This essay is republished from January 19, 2021. I am offering it to all subscribers.

Writing poetry is hard work. Stanley Kunitz called “the most difficult and life-enhancing thing a person can do.” But the hard work of poetry mostly happens unseen. When we’re reading finished poems in books or magazines, it’s rare that we get to see a draft, to see how the sausage actually gets made.

Poets often feel uneasy about sharing their drafts. It’s little like a magician who doesn’t want the audience to see the magnets and wires; the apparatus that makes the magic. It’s important to consider drafts. Poems are machines made of words. Looking closely at drafts can show us how they work.

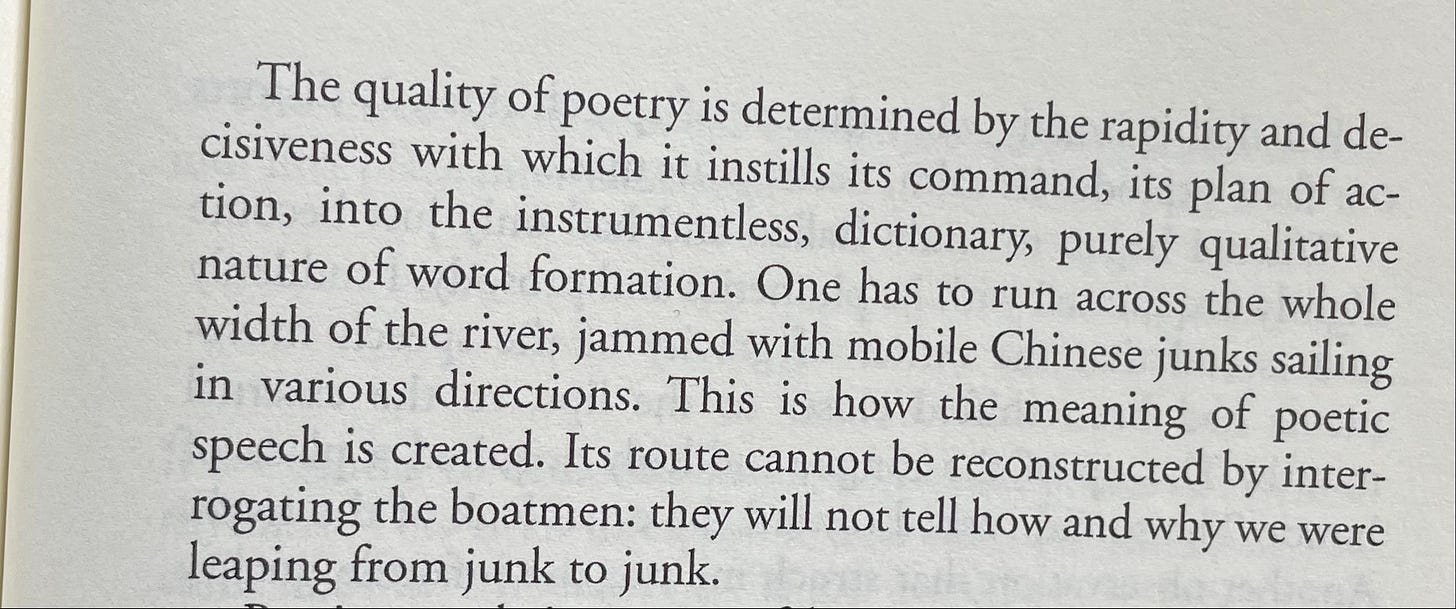

Osip Mandelstam, in his essay on Dante, used a fantastic metaphor for how poems are constructed: a person running “across the width of a river that’s jammed with mobile Chinese junks sailing in various directions.” The poet relies on their own movement and the movement of the language around and beneath them as they leap from junk to junk.

Mandelstam is talking specifically about the quality of poetry—the characteristics of the meaning of poetic language. Each poem has a unique texture—something more than voice—and each poet has a quality of energy that moves from poem to poem. However, each poem’s gestures must be carefully controlled. Gestures are chosen with deliberation because gestures are the principal means by which a poet can identify themselves as they emerge from the chamber within; the cave they can show no one, except through the flashlight of their poem.

Drafts can help us to see what is normally unseen (the rest of the cave). We can see the choices poets have made. Understanding their choices can help us to better understand our own.

Rukeyser’s “For My Son”

In 1948, Muriel Rukeyser published her series, “Nine Poems for the Unborn Child”. These poems addressed her experiences with pregnancy, and its social and personal implications. At 34, she was pregnant, unmarried, abandoned by the child’s father and rejected by her own family. These nine poems document Rukeyser’s transformation from “the childless years alone without a home” to a future where she was “To live, to write, to see my human child.”

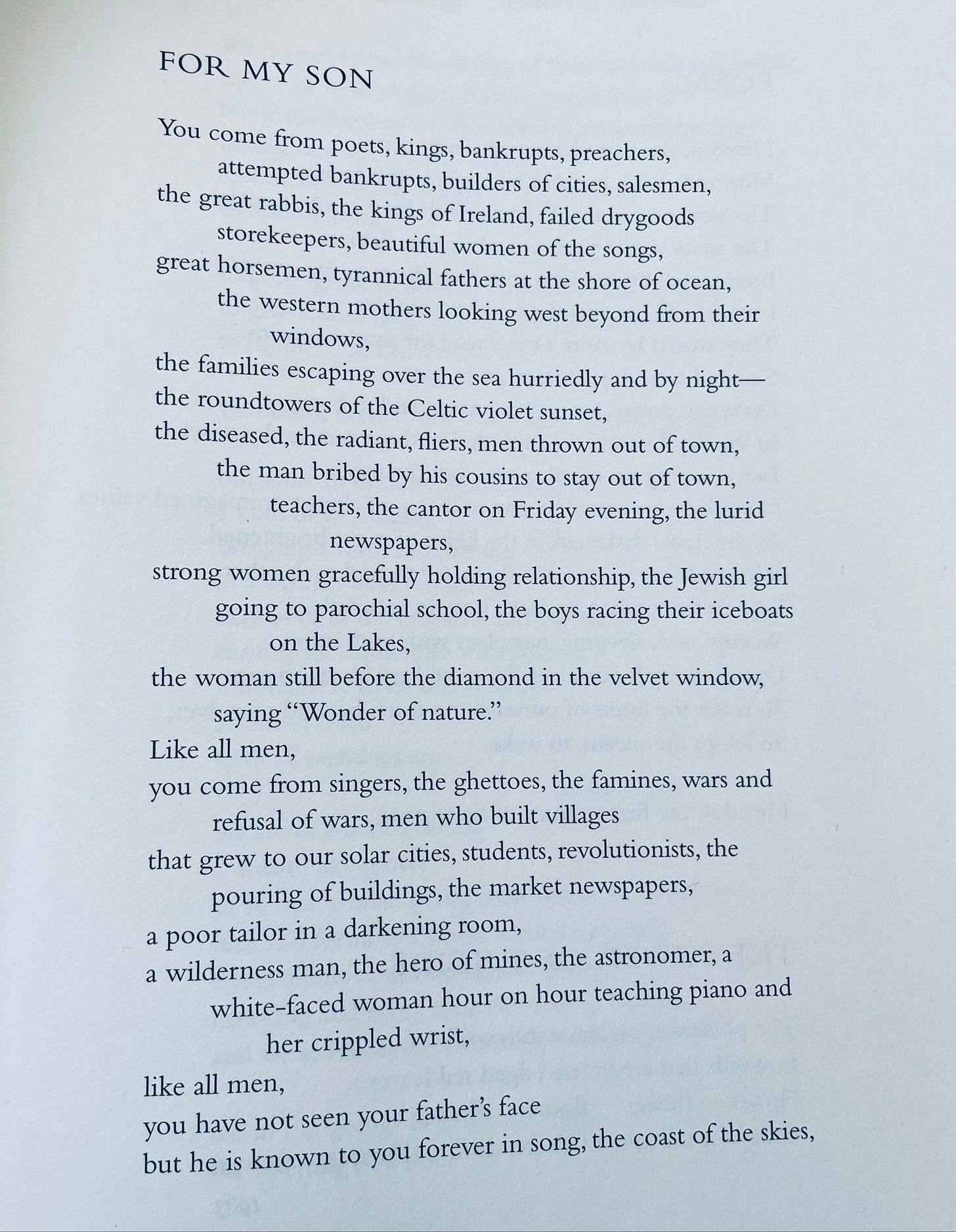

“For My Son,” a poem from the 1968 book The Speed of Darkness, is written from that future. At 55, she can see her son in his full ancestral relationship—to generations of kings, poets, rabbis, and storekeepers. Through that, she can see her own transformation.

Her transformation is visible in different way, when we consider the final poem and its draft. Rukeyser had been told in 1947 when she was pregnant that she could not both write and be a mother. Her gestures as she leaps from boat to boat show how she came to see her son as inheriting the line of human experience.

First, the final poem, and then the draft:

Her draft of the poem shows a handful of important changes:

Rukeyser changed “Hearst men” to “the lurid newspapers,” “Wall Street Journal” to “market newspapers,” and added “wherever you find man playing his part of father, father among our light, among our darkness.” She also added the line: “The woman still before the diamond in the velvet window, saying ‘Wonder of nature.’”

Rukeyser probably wanted the limiting qualifiers of “Hearst men” and “Wall Street Journal” gone, so that the poem would be more open to the idea of newspapers, which allows her to move into this complex and nuanced time- and place-shifting picture of nineteenth to twentieth century movements; of concepts of masculinity; of generations of family history. She restores to her son his place in his own lineage, that was robbed from him by his father’s absence.

The addition of the woman looking at the diamond, suggesting marriage, is a concise and lovely image that shows time progressing and the family line continuing. Including women in the list of the people behind the son’s existence makes them central to the historical trajectory.

In The Life of Poetry, Rukeyser articulates the relationship between working on one’s poems and working on one’s own life:

Rather than allude to the difficulties she experienced during the pregnancy, she gives us a poem that is an incantation. Her joy and attention to the mystery of a child’s development, is palpable and as fresh as tomorrow.

