This post is republished from February 20, 2021

People often seek out my Editorial Services for help putting the poems in a manuscript in the correct order. As with everything else involved making poems, the order of poems in a book requires careful thought and attention. It can be challenging for a writer to gain enough objectivity to do it themselves. I’m here to help.

Some poetry manuscripts display a narrative arc or are organized by a narrative chronology: the strategies of memoir can be applied to a book of poems. Other manuscripts might have sections that suggest discrete parts that work together. Other manuscripts are more impressionistic: the poems follow one another based on their emotional threads, or related subject matter.

When I’m presented with an unordered manuscript, still in its molten state, here’s what I do. I read the manuscript carefully multiple times. I spread each page on the floor (if you have the wall space, taping them to the wall also works well), then I list the beginning images and ending images of each poem. I then make an index in a spreadsheet with a code for each poem, so I can sort the poems by their beginning and ending images. Having such a database helps me to visualize the data, and notice the threads that form otherwise hidden connections. Once I have this data, I use a colored crayon to write numbers on each poem (not page) to show the new sequence. I try to link the ending image of one poem to the beginning image of the subsequent one.

I like the first poem in a book to be one that introduces most of the themes of the book; one that teaches the reader how to read the book. Many books of poems have recurring threads or images which can form a web of connections. Picture a detective’s wall with string connecting the clues:

In the early 1990s I heard Kurt Vonnegut give a talk at Indiana University. He made graphs to show the progression of stories in works of fiction. His method is also helpful when applied to ordering a book of poems.

Structuring it in this way gives more clarity to a manuscript; the skeleton can be thematic or emotional rather than progressing based on an x-y axis, where x moves from Beginning to Ending and y which has “ecstasy” at the top (plus sign) and “misery” at the bottom (minus sign).

In this example, Cinderella’s story begins close to the “misery” part of the y axis. She’s living as an indentured servant. The mice help her sew the clothes, then the ball is the highlight of her story, so it peaks near the “ecstasy” part of the y axis. Then midnight strikes and she goes back down to the same, awful life. But then the glass slipper fits and she lives with the Prince happily ever after (indicated by the infinity symbol).

