on Poetry and Social Class. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006, p. 47-53.

Schubert, David. Works and Days. Quarterly Review of Literature, Poetry Series, 40th Anniversary Issue, Princeton: QRL, 1983. [out of print]

About Sean Singer

Untreated depression is a tragedy. So is dying of TB. Having poetry as one's only outlet can be necessary but adds another level of danger. Destroying poems -- I'm not sure what that means.

It’s interesting...so many people tell young poets to stop writing self-pity poems. Certainly everyone told ME that. Then here you have a guy who created such impressive work and mentored by Frost no less, who encouraged his melancholic introspection. It’s just fascinating to me how much great poets can be examples of the opposite of the usual advice poets get.