Craft: Short Poems

Pascal, Kumin, Justice, Creeley, Clifton, Bashō, Valentine, Hughes, Merwin, Celan

Blaise Pascal, letter 16, Les Provinciales, 1657:

Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.

[I have only made this [letter] longer, because I have not had the opportunity to make it shorter.]

Recently on Twitter someone was complaining about short poems, that they more resemble the beginning of poems rather than complete poems. Where do these notions come from, and at what point are they sent to the pasture? If poetry is about compression, then it would follow that short poems are more ideal than longer ones, and silence or blank space is closer to the perfect poem in the mind’s eye.

How do short poems function? Can they do things longer poems can’t? A poem has to do so many things in a short space. Some poems are like little jewels, or a portrait in a frame. They don’t have a lot of vertical movement (e.g. Emily Dickinson, Lorine Niedecker, Robert Creeley, Jean Valentine, Robert Lax). Other poems are like a horse running through a river and have longer lines, and much more horizontal and vertical energy (e.g. Walt Whitman, C.K. Williams, James Schuyler, Ai, Lynda Hull).

The long poem is often more like a telescope—the expanding tube gets longer and longer until it has to be propped-up with an arm. The short poem is a frame within which what’s unsaid becomes as important as what’s said.

Short poems contain more withholding, more implication, and more interpolation. Because of their immediacy, short poems can often penetrate what T.E. Hulme called reality’s “intensive manifold.” They can reveal and conceal, deny or confirm the elements that seize up in a reader and push into a swirl of new meanings and vistas.

Short poems are an utterance, with force. There is also historical precedent for them in the form of hymnals and of ballad meter, or common meter, which is unforgettable. Its stresses per line are 4-3-4-3. Such poems are also easier to memorize, which is a value in and of itself.

Maxine Kumin insisted her students memorize 30-40 lines of poetry a week. “The other reason, as I tell their often stunned faces, is to give them an internal library to draw on when they are taken political prisoner,” she told The Times-Picayune of New Orleans in 2000. “For man, this is an unthinkable concept; they simply do not believe in anything fervently enough to go to jail for it.”

30 lines a week is 1,560 lines a year. 40 is 2,080 lines a year. If only we all could have that many lines of poetry ready in our mind at all times—imagine the poems we could write.

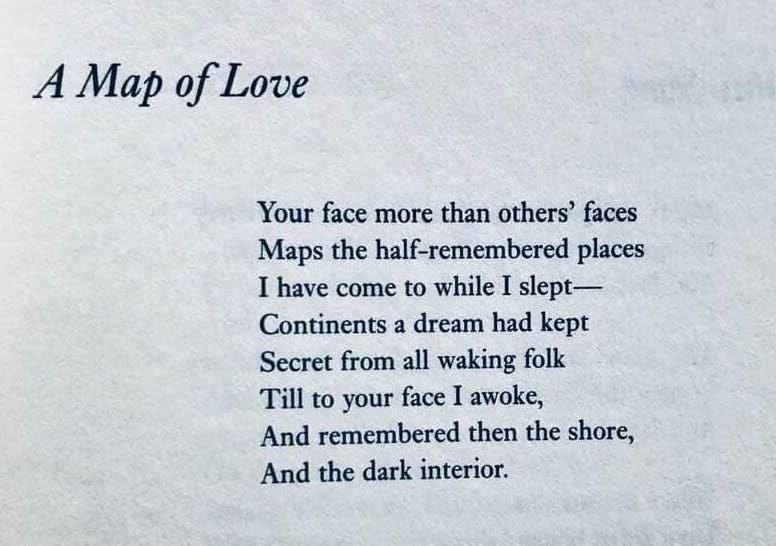

A Map of Love

Donald Justice’s “A Map of Love” shows the potential of form in a short poem. Justice was a master of formal constraints, subtlety, and sound.

The volta in line 6, “Till” implies an ongoing dream that is interrupted by memory (previously half-remembered). The minor key slant rhyme “shore” and “interior” mirrors in form what the poem is saying.

