October 23, 1956, two days after Juan Ramón Jiménez won the Nobel Prize for Literature, his wife, Zenobia Camprubí, died of ovarian cancer. We can never revise our lives, but revision opens the possibility to improve any piece of writing.

Revision is perfect and imperfect, so it is a manifestation of larger questions. Creation is the seed, and correction is its counterpoint, the pruning. In 1931, he explained:

Purity and perfection are never far from poetry’s bedside. If unfinished poems are abandoned, is it done with remorse, boredom, resentment, or desperation?

The idea of revision is the reenactment of the generative process—the draft may be dark, but the revision seeks clarity.

Aphorisms and insights

Jiménez’s insights show us new ways to think about reflecting on correcting:

Surprise your work

Imagine you are looking at a poem by someone else; detachment from subjectivity will put space between the poet and the poem. Imagine sneaking up on it in an alley with a bar of soap wrapped in a shirt.

Artificially creating psychological distance is the first important step in revision. Often, I want the poem is be something I would arrive at after prolonged concentration, but the pressure to put it into form can’t short-circuit my own limitations having not given it prolonged concentration. This is the bind.

Being too close to the poem means that you probably can’t take pleasure in it, either. It is not possible to be the sensitive reader you seek in the world. If you see your poem at arm’s length, it could change your attitude towards it.

Revise part of your work, but remember the whole

Jiménez was known for revising his poems over and over, even after they appear in print. He believed that he was not just revising a single poem, but his Work, which was tantamount to his entire life.

For him, each poem was a fragment of a draft of the life, so any revision was an attempt to detect and repair minutia and nuances. Conceiving of the entire corpus of poems—drafts, poems, books—is a more expansive understanding of revision as a learning process. Finding a balance between “revising with no end” and “revising as being sufficient” only comes with practice and patience.

Correction is sometimes only confirmation

Of all Jiménez’s ideas about revision, this is his most abstract, but also most significant. Revision is typically thought of as crossing out a word in favor of a more muscular, accurate, or specific word, tinkering with punctuation, or breaking lines into different lengths.

Jiménez believed that it was not always necessary to change anything in the text, but to reimagine it, to “confirm it and to hear its confession.” A poem is a juncture between solitude and communion. It is also a document of the deepest part of yourself—that wilderness that cannot be explained or understood any other way.

A poem that is “working” will transmit the energy the poet initially instilled in it.

Respect the person you were

This is one the most challenging aspects of revision. If we begin with the premise that poetry is about transformation of the self, as Stanley Kunitz said, “to convert the life into legend,” then it would follow that the person revising is fundamental not the same as the person who wrote the poem.

Asking forgiveness and maintaining affection for the person you were when you wrote that piece of junk is often done hastily without contemplation. The poem in its molten, imperfect state is telling you something. No one does anything for no reason. Poets especially choose their words deliberately and purposefully. If the poet then put it down that way, there was a reason for doing so.

Poems begin with listening, and listening to who you were when the draft was made can guide not only revision, but the coming life.

Respect the defect that cannot be conquered

Anyone who has been in a long-term relationship knows that people’s character does not or cannot change. Since poems come from the part of the self that the person wrestles with, and does not understand, the “errors” or “defects” in the poem being revised might have to remain that way.

Making this limitation into a useful energy could be the real secret of revision. Embracing it as an element that can be questioned in future poems is the best possible result of any focus on revision.

Take down the scaffolding

Revision is about making the poem seem effortless, as if it took no time at all. It should seem both spontaneous and inevitable. Reclaiming and protecting this spontaneity means surprising the reader, and surprising the reader means surprising oneself.

I Am Not I

One of Jiménez’s poems, “I Am Not I” (trans. from Spanish by Robert Bly) expresses the essential position of the poet—they are person becoming the person who will write the poems:

Revision is misunderstood because it is seen as something that happens after the writing has taken place, but what if it was merely another step before the next poem? What if, instead of tinkering, it was an exercise in understand who we were on the way to who we will become?

