Craft: Kenneth Patchen

This craft piece was suggested by Tracey Knapp. If you have a suggestion for a topic, please suggest one here:

Kenneth Patchen (1911-1972) was an American original. He moved through poetry in the most catholic and fluid sense, applying his idiosyncratic sensibilities to verse, “picture-poems,” and allegorical prose. He experimented with poetry-jazz combinations, and embodied the anti-cool, anti-Beat figure—socially conscious, endlessly inventive, and full of compassionate imagination.

His titles show a mind not beholden to what anyone else in poetry is or was doing: The Teeth of the Lion (1942), An Astonished Eye Looks Out of the Air (1945), The Famous Boating Party (1954), Hurrah for Anything (1957). If William Blake was a 20th century instead of an 18th century figure, he would have been Kenneth Patchen. Both Blake and Patchen produced compositionally similar tapestries that combined their imaginative capacities for image and text.

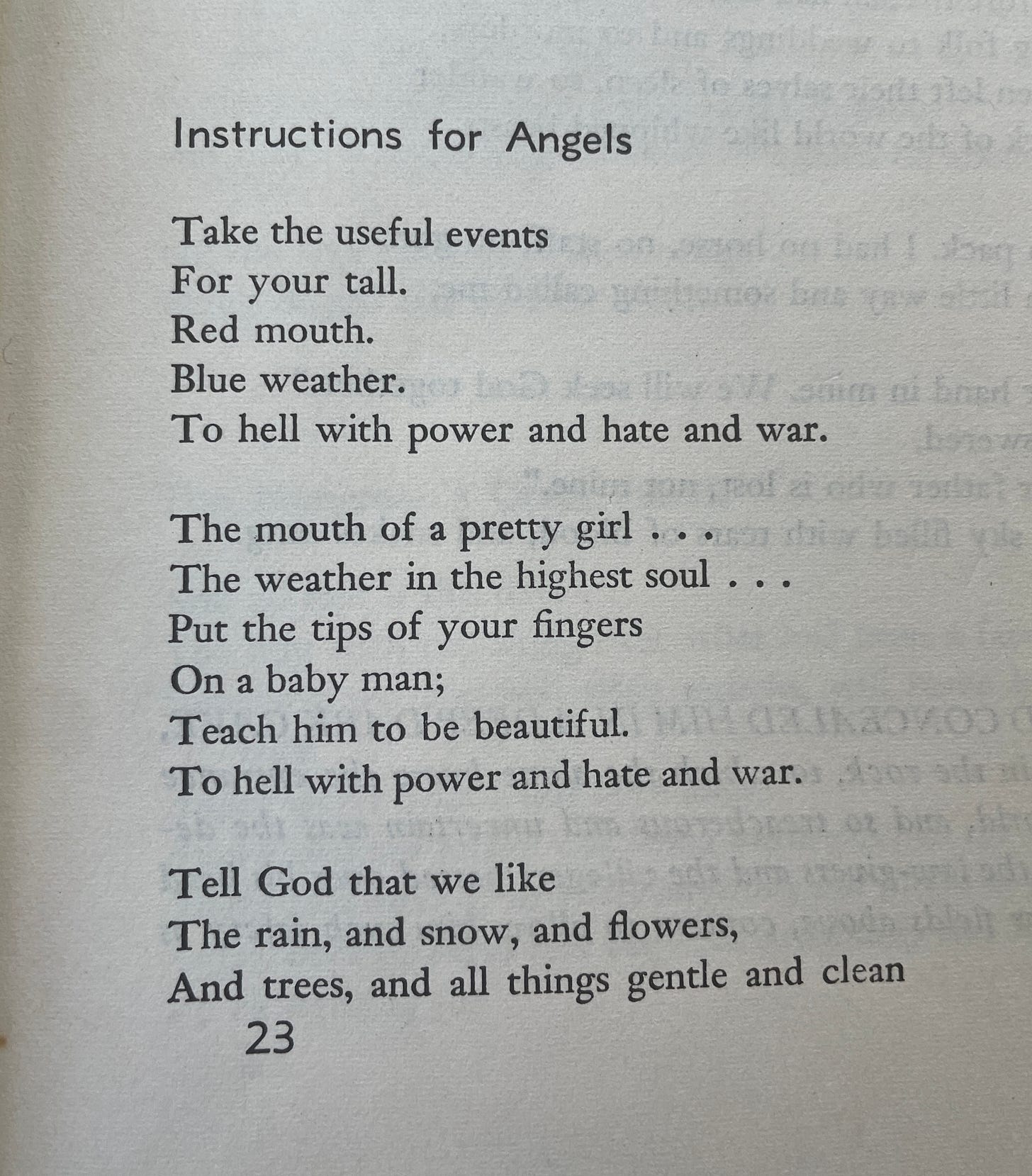

Patchen’s primary concerns were preserving the imagination amid a world of unrelenting violence, maintain child-like wonder, making life into legend, and worshipping romantic love beside an awareness of God’s presence in all things.