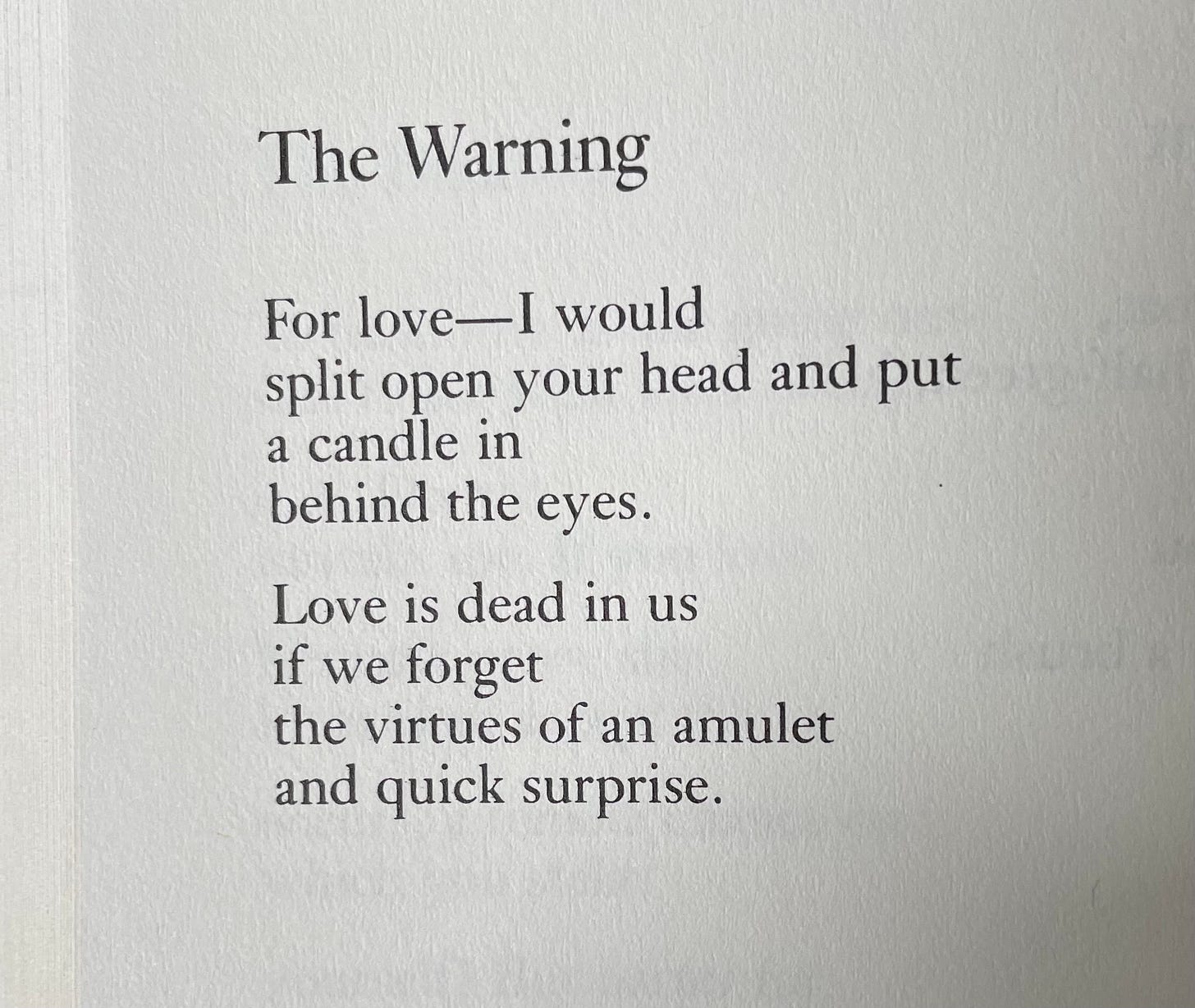

The Warning

Robert Creeley’s minimalist sensibility is apparent in many of his poems. “The Warning” does a lot in two brief quatrains.

This poem also uses rhyme in a clever way: “eyes/surprise” emphasizes the light the speaker has put into his beloved’s head; similarly, “forget/amulet” suggests the thing put there—candlelight—gives her protection against evil, danger, or disease, and that this action should be remembered.