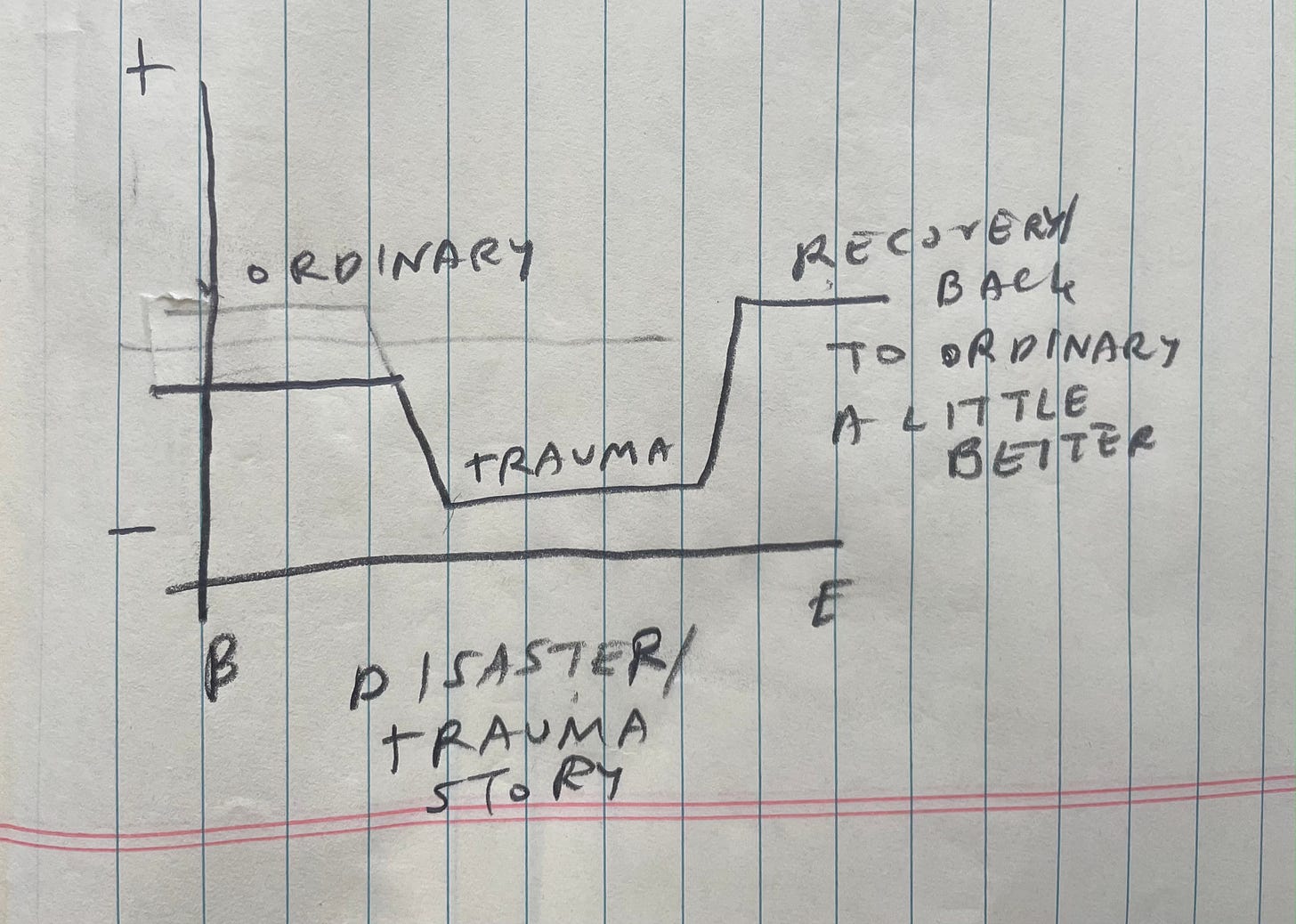

Example 2, a disaster or trauma manuscript

In this example, the speaker or character is living an ordinary life, somewhere in the middle of the y axis. Then some traumatic event occurs (girl falls in well, gets a disease, is chased by wolves, etc.). Then the story goes up with recovery to an ordinary life, but the character is doing a little better than before, so the line is higher on the y axis.

Example 3, The Metamorphosis

In this example, Gregor Samsa awakes from uneasy dreams to find himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect. He’s armor-plated and has a brown belly divided into stiff segments. However, he’s still in the same, ordinary life as before. He has to go to work, his family is driving him nuts, and nothing has effectively changed. He eventually dies and his corpse is pushed to one side of the room with a broomstick. It’s a flat line, with a drop-off at the end.

