The English poet Rosemary Tonks (1928-2014) is overlooked, underrated, and undervalued, but why? Part of the reason is that women poets in the 1960s were mostly ignored; another is that at the peak of her poetic abilities, she gave up writing altogether and disappeared.

Hers is a world of edged, risky complaint. Her poems are about failures, errors in judgment, and dissatisfaction. So dissatisfied, in fact, she abandoned poetry altogether in the 1970s, and disappeared at the height of her powers. She only published two books of poetry in her lifetime: Notes on Cafés and Bedrooms in 1963 and Iliad of Broken Sentences in 1967.

Tonks was a knot of paradoxes: she sought communion with readers, but pushed into total solitude; she was Rosemary Tonks the master of heightened senses and sensibilities and the Christian convert Rosemary Lightband living by the seaside with minimal possessions and no contact whatsoever with the literary world; she achieved what she called the “main duty of the poet…to excite—to send the senses reeling.” Her poems are not well-mannered, or decorous; they’re hedonistic, visionary, the voice of the drama of the ordinary.

Tonks’s poetry is contemptuous of self, of the image of the self, and the way others see the self. Entering her poems is really like moving in her mind, to witness her control her chaos, becoming more like her language than anything else.

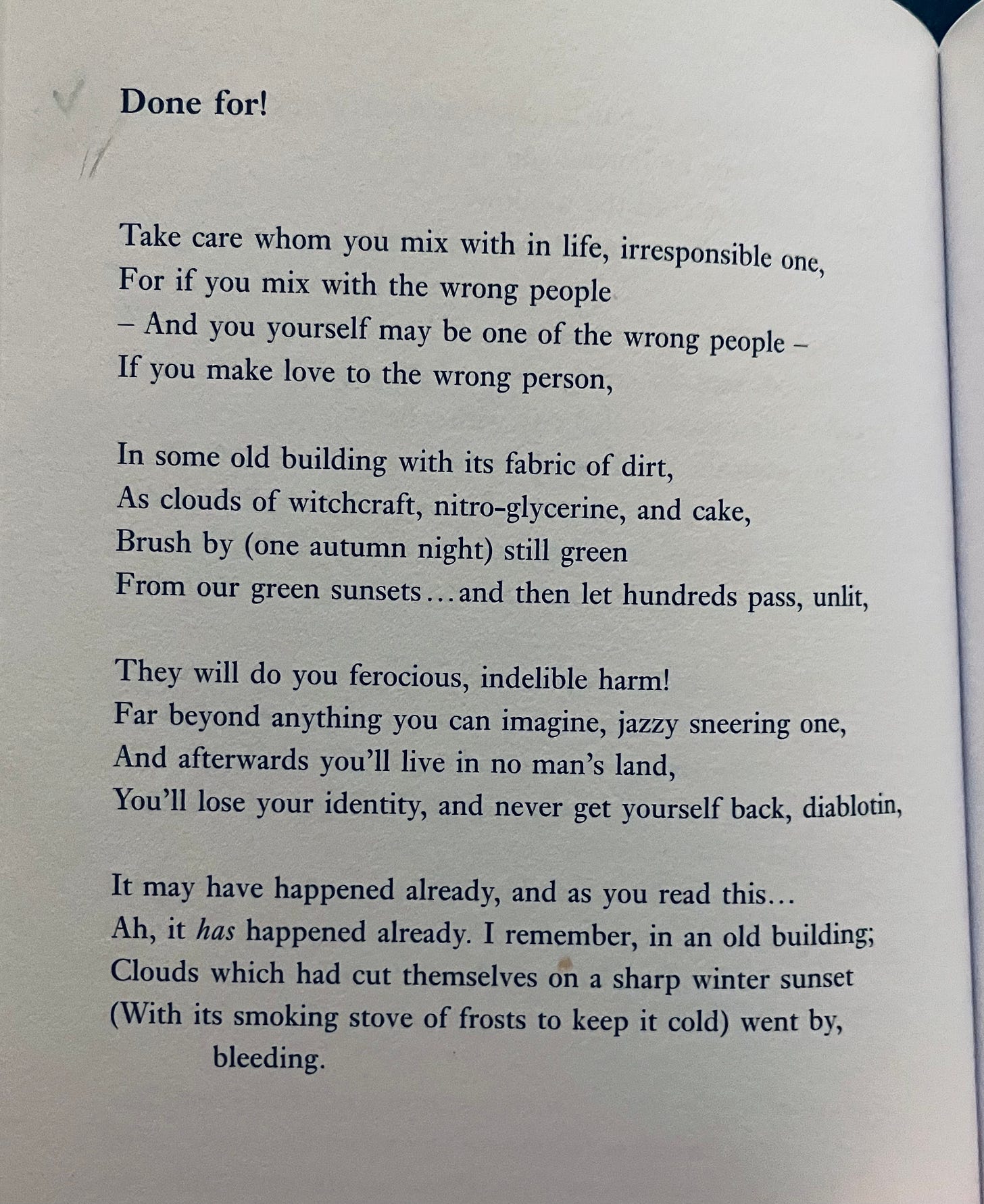

Take care whom you mix with in life

The surprise, intensity, and integrity of each of her lines (“And you yourself may be one of the wrong people,” “As clouds of witchcraft, nitro-glycerine, and cake,” “drablotin,” “Clouds which had cut themselves on a sharp winter sunset”) are enough to make the reading pleasurable; but it’s what she does with the poem’s psychological perspective that leaves you unsettled and breathless.