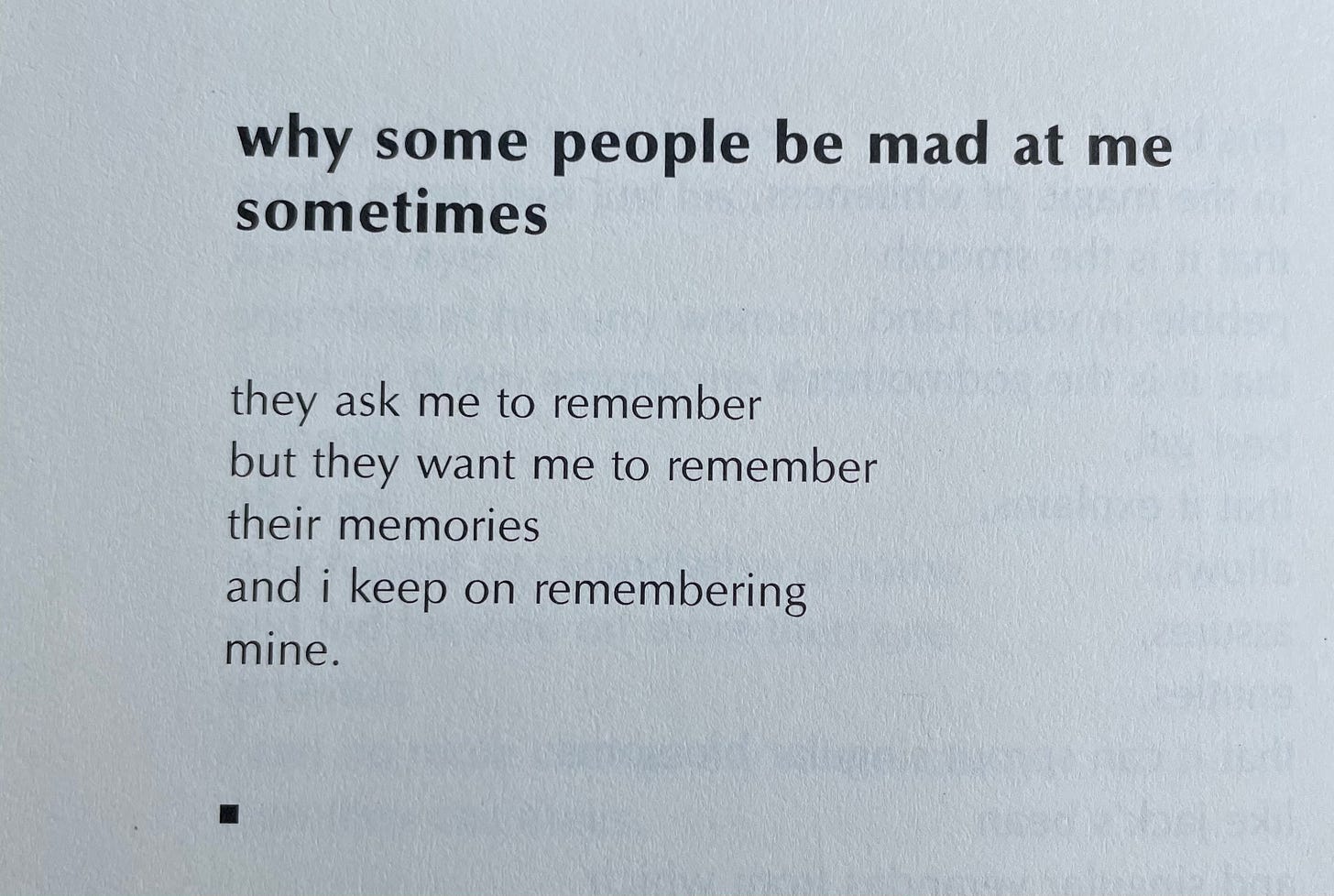

why some people be mad at me sometimes

Lucille Clifton had an ability to convey a deep moral sensitive and power in her poems. Her poem “why some people be mad at me sometimes” is very short, but shows a complexity of thought and feeling that is hard to replicate.

The poem expresses the superficial concern others have, especially for writers who are given the responsibility to record and bear witness. But the poet cannot remember their memories; her obligation is to be truthful about her own.