Patchen’s poems always sustain a general affection for the universe. “‘The Snow is Deep on the Ground’” includes many of the threads that his poems present. In 1937, when he was 25, Patchen suffered a permanent spinal injury while trying to fix a car. In 1956, following his second spinal fusion operation, he said it: “gave me relief and mobility (& for the first time) I was able to go about giving readings, and so on.” Then, during a subsequent operation, Patchen suffered another slipped disc while under anesthesia. In 1963, believing he was somehow dropped during the operation, he sued his doctor for malpractice, but lost.

Despite this, Patchen produced more than 50 volumes of poetry and prose and made hundreds of picture-poems.

In 1950, T.S. Eliot (who hated Patchen’s poetry) organized a benefit reading to raise money for Patchen’s medical bills. Thornton Wilder, W.H. Auden, Archibald MacLeish, e.e. cummings, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, and Edith Sitwell attended.

In addition to the debilitating physical pain he had for the rest of his life, Patchen also constantly struggled to earn a living. He worked in steel mills to earn money for college, and his wife Miriam had a full-time job selling perfume in a department store. In 1967 he received a $10,000 grant from the NEA.

Patchen, if people know anything about him, was a devoted pacifist, even opposing American involvement in World War II, of which he said: “I speak for a generation born in one war and doomed to die in another.” His pacifism informed much of his thinking, and was the basis of his friendship with Kenneth Rexroth (though Patchen’s closest friend was Henry Miller).

Patchen’s discursive imagination led him to other expressions than lyric poetry, especially jazz and visual art. This recording with the Chamber Jazz Sextet (The Chamber Jazz Sextet included Modesto Briseno on tenor and baritone saxophone, Frank Neal on alto saxophone and bass clarinet, Robert Wilson on trumpet and percussion, Fred Dutton on bass and bassoon, and Tom Reynolds on drums and tympani) was booked in California with the Art Pepper Quartet. After being hugely popular, they were then double booked with Dave Brubeck’s Quartet. Patchen and the Sextet performed Tuesdays through Thursdays, and Brubeck’s Quartet did the weekends.