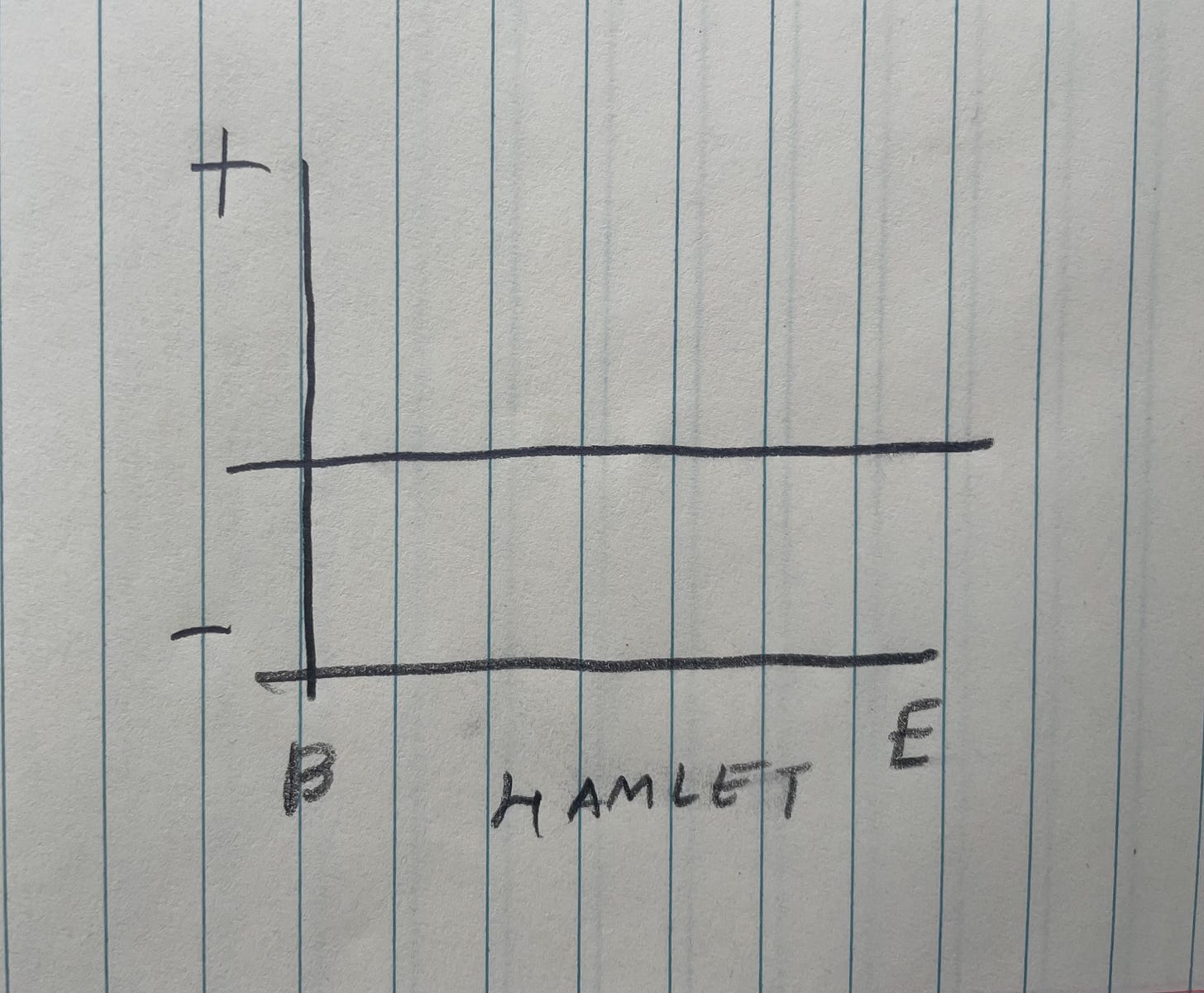

Example 4, Hamlet

In this example, Hamlet’s story is a flat line: the story is psychological, but Hamlet doesn’t change, learn, or do anything differently after the ghost’s visit in Act 1, Scene 4.

Thinking of the arc of a manuscript in this way can clarify the emotional direction of a book. Alternatively, manuscripts without a clear narrative can short-circuit this x-y axis dynamic to allow for more complexity and nuance. In other words, the book’s structure will mirror the content. A book’s architecture can reinscribe the subject matter: we perceive the speaker navigating their way through various inputs.

It can be helpful to imagine the book as one, big poem. Inside that poem are all the component poems: parts of the whole which serve as two-way mirrors,reflecting and communicating with the rest of the poems in the book.

Looking closely at classic books of poems, we can better understand what their architecture means and how it works.