The poem refuses to pass responsibility onto others, the others who wish the speaker “ferocious, indelible harm;” instead, it reads like Cassandra—a warning to the reader that it also self-portraiture.

Criminal, you took a great piece of my life

Muscular and vicious, her attention to slights, betrayals, resentments, and frustrations. Tonks’s poems make their points and get their power from her razor-like diction and from syntax. Notice, for example, the change in syntactical register in lines that begin and end the second stanza in “Badly-chosen Lover:”

A poet’s main responsibility is to stay healthy. Yes, the world is sick. Yes, the world is dying. But the poet has to remain healthy enough to write the poems. For Tonks, this became increasingly dire.

When Tonks was 20, in 1949, she married Michael Lightband (they divorced after 20 years) and they lived in India and Pakistan, where she contracted both paratyphoid fever and polio, which atrophied her right hand. In response, she learned how to write with her left hand.

More health problems became devastating for Tonks the rest of her life: neuritis, two detached retinas, near-blindness, depression, borderline personality disorder, and finally ovarian cancer which killed her on April 15, 2014.

Initially drawn to Taoist healers and Eastern religions, she eventually rejected all spiritualism and converted to Christianity. She became devout and destroyed her collection of priceless Eastern art: she got a hammer and smashed her three Tang horses with riders, four Sung priests, Japanese warrior, Korean dancers, Chinese jade and bronzes, Chinese silks, Chinese rose apricot stone seals, marble terracotta, porcelain, plaster, mother-of-pearl, ivory, wood, and stone artifacts from around the world. She also took a novel manuscript (“the best thing I have ever written”) and burned it in an incinerator.

