Russell Atkins (b. February 25, 1926) is a major figure of experimental poetry, but outside of his hometown, Cleveland, he is little known and hardly read. Besides poetry, Atkins is also a composer and he has a completely idiosyncratic way of thinking about both poetry and music. Atkins insists that he makes poems like a composer and writes music like a painter.

Until 2019, when Michael Dumanis and Kevin Prufer released a book of Atkins’s selected poetry, there was only a single book, Here In The. It now exists only in archival copies. Atkins was always in the vanguard of what would happen in poetry. His devotion to language is an aesthetic experience; Atkins wants poetry to be a process of human thought, and as a method to break the barrier to access of other minds.

At the peak of his abilities, Atkins corresponded with Marianne Moore, Amiri Baraka, and Langston Hughes. Despite this, he’s been pretty much unknown to readers of poetry.

Urban life, and specifically Black urban life is important to his work. Cleveland, and the cultural imagination of Cleveland, are a “main character” in most of Atkins’s work, and his ties to Cleveland also tie him to two of his poetic fathers, Hart Crane and Langston Hughes.

Cleveland is a majority Black city, and Atkins uses his poetic style—a “beyond category” approach to language—to illuminate the tensions between the aspirations Cleveland’s Blacks had for the so-called “American dream” even as Jim Crow’s barriers to entry into that dream made obstacles to realizing them. Cleveland, with its frigid winds and low brick buildings, is divided into several neighborhood districts, and these are identified by whether they’re east or west of the Cuyahoga River.

One quirk of Atkins’s poetry is that there are often multiple versions of the same poem, not unlike the way there are multiple recordings of Charlie Parker doing “Star Eyes.” “Lakefront, Cleveland,” for example, a poem that expresses Lake Erie’s consciousness, exists in two versions.