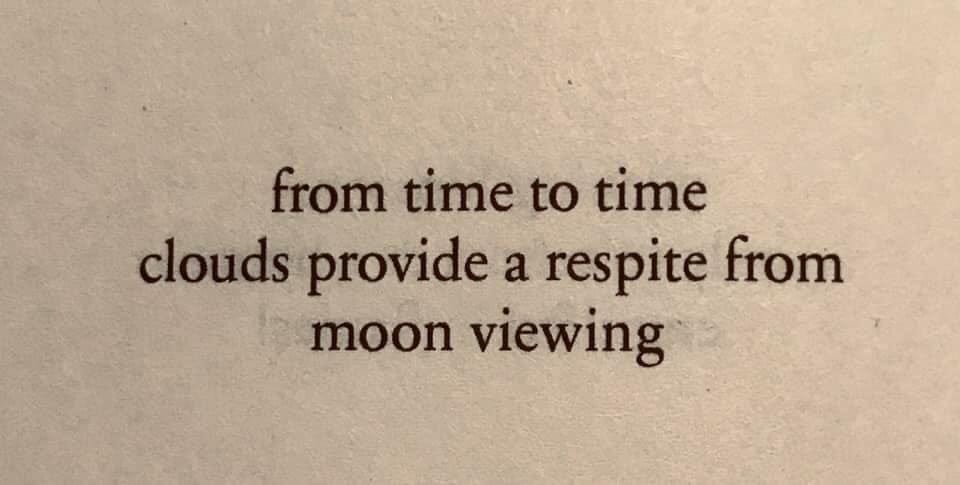

from time to time

Matsuo Bashō, of all the Japanese poets, had a capacity for conveying this moral taste. His poems often show the mixed feelings people have for simple experiences.

The clouds provide something; they give us a break from moon viewing. Of all its mentions in poetry (the moon is now thought of as a cliché), it rarely is depicted as something to get respite from.

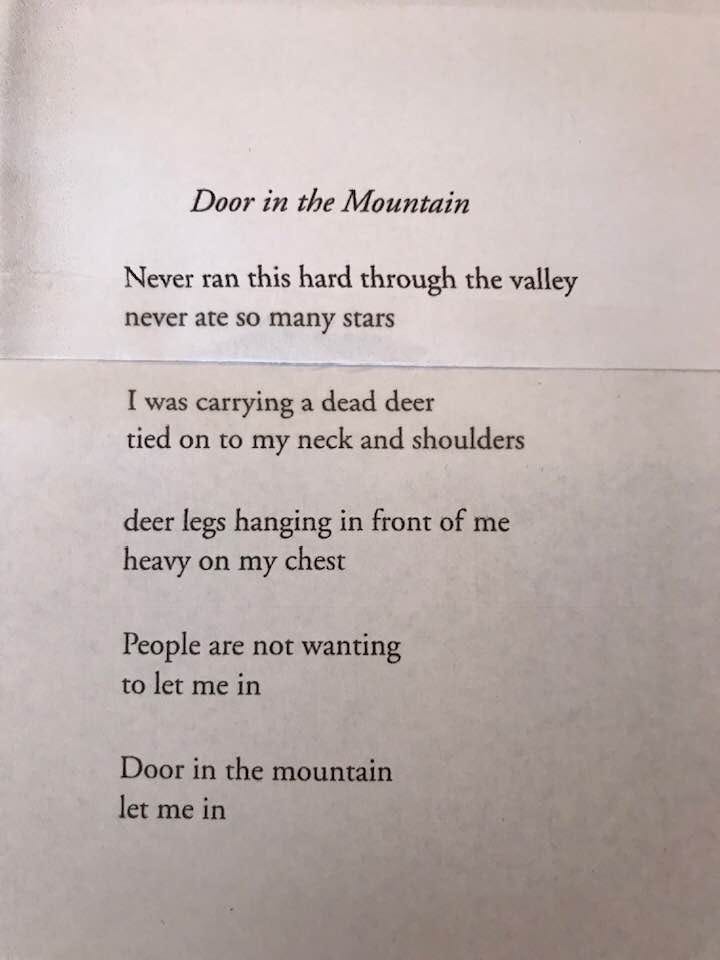

Door in the Mountain

Jean Valentine did not write in a straight ahead way; her poems are oblique and tend to deflect, holding space for the reader to find their own ways into the poems. “Door in the Mountain” is five short couplets.

The couplet is the most vulnerable of all the forms because of they are so exposed. Couplets are really about intimacy and relationality. Their spareness gives the false impression that they're easier, but they're more difficult to pull off than stanzas in quatrains, or other forms. Perhaps the deer is the speaker’s difficulties, traumas, baggage, or fears. The door in the mountain is perhaps a place of solace, or just a terminal on the way to somewhere, but people are not wanting to let her in. The core of the poem is about people even though the poem does so in an elliptical way.