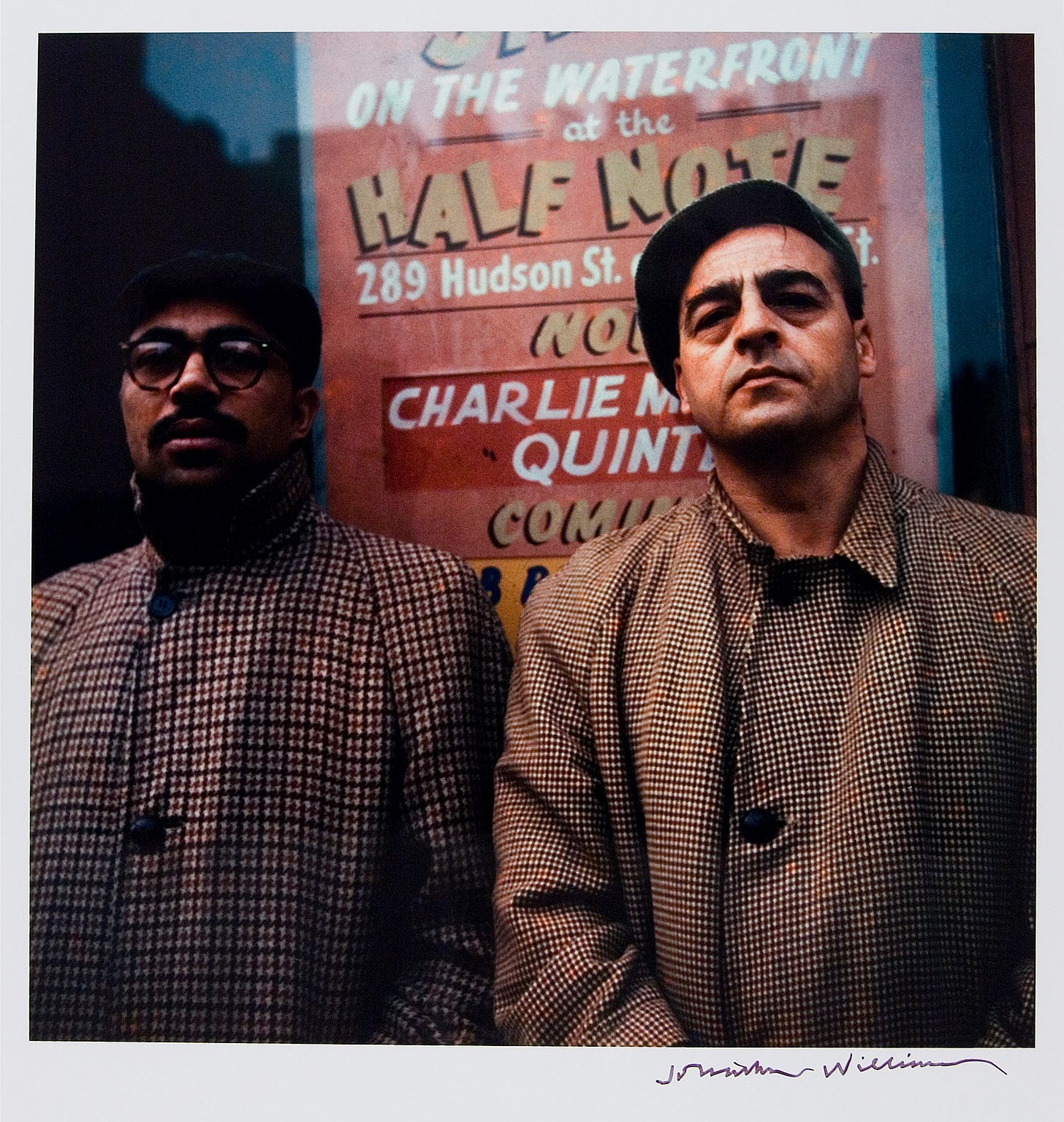

Patchen’s interest in jazz was not unique to Patchen, but the high level at which he attempted combining presentations of jazz with poetry is unusual. For example, he performed (though no recording exists) with Charles Mingus.