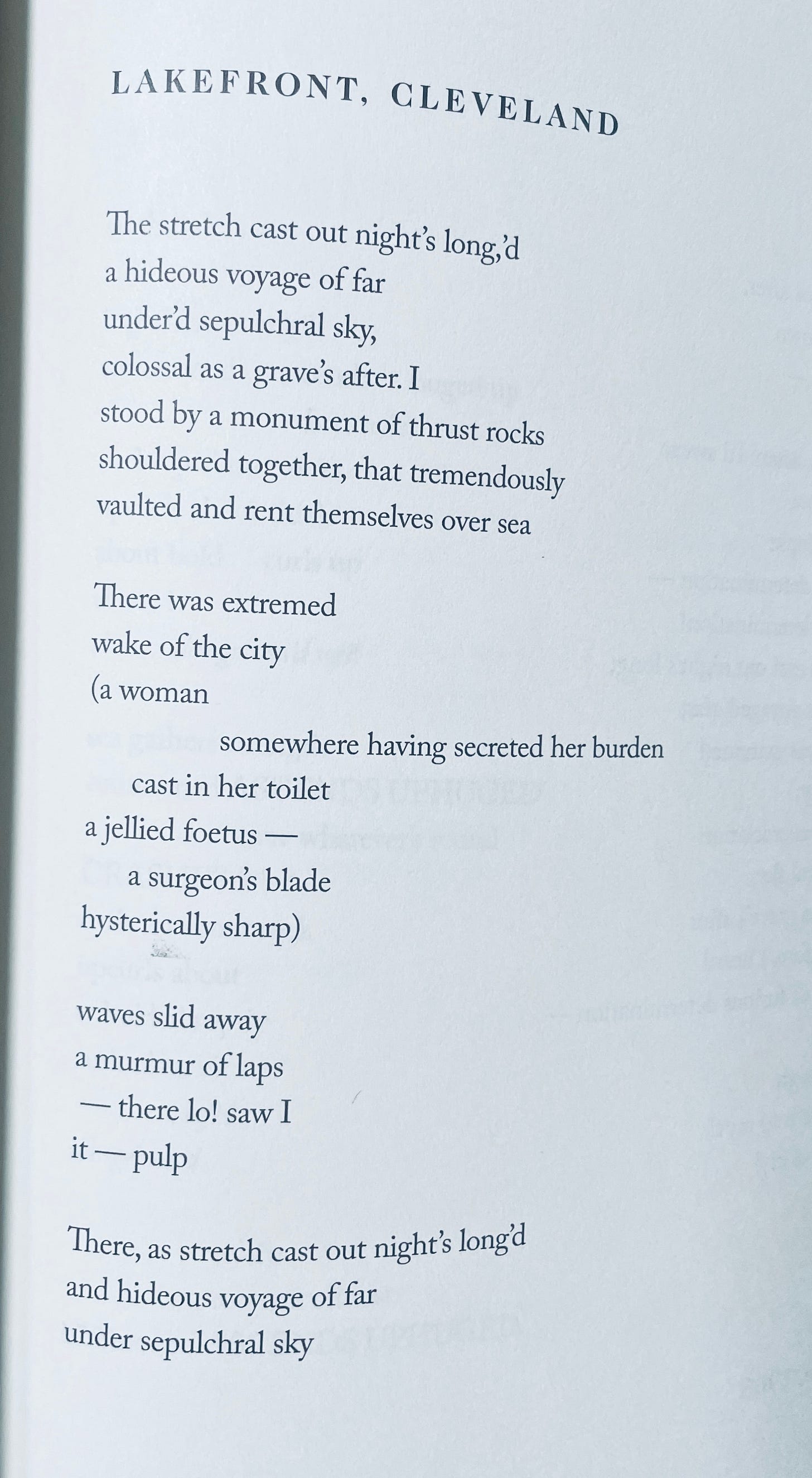

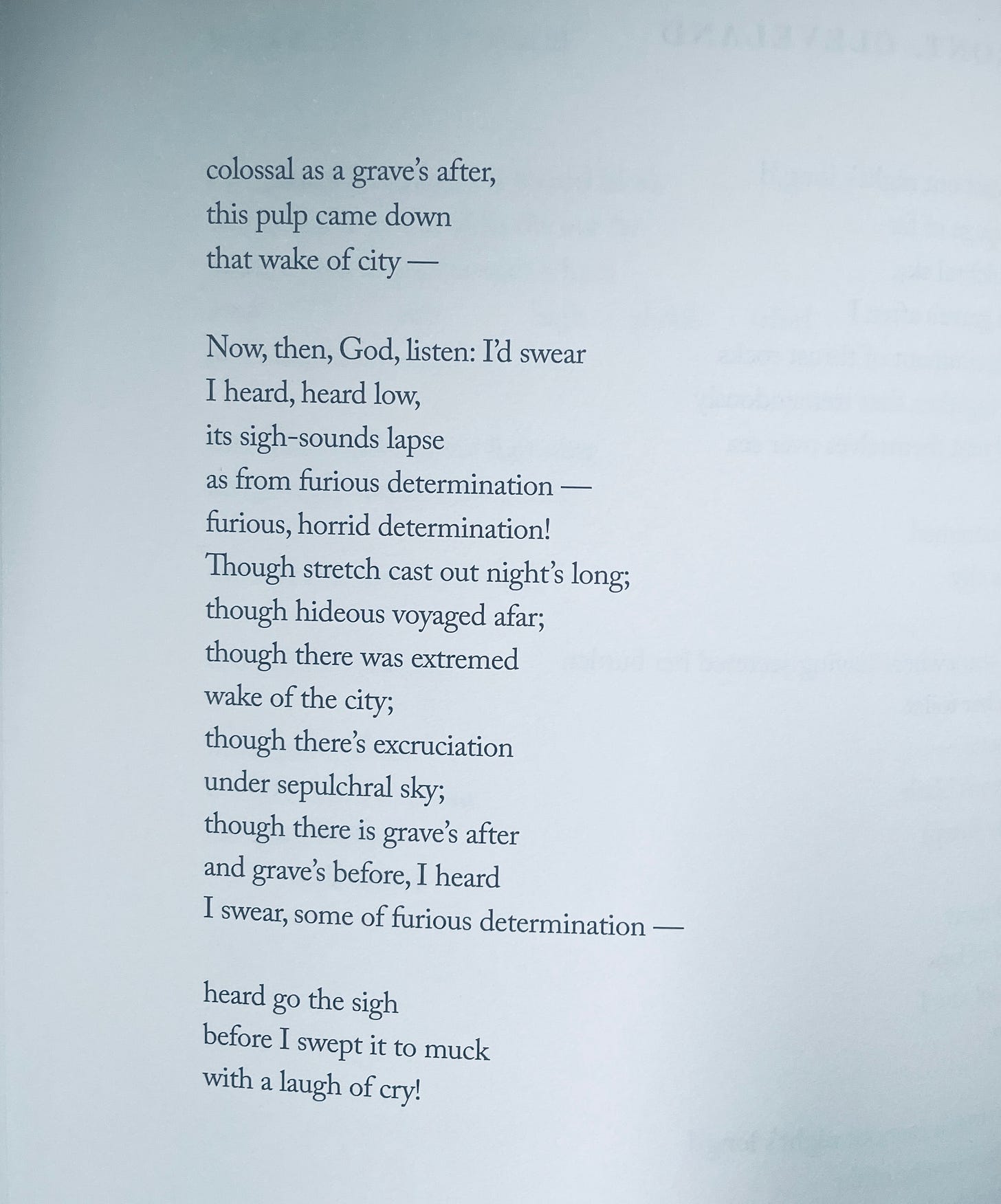

Version A, from 1968:

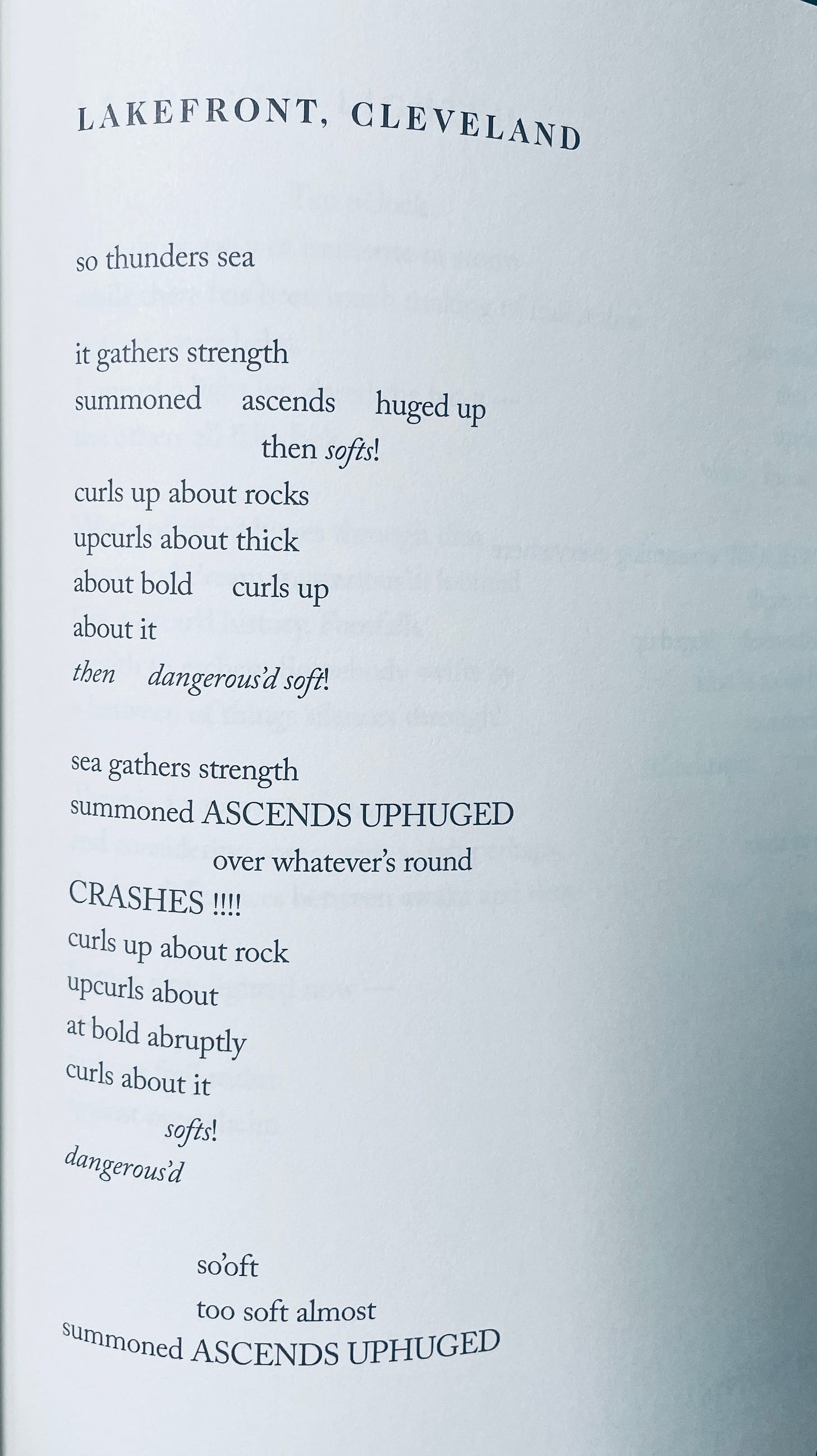

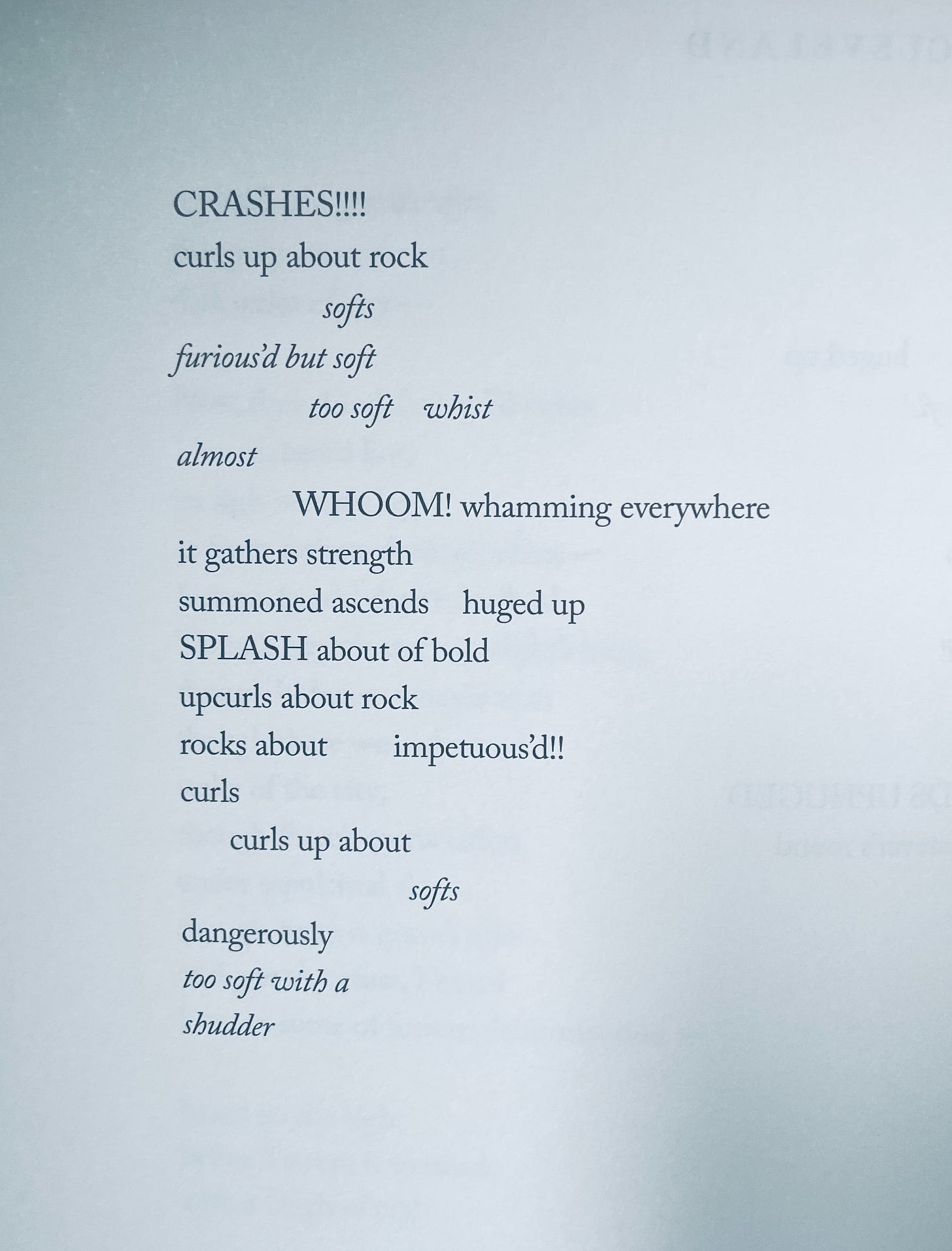

Version B, from 1976:

Some districts in Cleveland, like Shaker Heights, had racially mixed populations and were middle-class. A former industrial place, Cleveland also has many mixed-use areas that reveal its past in steel and manufacturing. Parts of Cleveland are violent, and this mayhem is bound with its Jim Crow past; for example, besides exclusion from hotels, businesses, and restaurants, Cleveland had no parks near its Black districts.