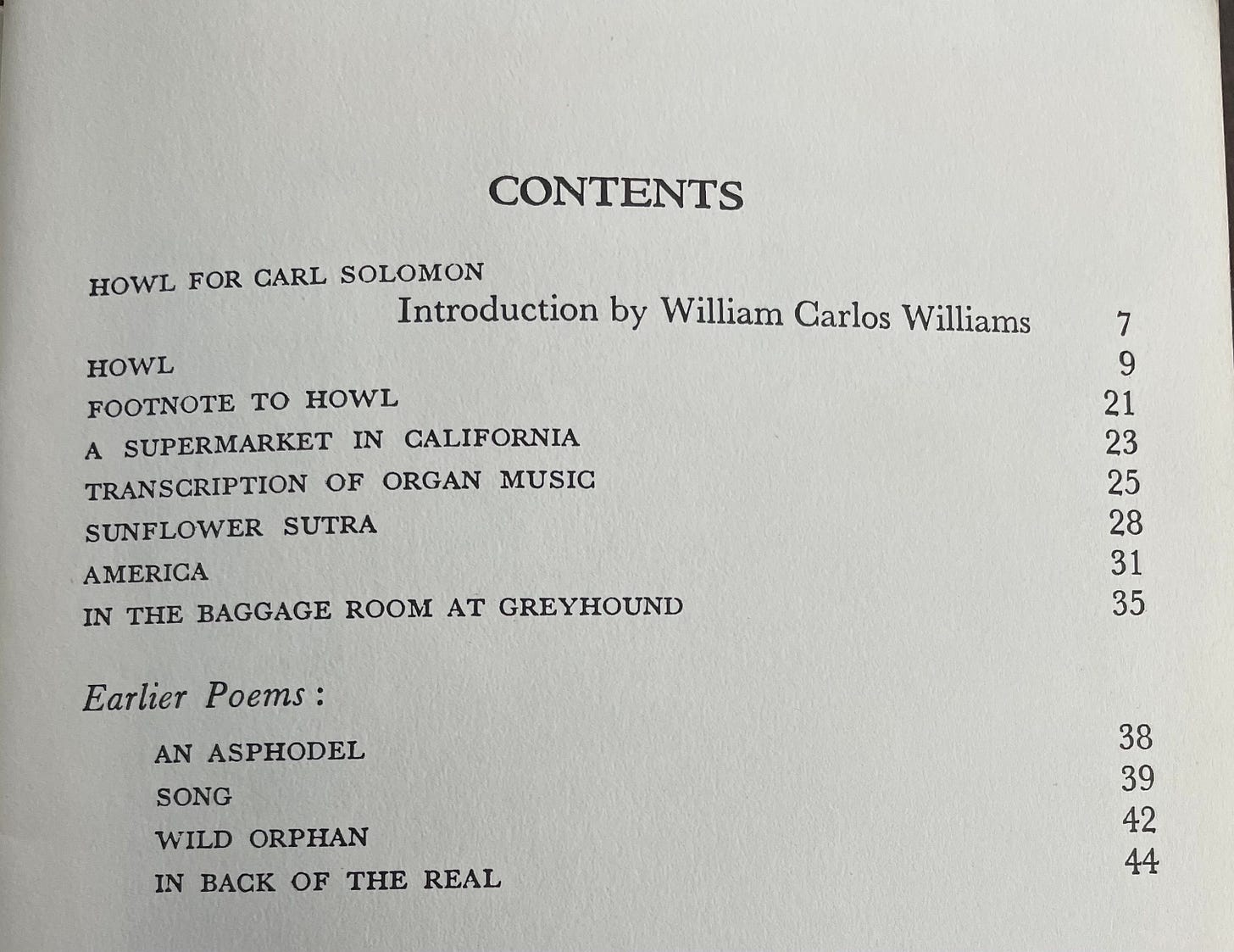

Howl

Allen Ginsberg’s Howl begins with its long title poem. This poem has an outsized life greater than the book itself, but there are other poems in the book. “Howl” is followed by “Supermarket in California,” and ends with a small, unremarkable poem, “In back of the real.”

The “Howl” sequence ends with the inauspicious lines “Farewell ye Greyhound where I suffered so much, / hurt my knee and scraped my hand and built my pectoral muscles big as vagina.” I defy anyone to read all of Ginsberg and take him seriously. He applied Whitman’s form to mid-20th century aesthetics, but he had little insight, and lines like that point to the extent to which he is overrated.

He front loaded the most significant poems, “Howl” and “America,” in the first half of the book, like a woody stem, but left the rest of it as fluff, like dandelion spores.

Ghost Money

Lynda Hull’s Ghost Money falls in three equally balanced sections with “Spell for the Manufacture & Use of a Magic Carpet” as a preamble.