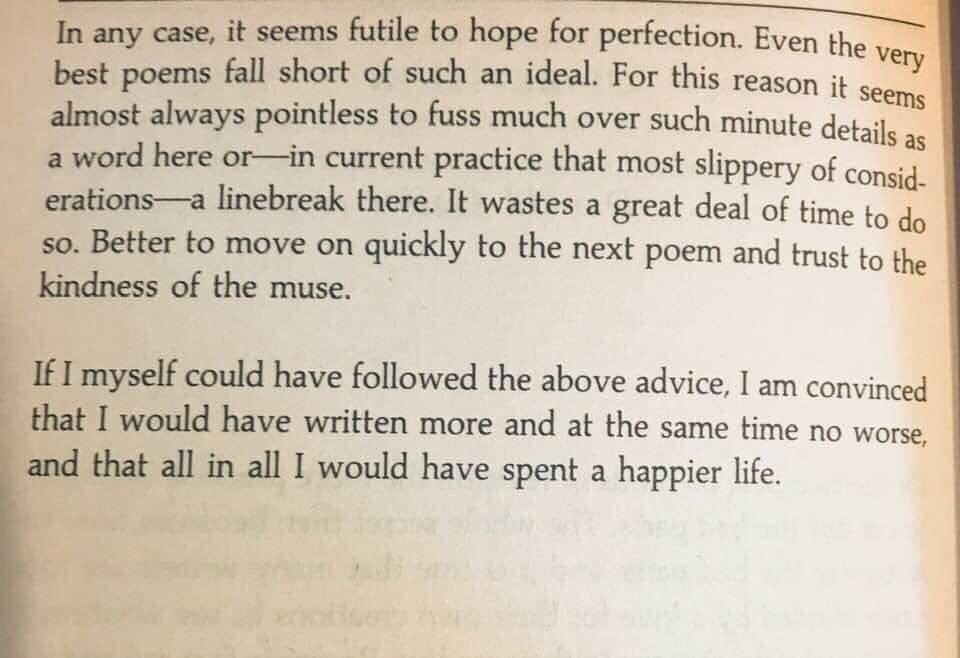

Futile to hope for perfection

Donald Justice represented a somewhat different view on revision. Rather than seeking perfection, he thought it better to move on quickly to whatever was coming next:

Rather than putting so much emphasis into revision, it is sometimes better to just move on. But what does Justice mean by “the kindness of the muse”?

There were nine muses, and they were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne. The root of the Greek word μούσα means “to put in mind” or “have in mind.” “Museum” literally means “place of the muses.”

This suggests that the muses are already within us, and the external muses we have (whether they’re people or places) simply invoke that dormant part of us.

To re-see

Yusef Komunyakaa said “revision literally means to re-see.” The severest test of the imagination is to re-see anything. This becomes particularly challenging when the object is our own poem.

Any method you can come up with to increase objectivity and decrease subjectivity is useful: turning the poem upside-down, reading it from the end to the beginning, cutting the stanzas out with scissors and rearrange them, writing them in longhand, reading them out loud, pretending you are not yourself but a character named Crazy Moondog, and cutting all exposition are some things to try.

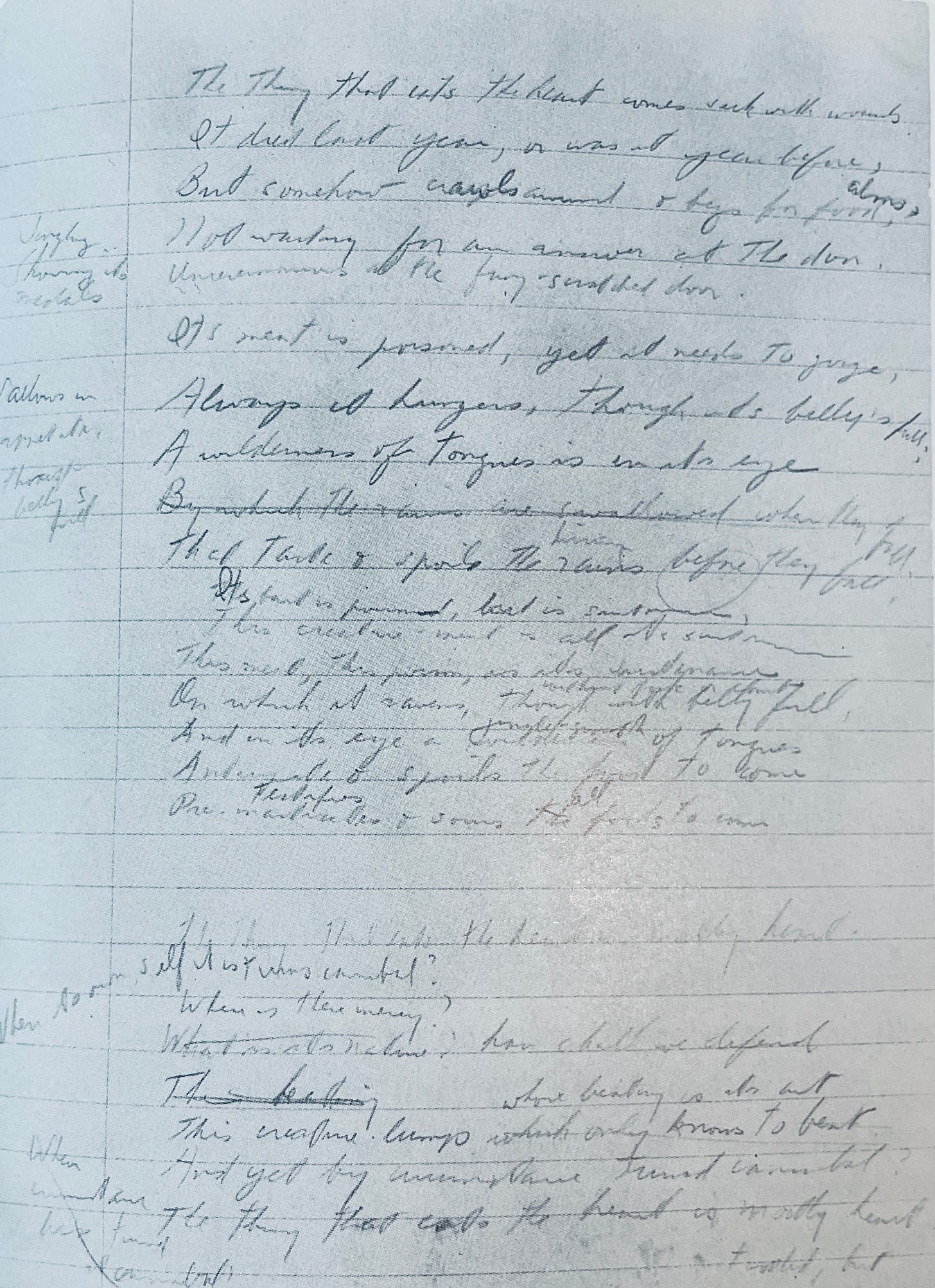

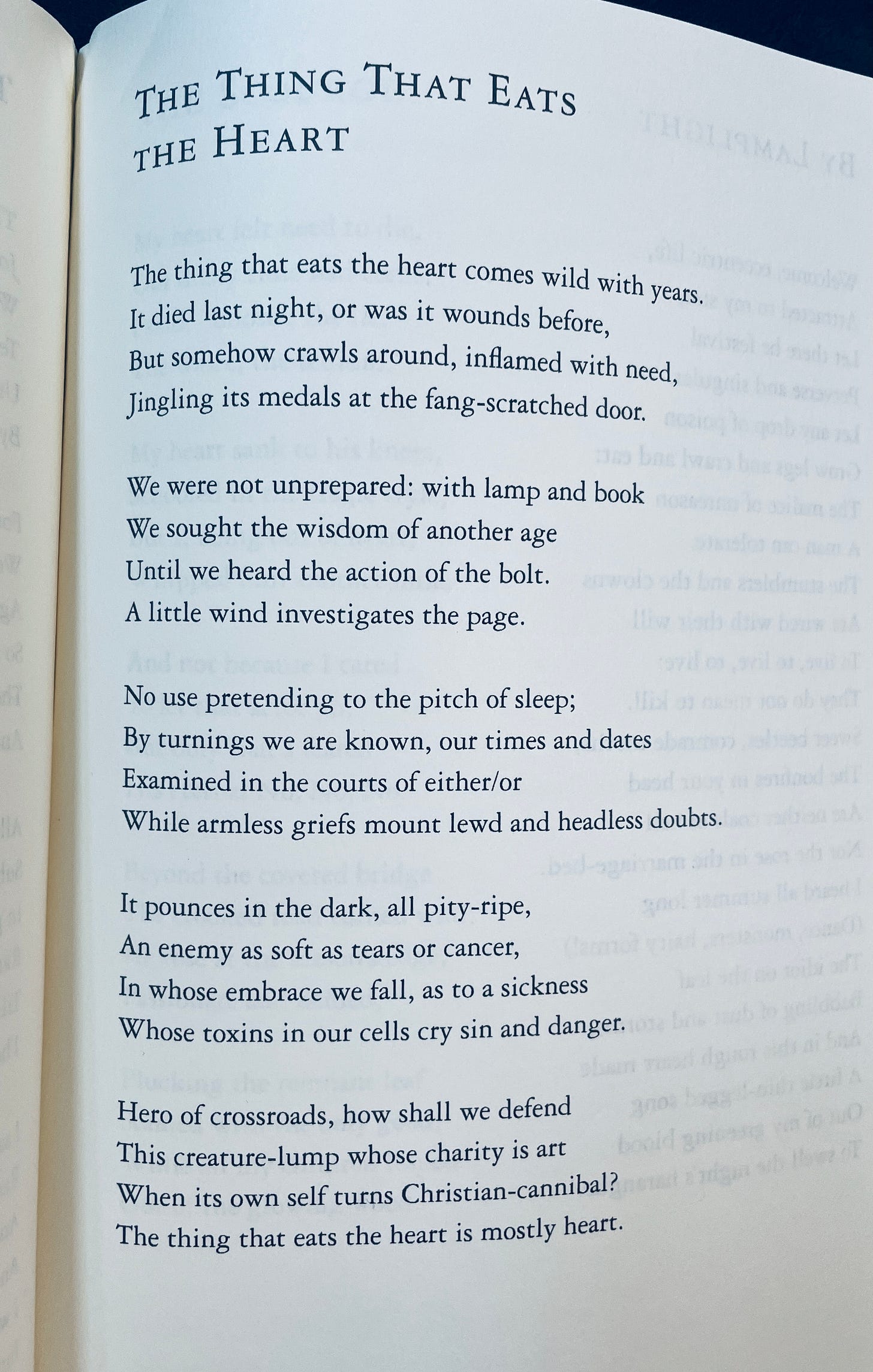

The Thing That Eats the Heart

The draft of Stanley Kunitz’s poem “The Thing That Eats the Heart” shows many lines he rejected in the final version, such as “Always it lingers, though its belly’s full; / A wilderness of tongues is in its eye.” His draft is almost a completely different poem:

Poems are a holy thing. Revision’s goal is to maintain the poem’s aura—its position in space and time—while making it clearer. Clarity demands the rational mind; the spark of generation demands the emotional mind. Revision is a combination of the two, the wise mind.

Whether wooing or trembling, our physiognomy changes into alien terrain, our feelers and tubular siphons reel into the dark which is the unknown. Human skin is not unlike the honeyed mind and the living bones—it seeks patterns and is image-making.

In finding the ultimate shape, we must consider all materials from nature: the marine shell, onyx, ginger, lava, wet cliffs, and the layers of geologic Scripture. Poems consciously re-inscribe our consecration of the Earth, the blowing ram’s horn into lime and orange air.

Revision has the rigor of confession and an admission that poems do not always begin in wisdom, and they may end in only a quiet murmuring. Joining light and flesh is the joining of perfect and imperfect. Re-seeing the poem is a gift, the way the lichen and the oaks are: a direct relationship of our ongoing invigoration and our decay.

For further reading:

Jiménez, Juan Ramón. The Complete Perfectionist: A Poetics of Work, ed. and trans. by Christopher Maurer. New York: Doubleday, 1990, p.160-161. [Buy at Bookshop]

Justice, Donald. “Of Revision,” The Practice of Poetry, eds. Robin Behn and Chase Twichell. New York: Harper Perennial, 1992, p. 250. [Buy at Bookshop]

Kunitz, Stanley. The Collected Poems. New York: Norton, 2000, p. 115. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

Wonderful lessons here - thank you! A teacher once told me a section of a story was "overwrought" - I thought he meant messy, or too emotional, and attempted to revise again; he actually meant over-wrought as in too crafted & not emotional enough. It's something I always think about when revising.

I have some great advice for anyone that wants to make something perfect--make it out of something besides words. Seeking "perfection" in poetry is too often--consciously or otherwise--seeking proscription...