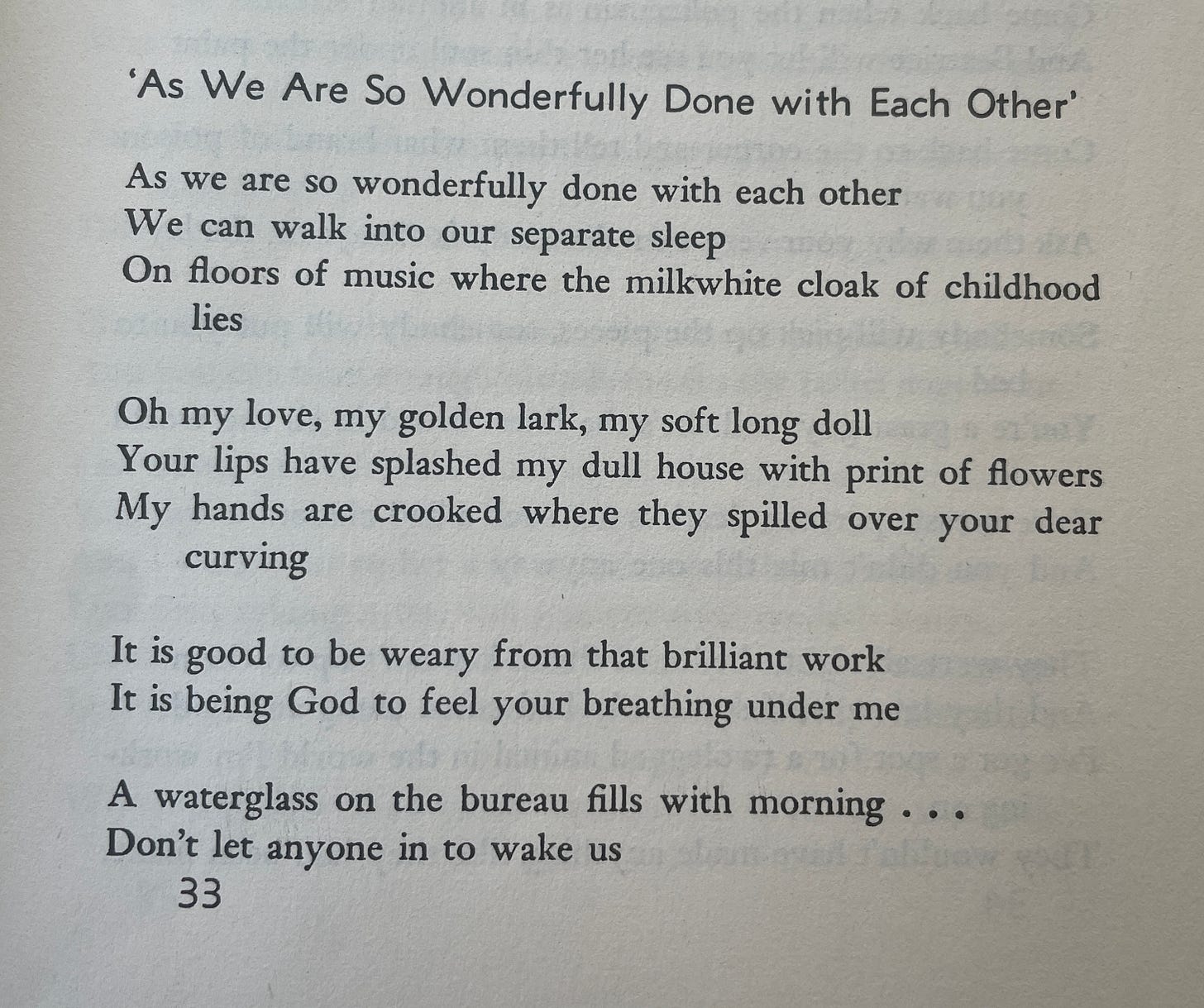

Patchen’s love poems are still tender and interesting without being sentimental or misogynistic as some poems by his contemporaries might be.

“‘As We Are So Wonderfully Done with Each Other’” evokes the potential for romantic sex to allow partners to enter into other dimensions. The poem is set immediately after exiting the dimension; the interrupted thoughts and enjambments reflect the immediacy of an embodied moment as well as more expressionistic musings.