“Spell for the Manufacture & Use of a Magic Carpet” ends with “the cities of New Jersey rising / white, small beyond the Palisades,” an image which comes up again and again in Hull’s poems. “Tide of Voices” begins in those cities, where “At the hour the streetlights come on, buildings / turn abstract.” This tide of voice, “pearling in our hands” leads to “Insect Life of Florida.” That poem’s final statement, “dangerous as the human heart,” leads to “The Fitting,” where the speaker as a young girl watches a seamstress sew a dress for her mother. Each poem continues in this way, where the absorption of the final image has aftereffects that lead directly into the next poem.

The poems in the second section become more personal, or psychologically intimate, with softer lights; the third becomes jazz-like, metaphoric, and metamorphic and ends with “Accretion,” which suggests the increasing, breathless, passionate syntax of the poem’s tiered tercets that are a single long sentence followed by a short sentence: “How small I am / beneath this vast sway.”

Hull was an absolute master of using lyric and narrative techniques with a highly wrought intensity to make her individual poems’ meanings infuse the power of the book as a whole. The order of the poems in Ghost Money are no exception; the structure is a kind of Charon that guides the reader along the streets—literal and figurative ones—until the self really becomes the language of her subject matter.

A self-described “feral child,” Hull was born in Newark on December 5, 1954 and died in a car crash on March 29, 1994. She attended Montclair High School and won a scholarship to Princeton in 1970, but dropped out of high school and ran away at fifteen. As a child, she was always writing or reading, drawing and painting. She was always interested in Newark. In 2009 I interviewed Hull’s mother, Christine Hull, who said: “We would go to Newark and Jersey City once a year around Christmas to deliver food to families in need... she just loved that. Her interest came about with the Newark fires... going to her grandmother’s roof and being totally impressed.” These early experiences come back again and again in her poems, but they are made mythological.

Magic City

Yusef Komunyakaa’s Magic City is a book about his childhood in semi-rural Bogalusa, Louisiana. Magic City has no sections. The book is thematic in the sense that it is about the legend of Komunyakaa’s childhood, and the poems move from one to the next in a inevitable way. Most (not all) the poems are in skinny, single-stanza forms that show his indebtedness to Surrealism and an effort to maximize surprise from line to line.

The book begins with the speaker as a five year-old and ends with him hearing people “telling each the secrets.” The next poem begins with a seven o’clock whistle, a kind of interruption of the quiet of the playhouse in “Venus’s-flytraps” underneath the floor where he overhears things he isn’t meant to hear; the whistle begins the morning and its sound is “a key to a door in the sky.” Each poem is en face with another that echoes its mate. For example, “Mismatched Shoes” ends with him choosing his Trinidadian grandfather’s surname, Komunyakaa, his “African fruit on my tongue.” This indication of speech leads into “My Father’s Love Letters,” which the speaker helps the father write. Though his father labors over a simple word, the letter is “redeemed by what he tried to say.” The book has a narrative arc that moves almost imperceptibly from childhood to adolescence to early adulthood. The book’s organic form arises out of the child’s intense psychological relationship to his surroundings. As the speaker changes, the book uses the emotional momentum of all the preceding poems to increase surprise and to show the development of the person—the speaker as much as the poet.

Guiding Principles

When I organize a manuscript, I try to keep in mind several guiding principles:

What is the most meaningful architecture that will signal the major threads of the book?

Do the threads of the book demand 0, 2, 3, or more sections?

If there are sections, how might they be balanced in terms of length and emotional weight?

Is there a narrative arc or some other overarching methodology?

How and in what ways does each poem connect or interact with the ones immediately around it?

How does the manuscript change or develop over its progression?

Does the speaker of the poems change from the beginning to end?

Does the first poem introduce the themes of the book and teach the reader how to read it?

Does the final poem end like a door or a window?

How does the energy in the book move—does it dissipate, open up, shut down, close, or summarize?