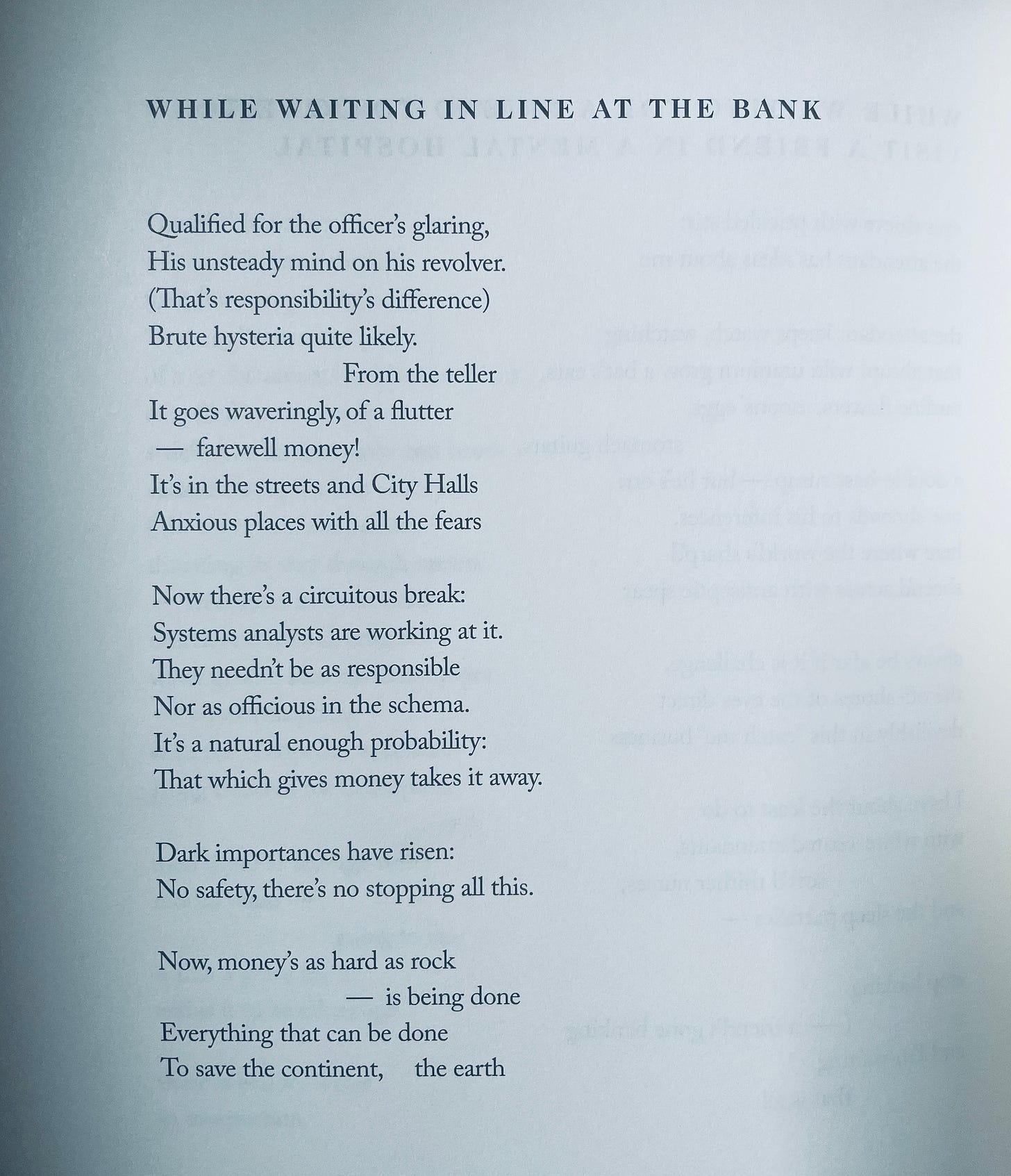

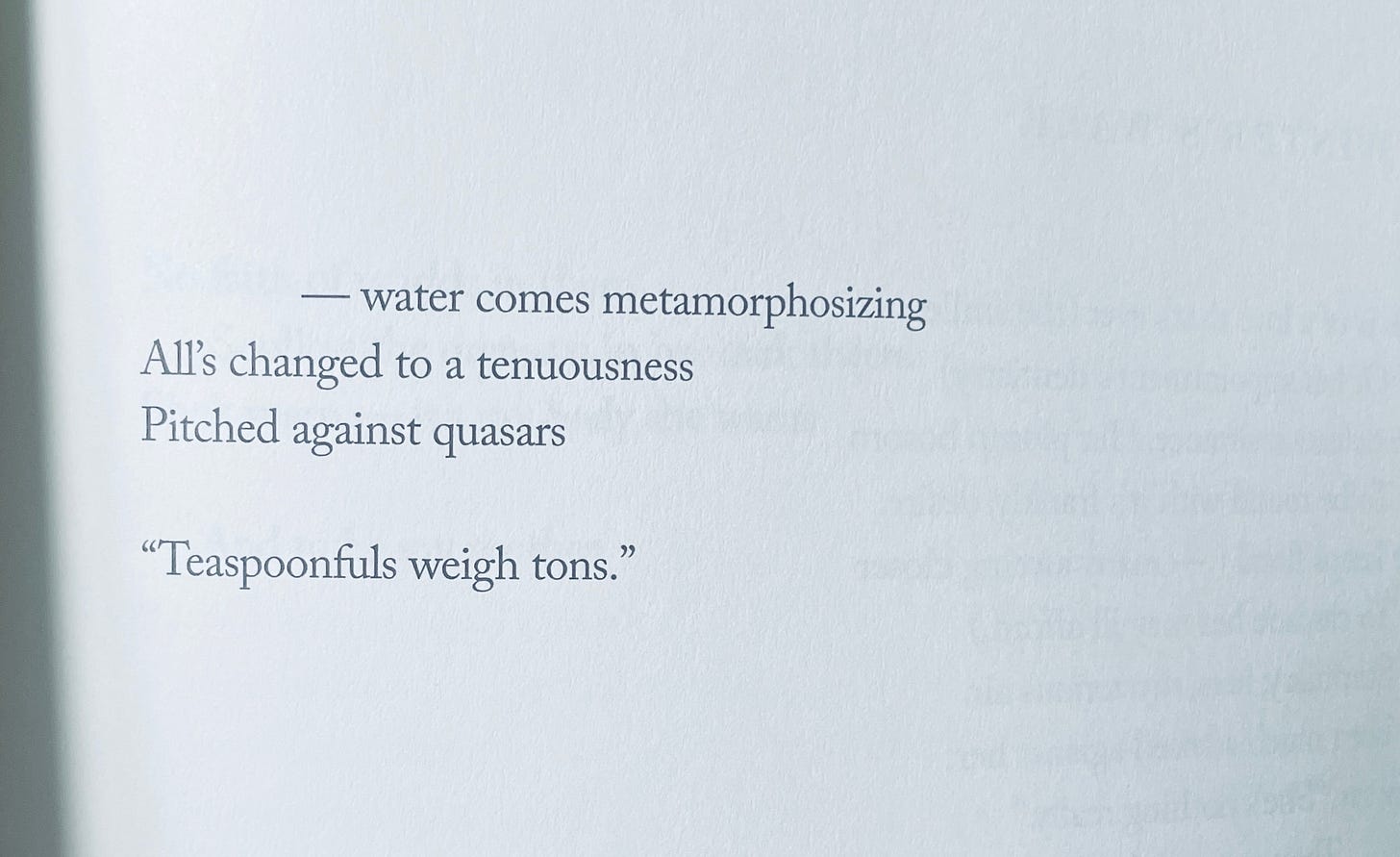

“While Waiting in Line at the Bank,” evokes the insidious practice known as “red-lining,” a process wherein Blacks were barred from getting loans to buy homes. The speaker becomes increasingly anonymous after a “circuitous break” and is no longer seen as an individual. Frequently there is an oblique tension in Atkins’s urban poems in which private memory and public space align in some surprising ways.

Atkins also shows how the city’s marginalized citizens, particularly the sick or elderly, deserve our particular attention. Atkins describes Cleveland as a landscape; he does not do portraiture, but often describes it via a removed speaker, who is embodied by the passionate syntax in the poem. Like Hart Crane, Atkins is interested in perceptions. His poems are expressionistic and impressionistic.

Both Atkins and Crane were raised in somewhat coddled circumstances, particularly by their mothers. Yet, where Crane was expected to join his father’s candy manufacturing business, Atkins was raised in an environment of artistic refinement (e.g. Enrico Caruso, piano lessons, Latin lessons, painting) and was expected to become an artist. His family, though, was anti-jazz (sometimes called “Black Classical Music”) and anti-blues, which was turned off because it was “bad, naughty.” This affectation was common among Black bourgeoisie in the 1920s.

Around 1928, when he was two, Atkins was hidden in a broken-down room by his Gramma who sought to protect him from a “hant,” or haunt, who darkened his complexion and wanted to make their lives miserable. These hants have a long history in Afro-American musical lore, particularly the blues, and are related to “goofer dust,” “hoodoo,” “jinxes,” “mojo,” “juju,” “gris-gris,” and “zuvembies.” Gramma Atkins would murmur to her hant all day, and believed Russell’s phenotype to be caused not by genetics, but by their devious machinations. Atkins’s early recollections of this hant is related to his uniqueness, his “beyond category” status as a writer insofar as it allows him to write without fear of ghosts, the memories of parents and authority figures. Hant is also a habit, wont, custom, or usage; all of which Atkins’s work shows fleeing from, liberating from, and vying against.

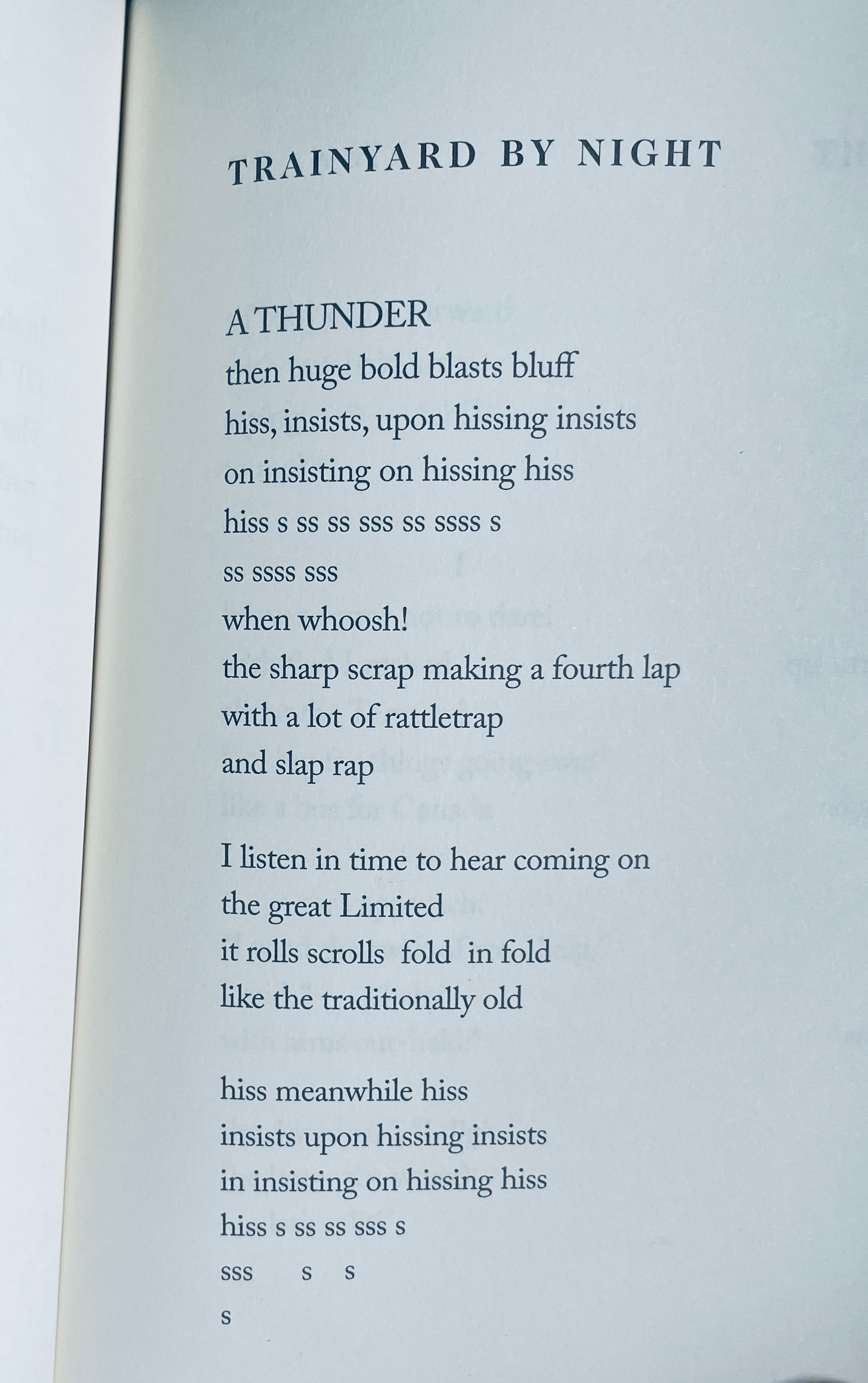

Atkins was dedicated to all things avant-garde, and his magazine, Free Lance, launched in 1950, reflects that. He has consistently written deliberately outside poems, echt-left-of-center stuff. The poems are not meant to communicate so much as they are objects built from language. He is interested primarily in aesthetics: highly figurative language, the use of the apostrophe –d to exaggerate and disarrange grammar, and intervallic leaps.