Plath’s “Brasília”

Like Rukeyser, Plath also wrote poems for her children. She wrote “Brasília” in 1962, for her son, Nicholas Hughes. Brasília is a designed city the middle of the Amazon, so it’s a terrific metaphor for her own experience becoming a parent.

The poem shows the dynamic of Plath’s personality, which was like a rope being pulled from both directions at once. She was at once a ruthless art monster, and an icon of 1950s domesticity. She possessed death and violence, but with an ecstatic tenderness.

In “Brasília”, this tenderness in rendered in tight tercets and painfully sharp images:

Her draft of “Brasília” shows some of her thought process as she revised this poem:

Plath omitted a first line, “Bone-splints of the future!”, choosing instead to begin not with a clarion call, but in the middle of a question. That question, “Will they occur”, doesn’t end with a question mark, but is a statement moving forward into the poem.

In the first line of the second stanza, she took out “great” before “masses”: great being a nothing word that adds nothing.

She changed line 8 from “Driven in, at the left, under my breast” to the direct and rhythmic “Driven, driven in.” She took out the passage from “I swim, old coelacanth,” to “And I, nearly extinct”: the fossil-like nature of the speaker is already implied by “bones.” She also omitted “or bad luck to the fishermen / Hairy and legendary” and instead moved right to “His three teeth cutting.” This choice eliminates anyone who is external to the action of the poem. The poem’s psychic distance moves much closer to intimacy.

The rest of the draft does not appear in the final version: “He is one of the new people / Motherless, fatherless. // The womb / Rattles its pod, the moon / Discharges itself from the tree with nowhere to go. // Are these eggs or amoebas, or zeroes, these notes / I see so constantly / Dying on the eyeless horizon / to be eaten by the mountain.”

This is asstounding to me. The lines Plath threw out are as good as those of any poem made this year, but she deleted them because they did not serve the poem. Plath’s willingness to part with images that most of us would be happy to preserve has a lesson for us. Poems are hard to write. It’s easy to get sucked into the Plath myth of her genius, but this draft shows her labour; going back again and again to get the language exactly right.

Dickinson’s “A Gale”

Emily Dickinson wrote the poem “A Gale,” in a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson in August 1877. It was published in 1891 after her death, re-titled “Storm,” in a version that altered her punctuation and other choices.

This is the poem as it was published in the Franklin edition, which restored Dickinson’s original intentions:

Her original drafts make her interior process visible. There are two versions in the database Emily Dickinson Archive, which I’ll call “Version A” and “Version B”.”

What I want to draw your attention to in this is the degree to which minor changes make significant impacts. In the Version A, the word “Streets” in line 1 was “Air” and the word “beryl” in line 7 was “opal.” There is an alternate word for “beryl” which is “bluest.” Dickinson also changed “in her . . . apron” to “in an . . . apron.”

Version A:

Version B:

I prefer “beryl” to “opal”. It connotes mineral more than jewel, but an opal better conveys the colors Dickinson was going for. I also prefer “Streets” to “Air” because there is a human element, something that goes beyond the pastoral. When I read this earlier version, I can feel the motions of Dickinson’s mind: Air to Streets, her to an, beryl to opal.

Temples in the jungle

The Magic 8 Ball of Poetry usually tells us to be as local and specific as possible. So it’s interesting to note that both Rukeyser and Plath changed specific nouns to more general ones. The power of a poem comes not only from specificity of diction, but from he effect of the person coming across into the page.

Looking into these drafts shows us two things: that even the best poems are part of a process of making an incision into the world; and that small changes can make a substantial difference.

I live in the Hudson River Valley. When I drive by hills and small mountains covered in trees, I sometimes imagine that they conceal pyramids, like the ones the Mayans built in the Yucatán Peninsula. The drafts that we normally leave unseen are like those temples.

We often think about writing drafts and getting to a finished poem as an action of erasing words and adding words, but the temples of language we’re building are a process of going into the consciousness, which is hidden from us under layers of dust, cobwebs, and detritus. Writing the drafts is the action of building the temple of this material; it’s buried under all this crap and we unbury it. Each crossing-out and marking-in is part of the poem coming out of the jungle.

For further reading:

Emily Dickinson’s Poems As She Preserved Them, ed. Cristanne Miller. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2016, p. 608. [Buy at Bookshop]

Lowell, Robert. Collected Poems. New York: FSG, 2003, p. 312-313. [Buy at Bookshop]

Mandelstam, Osip. The Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam, trans. W.S. Merwin and Clarence Brown. New York: NYRB, 1973, p. 105. [Buy at Bookshop]

Plath, Sylvia. Collected Poems of Sylvia Plath. New York: Turtleback Books, 2008, p. 258. [Buy at Bookshop]

Rukeyser, Muriel. The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005, p. 429-430. [Buy at Bookshop]

Rukeyser, Muriel. The Life of Poetry. Middletown, CT: Paris Press, 1979, p. 26. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

I appreciate this valuable craft lesson in essay form. Poets of all ilks will learn something here.

This was one of the most interesting and valuable posts about revisions I’ve read. Thank you!