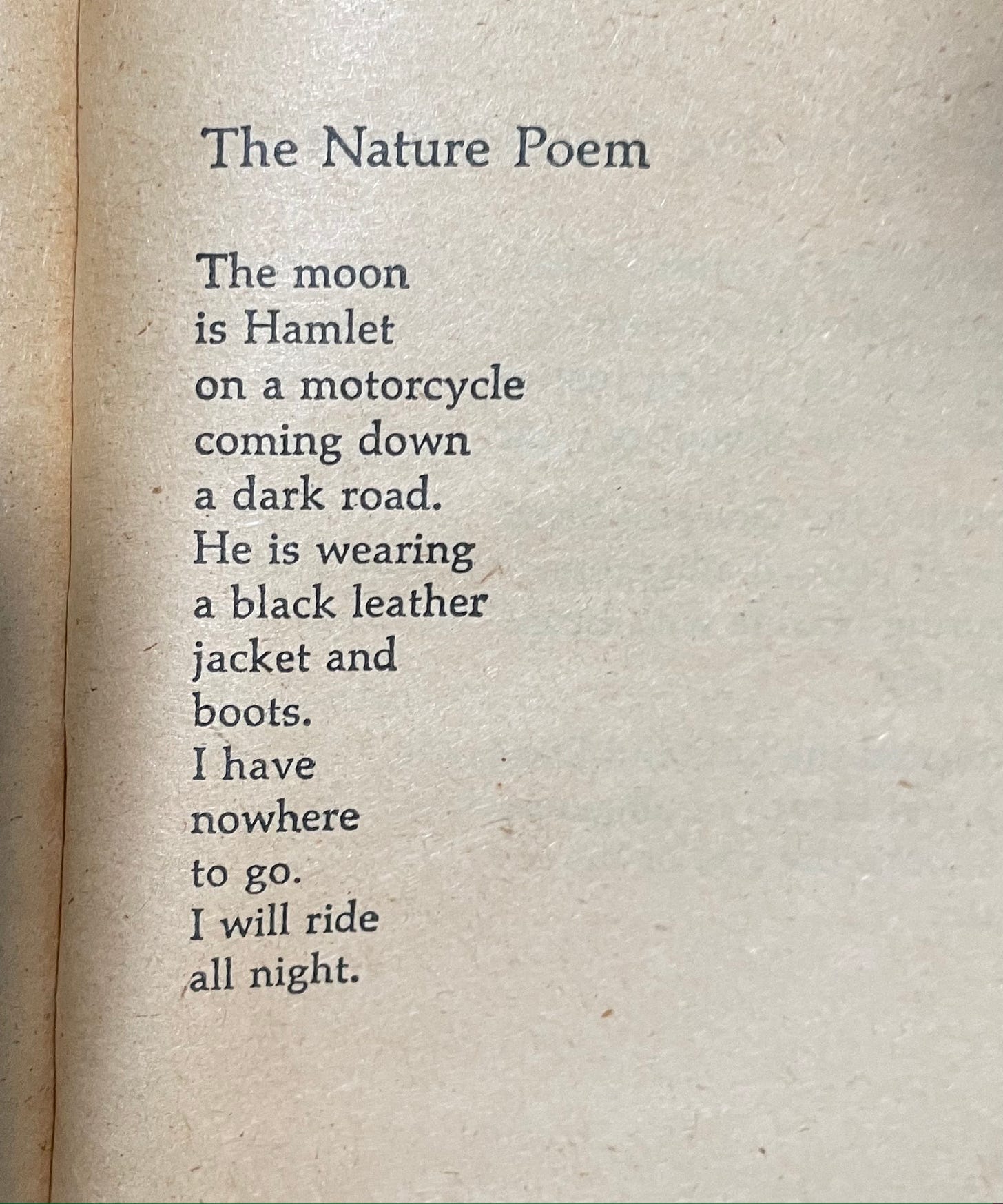

The Nature Poem

Richard Brautigan is a poet I admire because of his ability to retain a childlike approach to metaphors. Brautigan’s ideas and presentation of his poems prefigured the social and sexual changes of the 1960s even though he was much older than the counterculture he inspired (he was born in 1935).