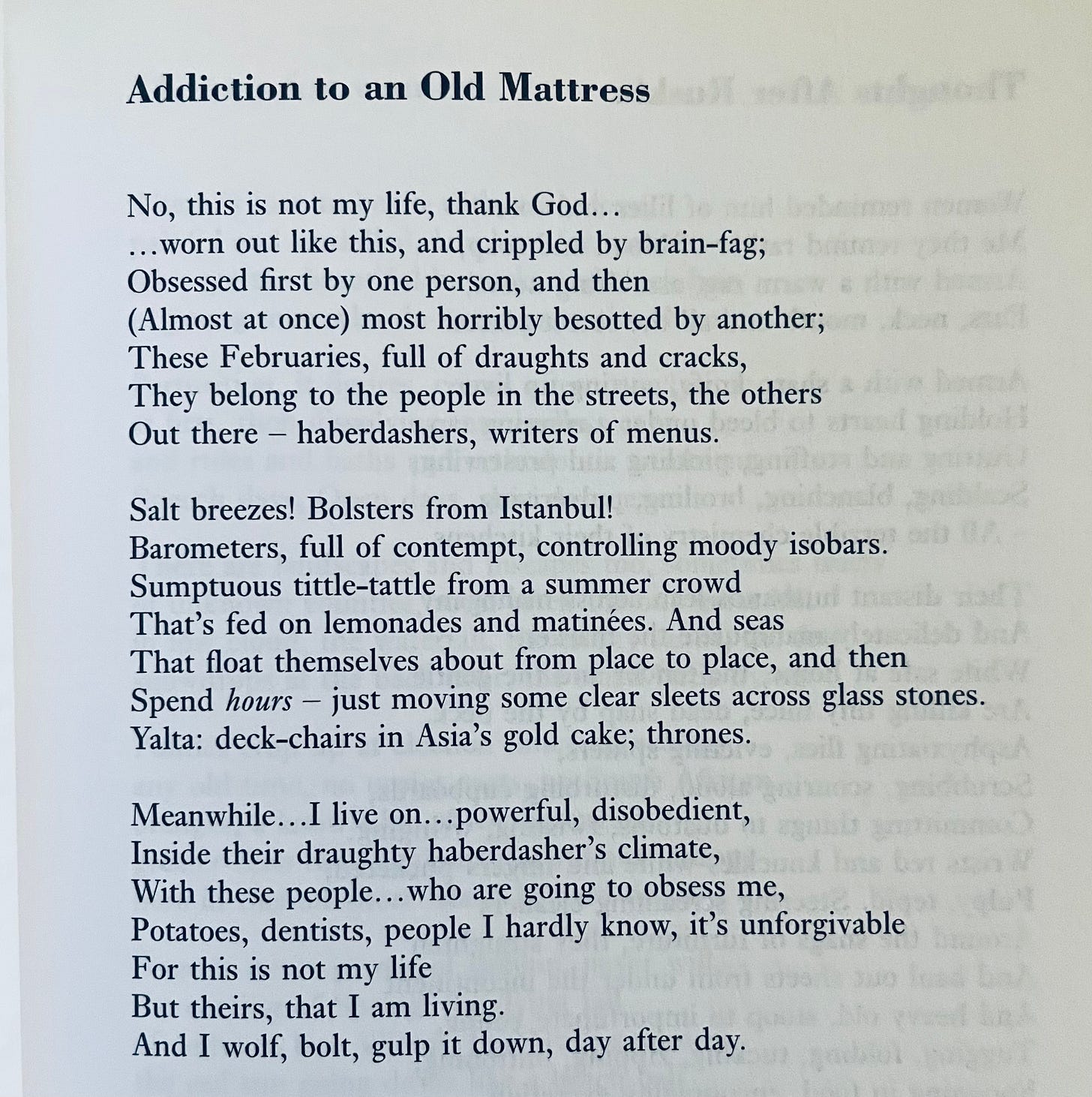

No, this is not my life, thank God…

Tonks makes un-understandable feelings like lust, regret, and animal drives into psychological thrillers. It is a quarrel with herself in the world, the willingness people have to drive into catastrophe, unstoppable urges that seem to swell up out of nowhere and cloud peoples’ decisions.

Her attention to nouns and verbs especially make the poems crackle with reading interest: “besotted,” “isobars,” “clear sleets,” “lemonades,” “gold cake,” “obsess,” “wolf,” “bolt.” This is very specific artistic choice-making.

Though “Addiction to an Old Mattress” begins with negation, or a reversal, it builds its case rhetorically. The poem’s subject, obsession, begins in confusion. The middle stanza is a list, then the hinge in the third stanza with “Meanwhile.” “Meanwhile” implies concurrence, overlapping, and contributory. For the speaker, obsession is “unforgivable.” Her mass of desires and penitence is made muscular, visceral; the feeling has blood in its veins.

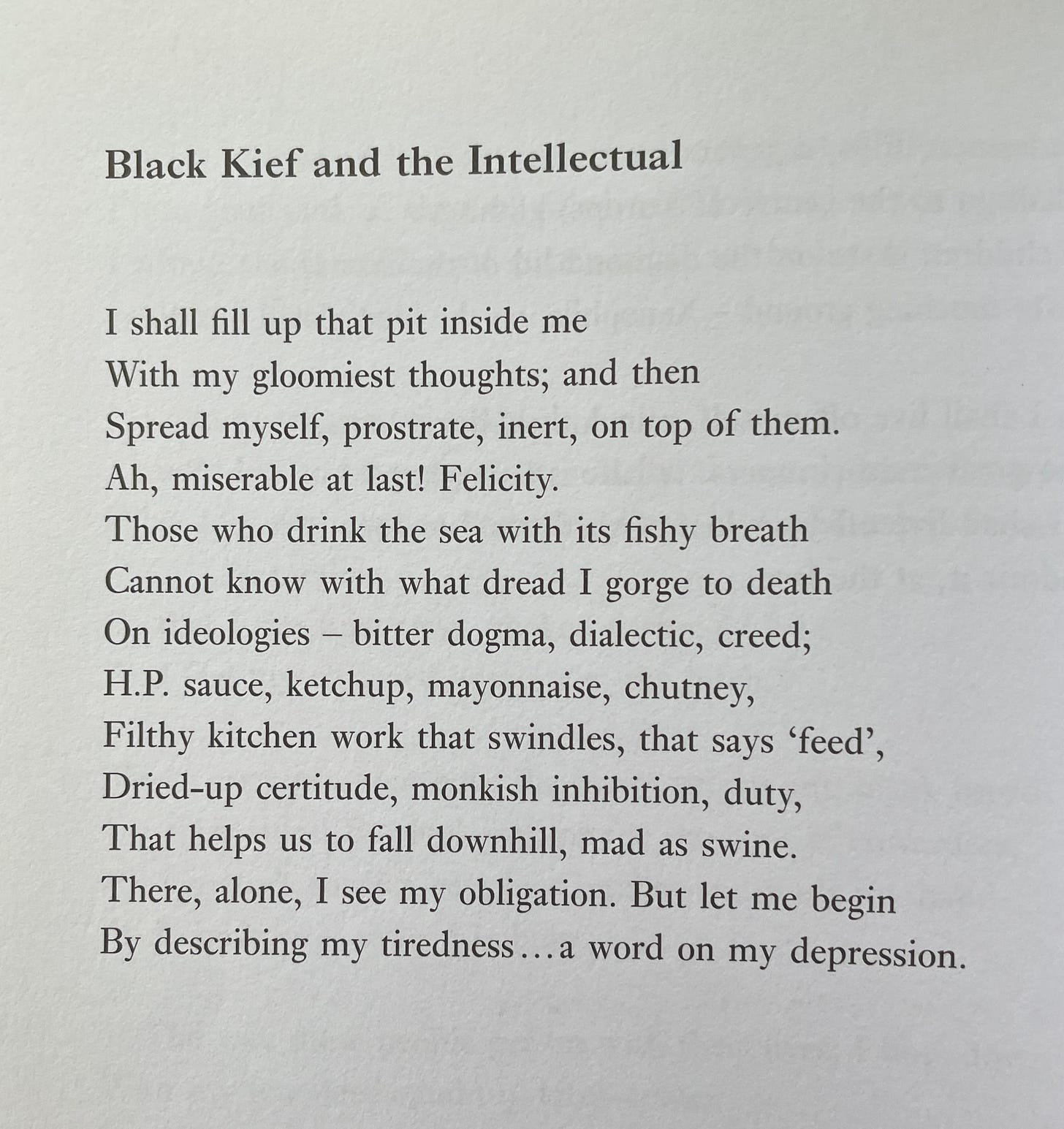

I shall fill up that pit inside me

“Black Kief and the Intellectual” is like a 13-line sonnet with a slant rhyme. It is a kind of gloss on depression. “Kief” refers to cannabis crystals, the pure collection of loose trichomes by sifting the cannabis flowers through a sieve.

The speaker, self-medicating, seeks to “fill up that pit inside” her, to “feed” her hungers, or to fill a pit that cannot be filled. Her diction contrasts clinical language (felicity, certitude, inhibition, obligation, dogma) with condiments and animal feeding (fishy breath, H.P. sauce, ketchup, mayonnaise, chutney, swine).

To imagine depression as an obligation is in a way to push everything into language—to use her experience, which is partly chemical and partly environmental, as raw material for poetry.

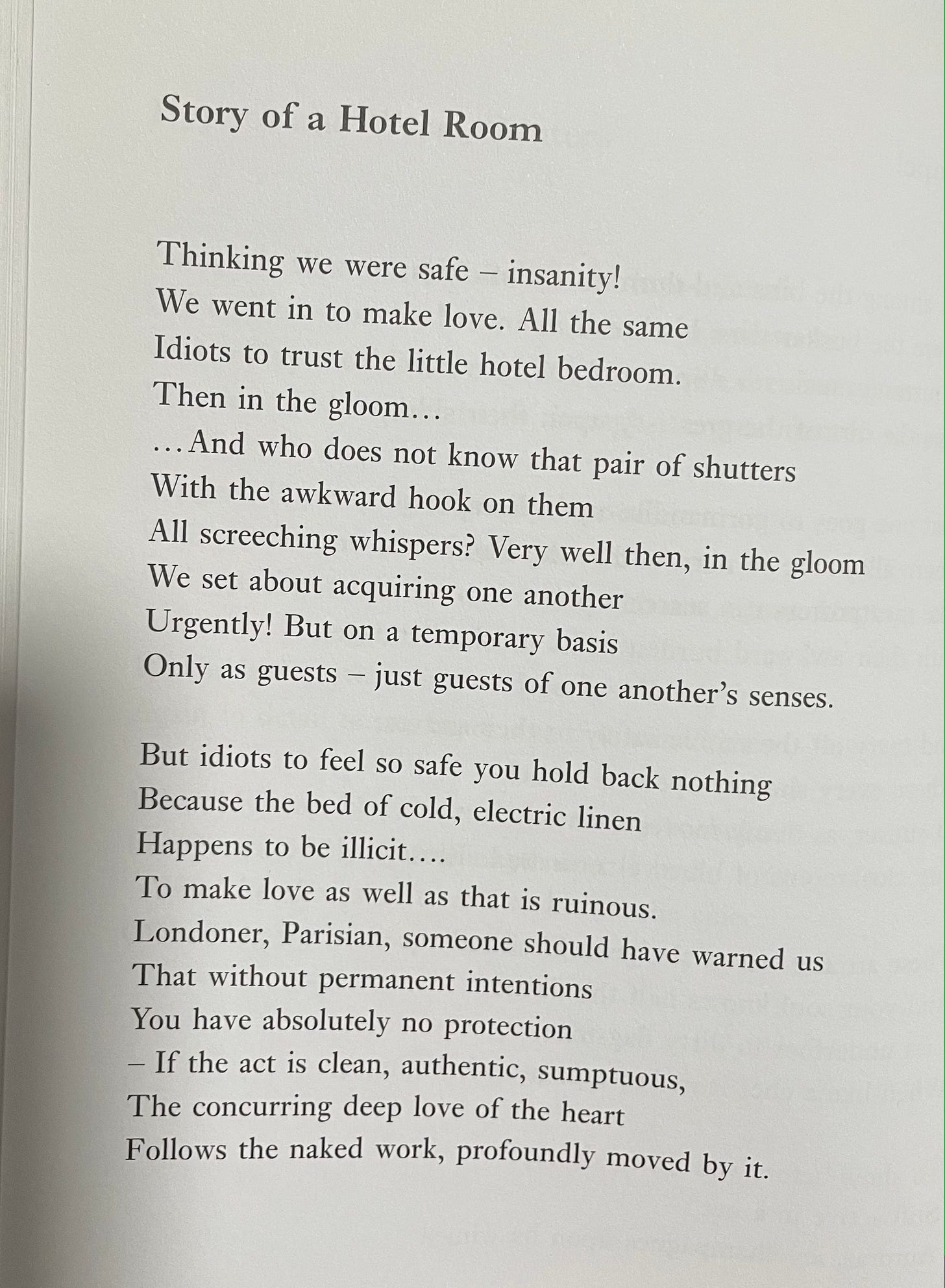

Thinking we were safe—insanity!

“Story of a Hotel Room” contains many of the threads and themes that bind her poems. It painfully brings clarity to self-delusion. People don’t do things for no reason, and part of being free means holding the capacity to make choices, even if they’re bad choices.

“In the gloom” the doomed couple “set about acquiring one another urgently.” They know they are insane and temporary: “guest of one another’s senses.” The poems shines a black light on the deception that some people twist themselves into to try to sever emotions from sex.

Tonks’s poetry is a supreme statement of moral taste. Her poems show a moral mind concerned with the ethics beyond harm and fairness. In poem after poem, she takes responsibility for all kinds of struggles with the self: loyalty and betrayal, authority and subversion, sanctity and degradation.

She rejects preciousness, art for art’s sake, or self-aggrandizement to the point of cruelty. Her aesthetics exist to give clarity and quality to suffering. Suffering—others’ and her own—was her true subject. She was not oppressed by failure, nor resigned to it. She made her poems from intimately moving into her responses to it, as deep as possible.

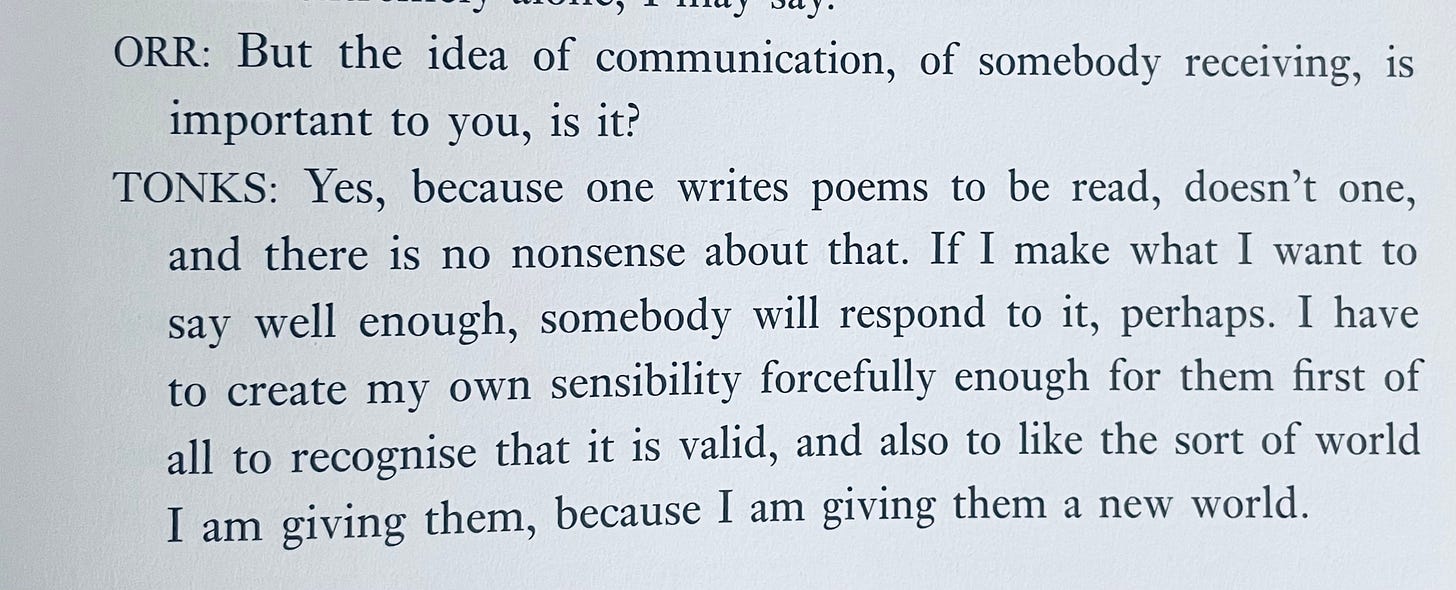

I have to create my own sensibility forcefully enough

On July 22, 1963, she made clear that her poetry fought over and over to not be eliminated. She exorcised demons without hurting people. She saw her poems as gifts to the reader.

More than the poetry of being inhuman, making wrong decisions, and being depressed, her poetry is the fierce devotion to using everything for the poems. The new world we are given can’t be found anywhere but there.

For further reading:

Tonks, Rosemary. Bedouin of the London Evening: Collected Poems & Selected Prose. United Kingdom: Bloodaxe Books, 2016. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

Sean Singer Editorial Services

...damn. Gotta get back to keeping up with this Substack, Sean. Thanks for the Tonks...

I’d not known about Tonks’s life and work, so thank you for this profile, Sean. I feel much compassion for her, and think I can understand why she stopped writing poems (at least for public consumption).