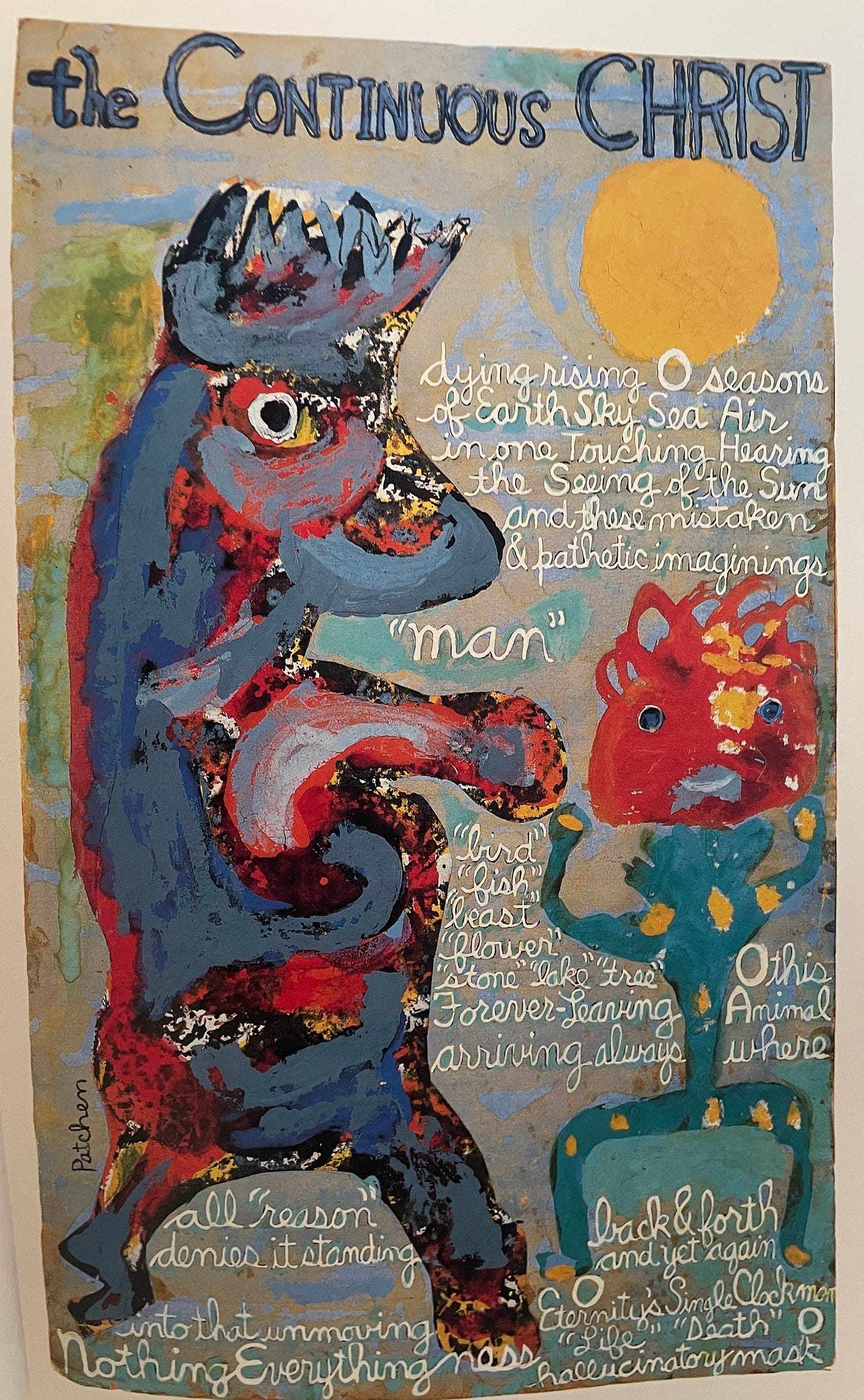

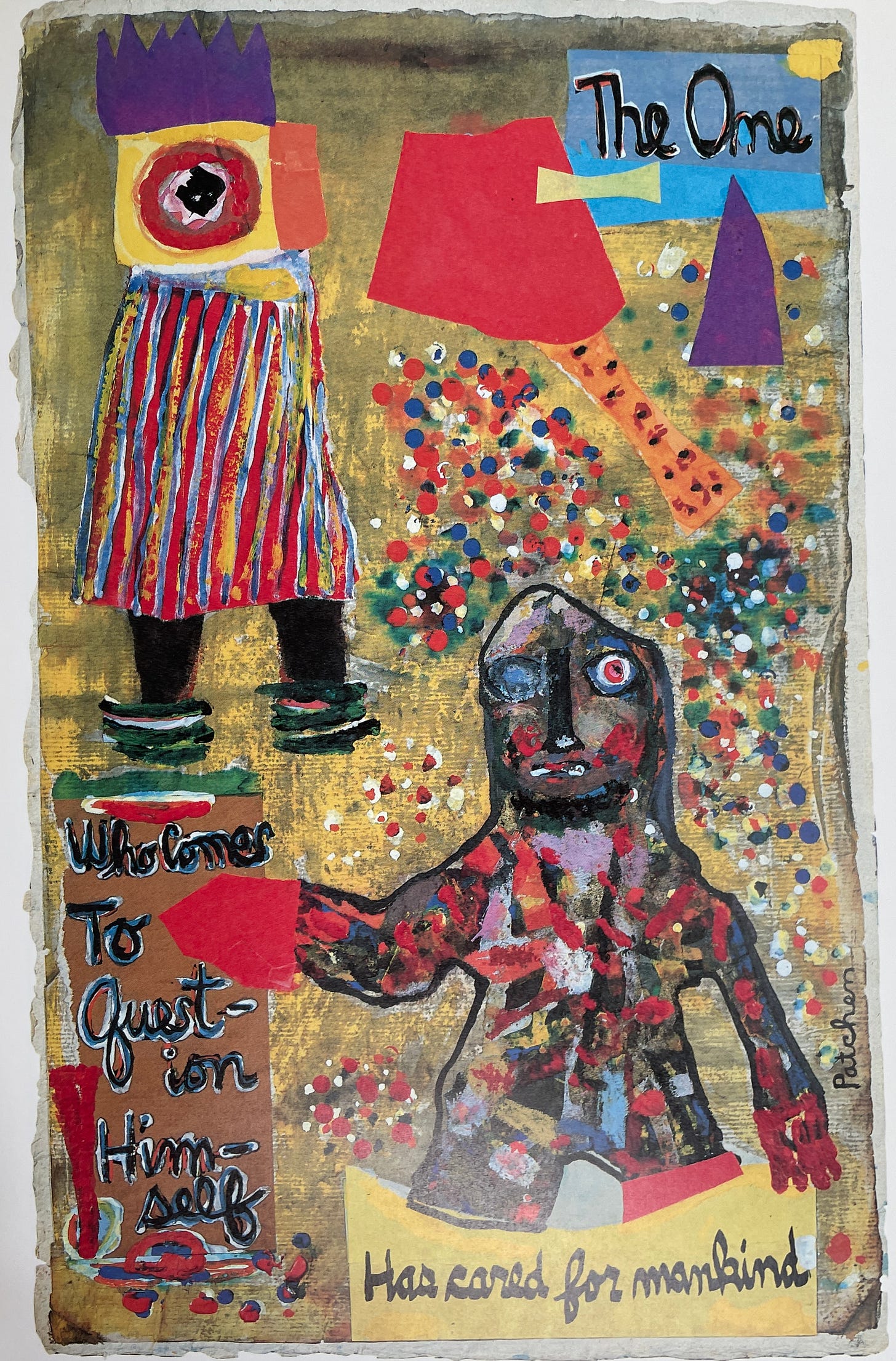

Patchen’s “picture-poems” used a variety of media: tempera, watercolors, inks, glues, dues, cloth, crayon, yarn, and construction paper. His pictures live as both folk and sophisticated, improvised and deliberate.

The painting is similar to the CoBrA artists from 1948-1951 who took their name from the cities Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam where they were from. Patchen’s cartoonish figures are neither fish nor fowl. They retain mythical properties and have an anxious, folkloric decoration.

Here, too, a king-like donkey overlooks a companion figure, a tomato-lizard in regalia. Patchen’s animism (“‘bird’ ‘fish’ ‘beast’ ‘flower’ ‘stone’ ‘lake’ ‘tree’ Forever-Leaving arriving always O this Animal where all ‘reason’ denies it standing”) is evident in the text as well as the picture. Of this relationship, Patchen said:

I have in the last, oh fifteen years, as you know, done a great deal of graphic work, and it happens that very often my writing with pen is interrupted by my writing with brush, but I think of both as writing. In other words, I don't consider myself to be a painter. I think of myself as someone who has used the medium of painting in an attempt to extend. It gives an extra dimension to the medium of words.

Patchen’s ethos of pacifism extended to his personal choices and his claims for art. Patchen described his work as “the region of magic, the place of the priestly interpreter of nature, the man who identifies himself with all things and with all beings, and who suffers and exalts with all of these.”

His 1941 novel The Journal of Albion Moonlight is difficult to characterize. The book includes diaries, lists, fragments, drawings, outlines, and prose; the setting is the beginning of World War II: Hitler, genocide, violence, war, and God are all woven through these variety forms.

When James Laughlin, the publisher of New Directions, was baffled by the book, he sent the manuscript to Edmund Wilson for an appraisal. Wilson’s response:

It is a mixture of Rimbaud, the Dadaists, Kafka and a number of other things—with a considerable talent of Patchen’s own improvising a rigmarole of images, ideas and dialogues. I haven’t found it exactly boring to read: there is a lot of verbal felicity, and there are are many unexpected and amusing things…he has talent and he ought to be encouraged; but he is still pretty juvenile. I skipped large sections of the latter part of the book, so you need only pay me $40.

Because Patchen was so prolific (his Collected Poems is nearly 500 pages) it is hard to give a comprehensive look into his range and capacity.

His poetry is serious and sincere, but at the same time playful, humorous, and has a bardic or druidic sensibility that people now would mostly be too cool for. Patchen may be uncool, but his work has a gooey core of sincerity that can’t be imitated.

For further reading:

Patchen, Kenneth. Collected Poems. New York: New Directions, 1969. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

“a gooey core of sincerity”! I like that.

Sean, please consider featuring Jane Mead’s work in a future Saturday post. Her poems deserve to be read, felt, and thought about.

Thanks for this post on Patchen, which I’ll read today.