Here, the moon shows up again, again in a surprising way. Using a simple simile, the moon “is Hamlet on a motorcycle coming down a dark road.” The turn in line 10, where the poem becomes first-person is in the voice of that moon. Brautigan was able to turn whimsy and mystery into poem that are often poignant and have more gravity than they appear.

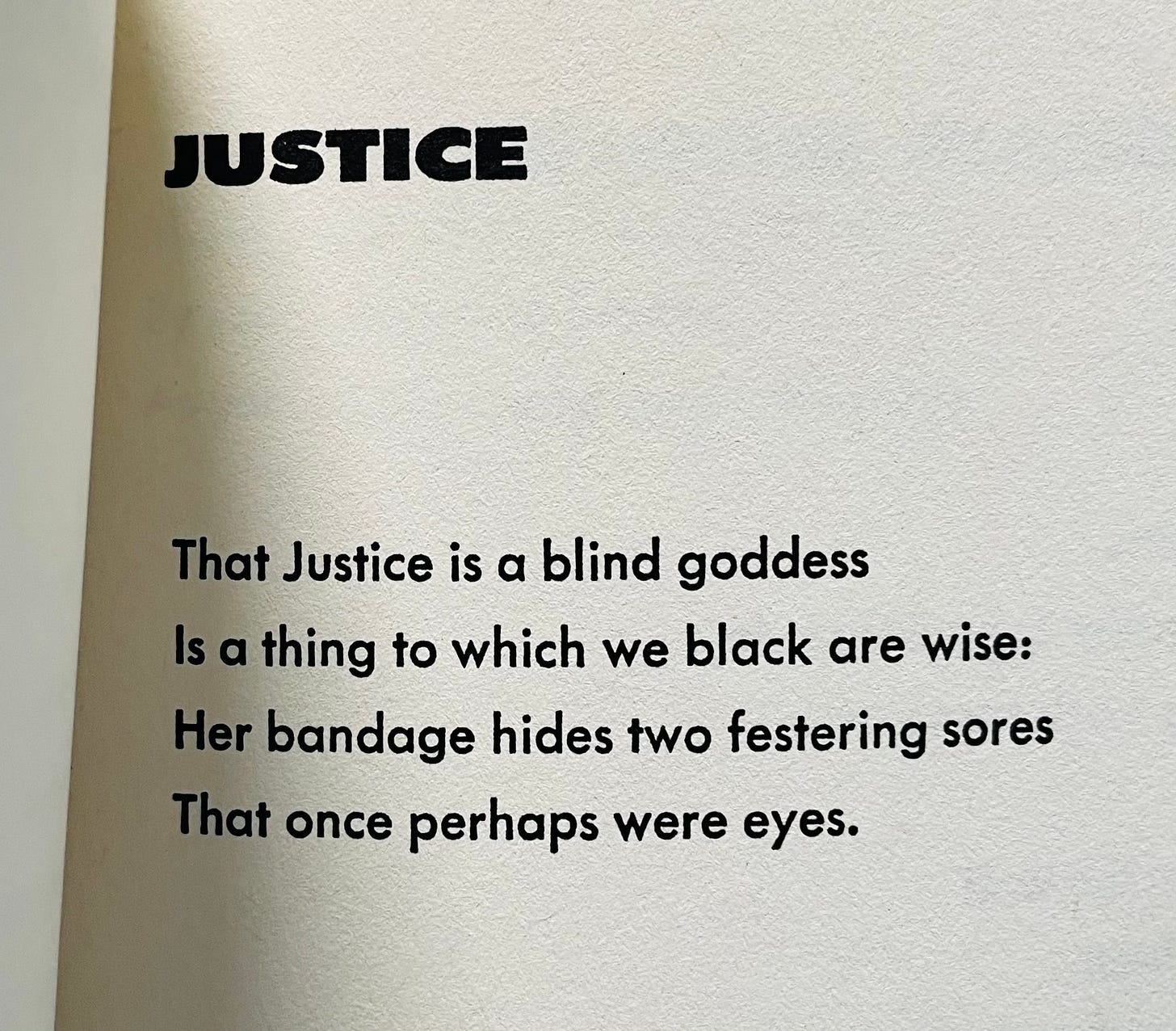

Justice

Langston Hughes used both blues as a form and as a sensibility. He was always a passionate Leftist and was put on trial by the House Un-American Activities Committee. “Justice” shows his attention to racial equality and American culture that keep his poems nervy and relevant; this could have been written this morning.