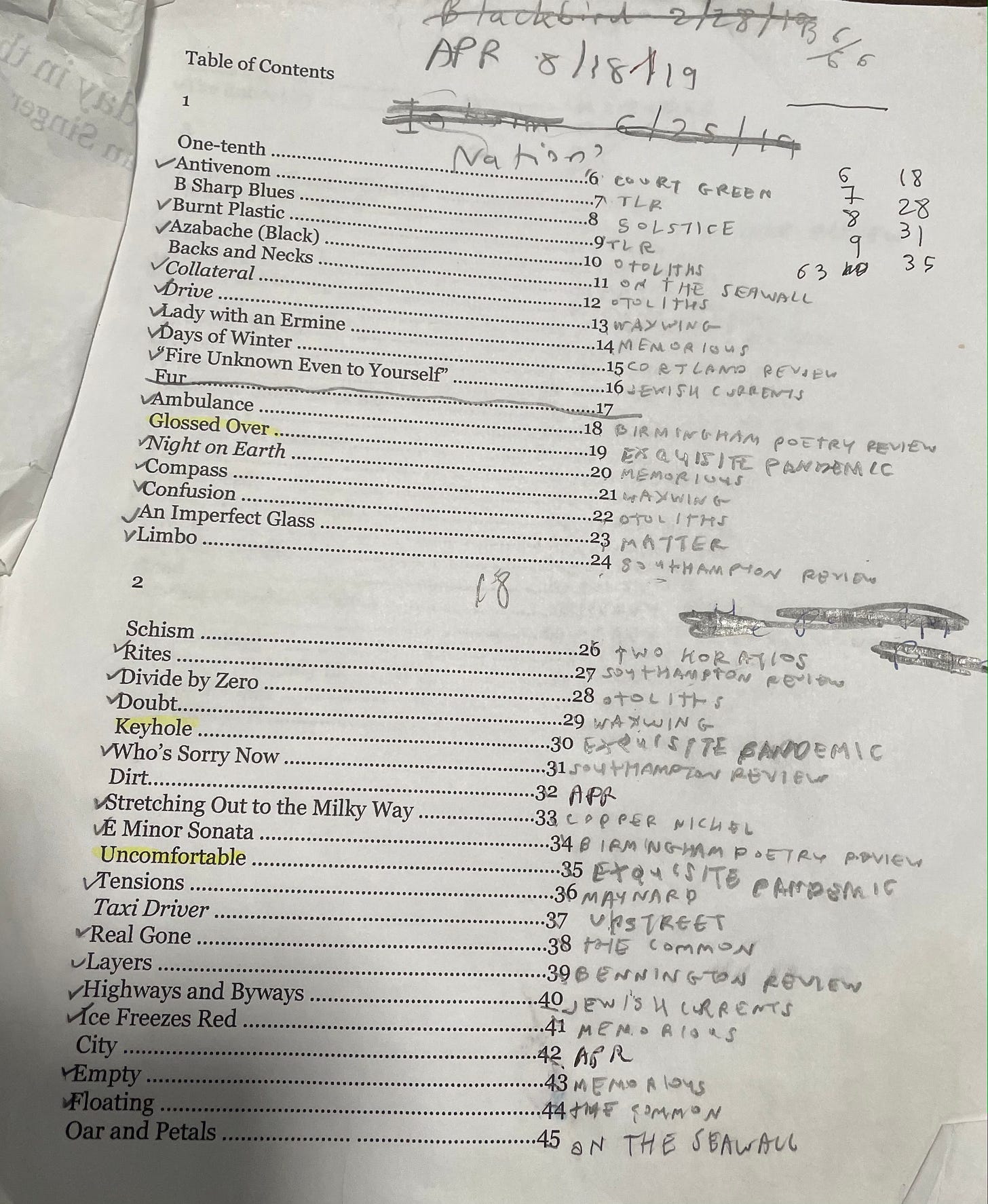

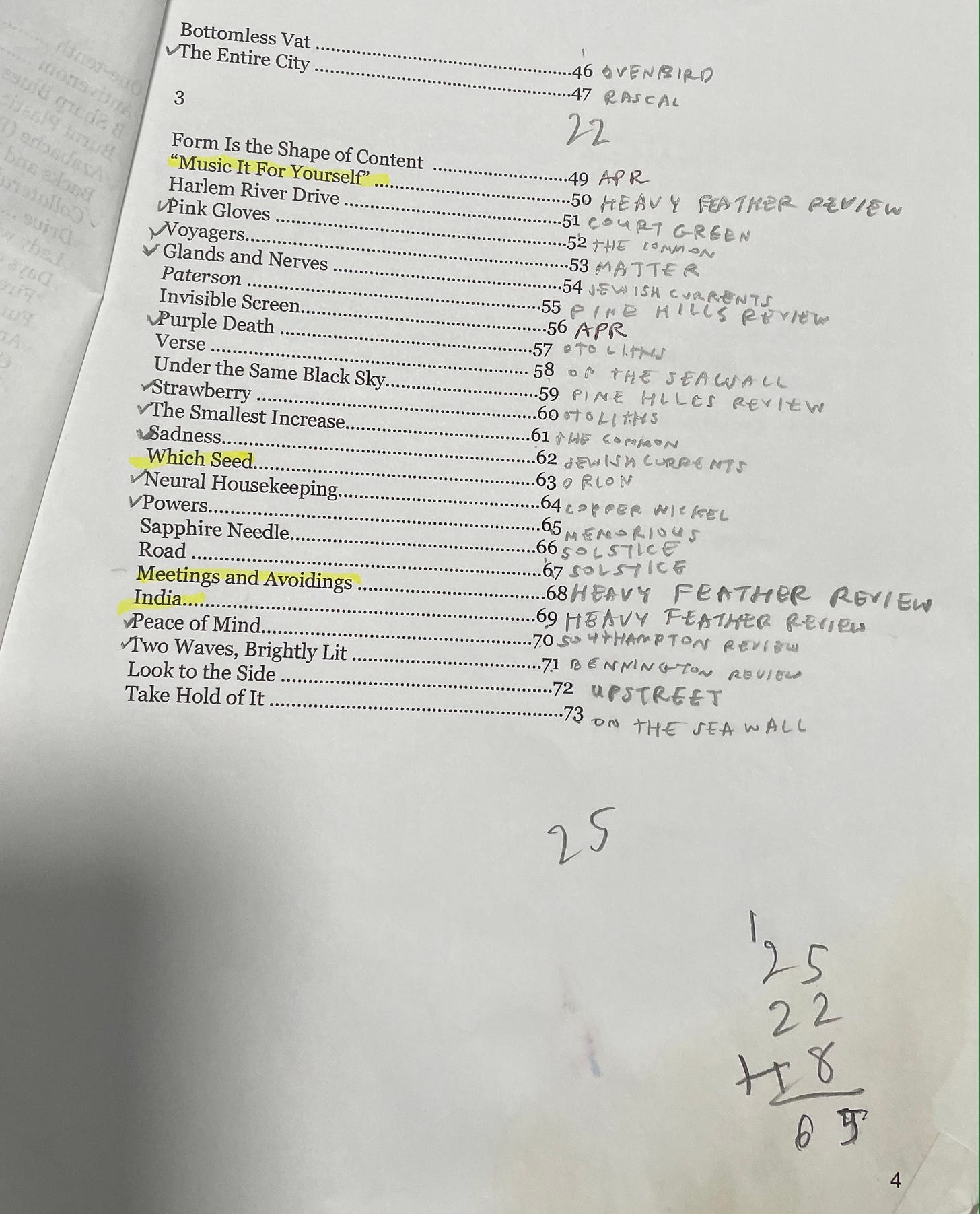

When I was organizing my forthcoming book, Today in the Taxi (Tupelo, 2022), I made three sections because all the prose poems in the book begin with a version of the phrase “today in the taxi.” Although the final poem begins “tomorrow in the taxi,” (since it looks forward rather than the past or past perfect) the three sections suggest the periodicity of morning, noon, and night. The book also has three “main characters” who appear as guides alongside the speaker/driver: Franz Kafka, Charles Mingus, and the Lord, who is a female voice.

The scribbles and math on the sheets show my attempts to balance the weights of each section more or less equally. I wrote the names of the magazines where the poems appeared to make the acknowledgements page easier to craft later on. I find most books too long, so there’s a good chance I’ll omit some of the poems before the book is published.

Ordering and organizing a manuscript of poems is a maximal version of organizing the structure of a poem. It involves the same attention to rhythm, pacing, form, and energy—only on a bigger scale. Applying the same principles used in the individual poems on the macro level is best done methodically; whatever vision you have for the book (the book you want to read, but does not yet exist) should be applied at all levels.

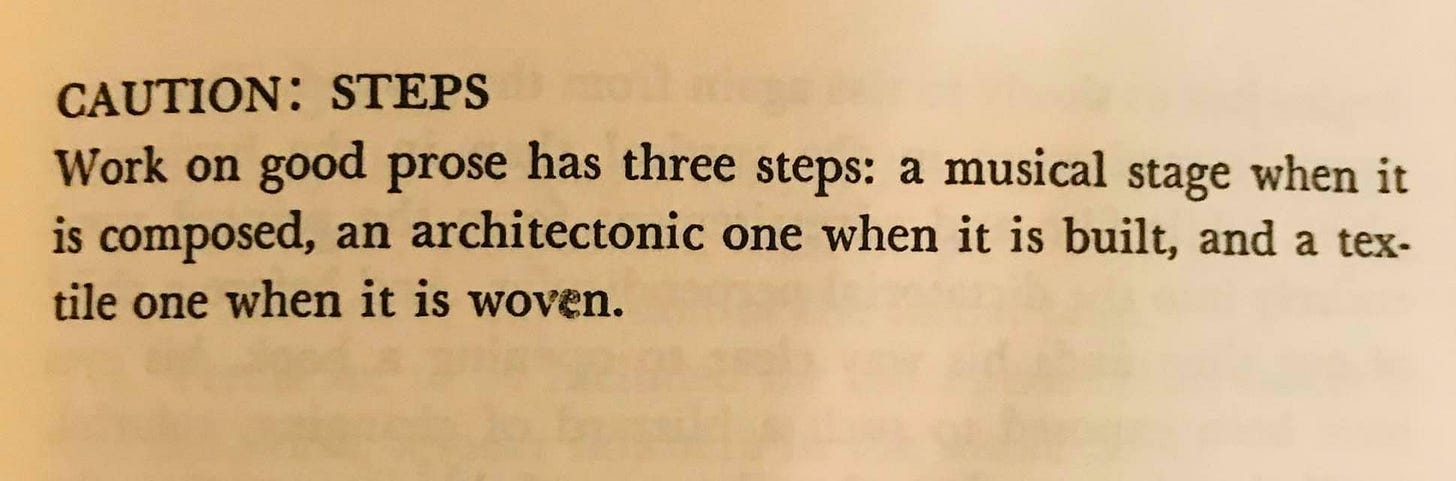

Walter Benjamin’s advice on good prose is applicable here:

Imagining your manuscript as a tapestry rather than a book will help your vision get clarity; each thread contributes to a satisfying whole that, when you stand back, shows the unicorn and the flowers around it.

About Sean Singer

Sean Singer Editorial Services

For further reading:

Benjamin, Walter. Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. New York: Schocken, 1978, p. 77. [Buy at Bookshop]

Ginsberg, Allen. Howl and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights, 1959. [Buy at Bookshop]

Hull, Lynda. Ghost Money. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1986. [Buy at Bookshop]

Komunyakaa, Yusef. Magic City. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1992. [Buy at Bookshop]

As I hope/plan to organize a poetry manuscript this year, this post is immensely helpful. I especially like the suggestion to flag opening and closing images throughout poems to discern connections and thematic throughlines. Also, it's very helpful to think of the manuscript as a tapestry, rather than a book. I will bookmark this post, thank you!!

Thank you for this insightful and helpful article on how to organize a manuscript. I found your tips and examples very useful and inspiring. I especially liked how you explained the difference between a collection and a book, and how to create a narrative arc and a thematic coherence. This is exactly the kind of lecture I wanted at the Elk River Writers Conference. I hope to that you offer these type of craft lectures in future workshops.