His figurative language is often as fresh now as it was when it was written; it pushes against the pressure of the line and shows moments of ecstatic beauty:

Measure his blood pressure then by / the wildest tendrils / both overgrown / both by the cruel’d edges (“For a Neighbor Stricken Suddenly”)

the heap up twists / such / as to harden the unhard and unhard the hardened. (“It’s Here In The”)

Thunder crammed in a moan. // Craze of the seascape! (“Lake in a Storm”)

Oh didn’t it “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ // rain / “ “ / “ “ (“Spyrytual”)

Old friend, listen: don’t wait / —when they come at you, / throw it at them! (“Old Man Carrying a Bible in a High Crime Area”)

stir of a wish? // a wraith waving a grey scarf (“Irritable Songs”)

snow hates the body // and fashion (“Idyll”)

I drew to her while she / into the air / smiled x / THUNDER (“A fantaisie”)

As these few examples illustrate, many of the tropes common to his work—repetition, rhetorical transversal, a comic voice amid the gloom, and the use of white space as a mode of interrogation—show themselves frequently in his work.

Atkins’s most inimitable sonic characteristic, though it has a long history of precedents in English poetry, the apostrophe –d, appears all the time: weary’d, skull’d, antenn’d, up’d, thrall’d, quick’d, stark’d, vicious’d, torso’d, slab’d, etc. He appends the apostrophe –d to both verbs and nouns, and it seems to instantly freshen or sharpen the syntax. Atkins says he “resuscitated it, so to speak, to specify a bold distortion of the weak verb which I use to exaggerate and disarrange the grammar.” Oddly, its effect is both formal, because of its link to Chaucer, Whitman, and others, and also informal, because of its relationship to spoken language on the street; the clipped ends of words, quickly said.

Another interesting quality of Atkins’s work is related to the apostrophe –d, what he calls “intervallic substitutions…the avoidance of the strictly diatonic in harmonic modulation in avant-garde (or contemporary) ‘musical’ composition.” In terms of jazz, Atkins’s contemporary, Eric Dolphy is known to have used intervallic substitutions as a defining characteristic of his work. It is interesting to note that “interval” literally means “the space between ramparts,” and its common abstract meaning, “interval of space or time,” is derived from its concrete meaning. These intervals in Atkins’s poems reduce their function in terms of sense, but often heighten their imaginative leaps, metaphoric capability, and move their speakers’ psychic distance from wide to close-up.

Atkins’s aesthetic is an embrace of the African-American human being and a rejection of both cultural nationalism and cultural antebellumism, a psychology that expects people to stay in their place. In terms of poetry, Atkins is all about adding possibilities instead of cutting off possibilities.

Poetry is a solitary activity, albeit a functional and communal art with a strong oral artist in the middle of the circle. Atkins, like Hughes, was in and of the community.

Atkins is a completely unique voice in American poetry; though he is challenging for most readers—to paraphrase Atkins, much music pours a supra light, as if it were preternatural grief. There is a pathos in his poems, related to his urbanism, that connects private and public memory in a fresh, fantastic way.

For further reading:

Atkins, Russell. World'd Too Much: The Selected Poetry of Russell Atkins. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2019. [Buy at Bookshop]

Dumanis, Michael and Kevin Prufer, eds. Russell Atkins: On the Life and Work of an American Master. Warrensburg, MO: Pleiades Press, 2013. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

Thanks for introducing me to Atkins's work and life, Sean. This stood out to me: "Atkins’s aesthetic is an embrace of the African-American human being and a rejection of both cultural nationalism and cultural antebellumism, a psychology that expects people to stay in their place. In terms of poetry, Atkins is all about adding possibilities instead of cutting off possibilities."

As a wild coincidence, I typed up the manuscript for Atkins’s book in connection with some work done years ago for the CSU Poetry Center. So great to see him recognized here!