Taking the figure of Justice literally, Hughes imagines that her bandage, rather than assuring equality under the law, is actually a monster with “festering sores.” The ABAB rhyme reinforces the way this deformed concept of justice is formalized in all of American systems. Finally, the poem is in the first-person plural, so his poem has a populist edge without being didactic.

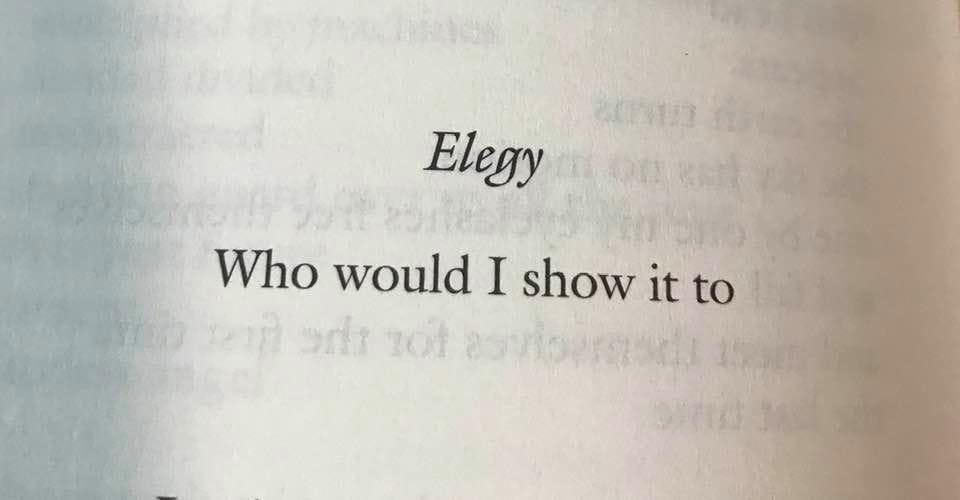

Elegy

W.S. Merwin’s “Elegy” is perhaps the shortest poem I know.

Elegies in the sense that Catullus knew them were written in heroic couplets. In Merwin’s iteration, the other half of the couplet is missing. It’s both a rhetorical question and a statement that has no final punctuation mark. This suggests that the elegiac feeling is continuous. The poem implies that the elegy is unwritten, except for the poem itself. The person the elegy is for is no longer there to receive it.

Short poems are not the openings to longer poems. They are their own species: fierce, direct, aggressive, open, and final. They are wolves, not dogs. If ever there was a master at the reduction and invention of language to express what is unknown in a concise way, it was Paul Celan.

The “missing out” is that short poems are not intended for a reader to catch their breath. “Breathlessness” is partly the entire point. Poems can omit commas or conjunctions, the connective material between ideas. The imaginative leaps do not require this material.

Poems come from what Dickinson called the “tumblers of clover.” The poem is enjoined to the flesh and the brain, the catacombs of memory, and the pure place that remains undefiled from all abominations. Eternity is coming in the form of rising seas and sucking air, obliterating the birds. Poems can help us uncoil from this inevitability. Thoreau observed that Imagination is wounded before the heart, and it is in those veins that we can say what we are (and were) among the charred outlines of trees.

For further reading

Brautigan, Richard. The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster. New York: Dell, 1968, p. 103. [Buy at Bookshop]

Celan, Paul. Microliths: Posthumous Prose, trans. Pierre Joris. New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2020, p. 90. [Buy at Bookshop]

Clifton, Lucille. The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton: 1965-2000. Rochester: BOA Editions, 2018, p. 262. [Buy at Bookshop]

Creeley, Robert. The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 140. [Buy at Bookshop]

Hughes, Langston. The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. New York: Knopf, 1994, p. 31. [Buy at Bookshop]

Justice, Donald. New and Selected Poems. New York: Knopf, 1997, p. 47. [Buy at Bookshop]

Merwin, W.S. The Collected Poems of W.S. Merwin: 1952-1993. New York: Library of America, 2013, p. 400. [Buy at Bookshop]

Valentine, Jean. Door in the Mountain: New and Collected Poems: 1965-2003. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2003, p. 25-26. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer