Craft: Voice

Donne, Cortez, Melville, Yeats, Whitman

Voice is connected to tone, which is the poet’s attitude toward a subject. Voice is also related to the psychological state of the speaker, itself a projection of the poet’s relationship to the speaker. Voice is created, too, by diction, which is word choice. All of these dynamics have to be intentional, decisive, discriminatory, and purposeful.

To have voice be meaningful to an attentive “inner ear” during silent reading means that the sound of a poem has to evoke the voice through rhythm. This is Aristotle’s ethos, the thing that expresses the poet’s intention.

When a poet masters the quick control of tone, it increases paradox and contradiction. Poetry is about continuously challenging received assumptions, so the rapid shifts in tone in some poems do the work of pushing through the membrane between the vacuity of the world and the physicality of the world.

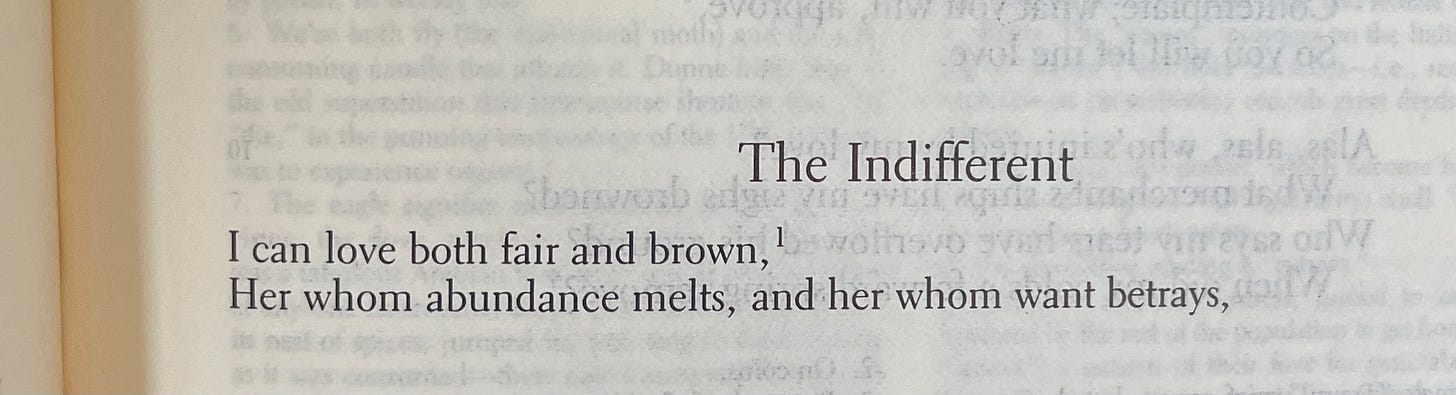

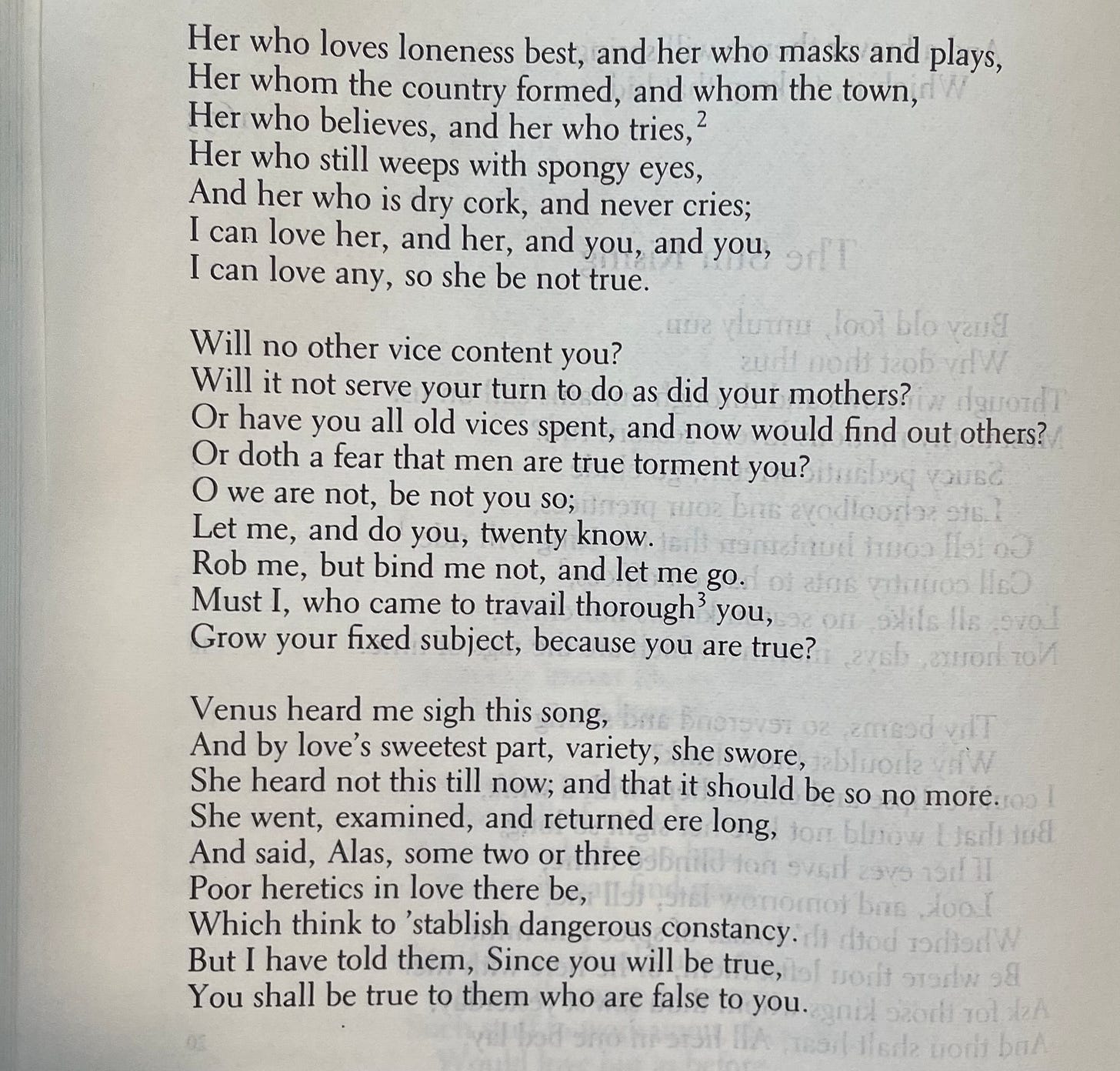

The Indifferent

John Donne’s poem “The Indifferent,” which he wrote in 1633, a year not unlike our own, was a year leavened by tumult and rancor. In February, Galileo Galilei arrived in Rome to stand trial before the Inquisition. He was being charged by anti-science religious zealots to recant his evidence that the Earth revolves around the Sun: his answer was “Eppur si muove,” and yet it moves.

“The Indifferent” begins with the classic romcom conundrum: blond or brunette? The emotive one (“weeps with spongy eyes”) and the stalwart one (“dry cork, and never cries”). The second stanza’s series of five rhetorical questions shifts from the speaker’s certainty to something doubtful, dubious, unknown. The third stanza shifts again to something more distant, the soft sighs of a Goddess who makes a Law out of the unrequited, imperfect, gaunt cinders of love. The entire enterprise is acceptable and clear because of the mastery of the form, and especially, the voice.

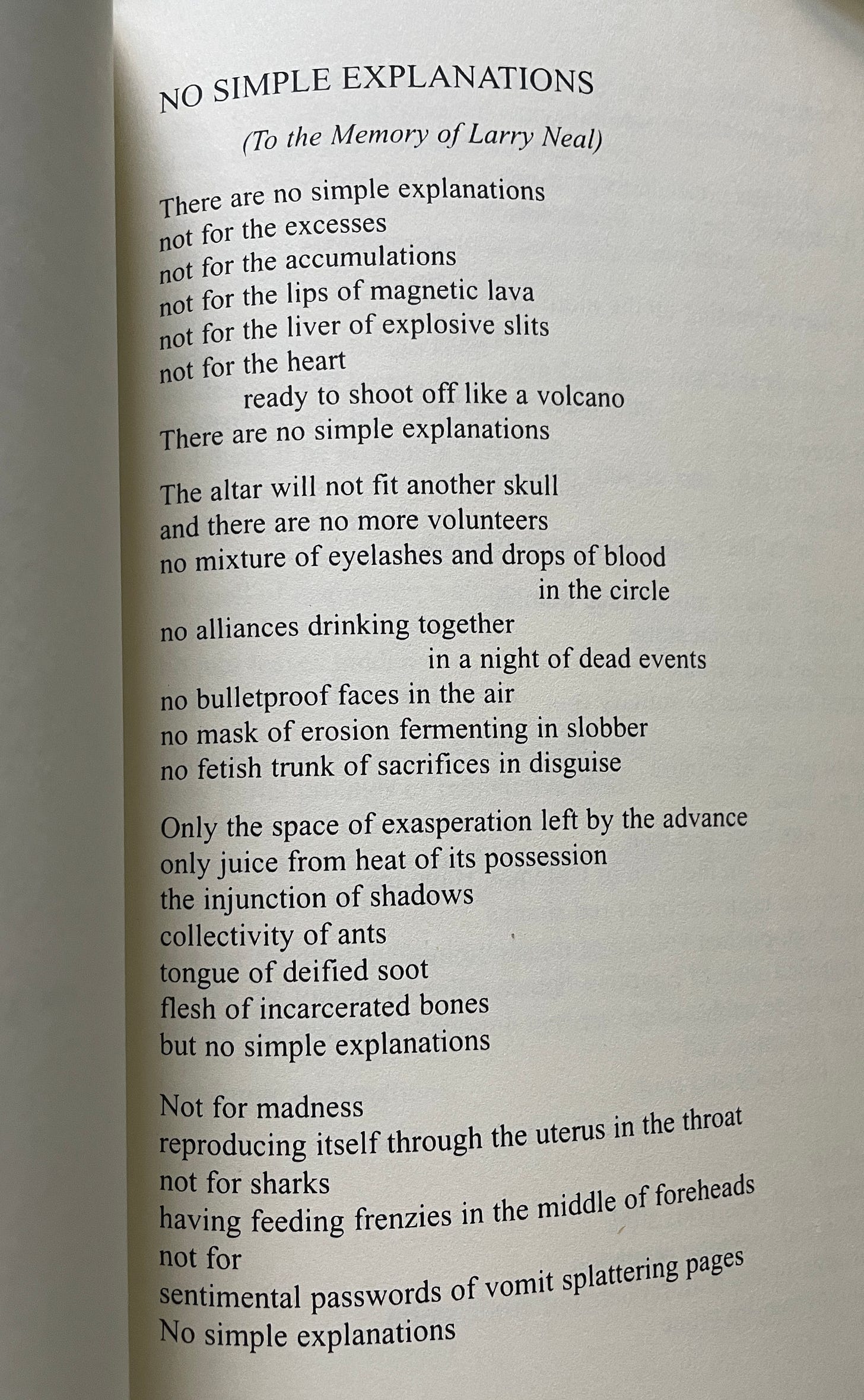

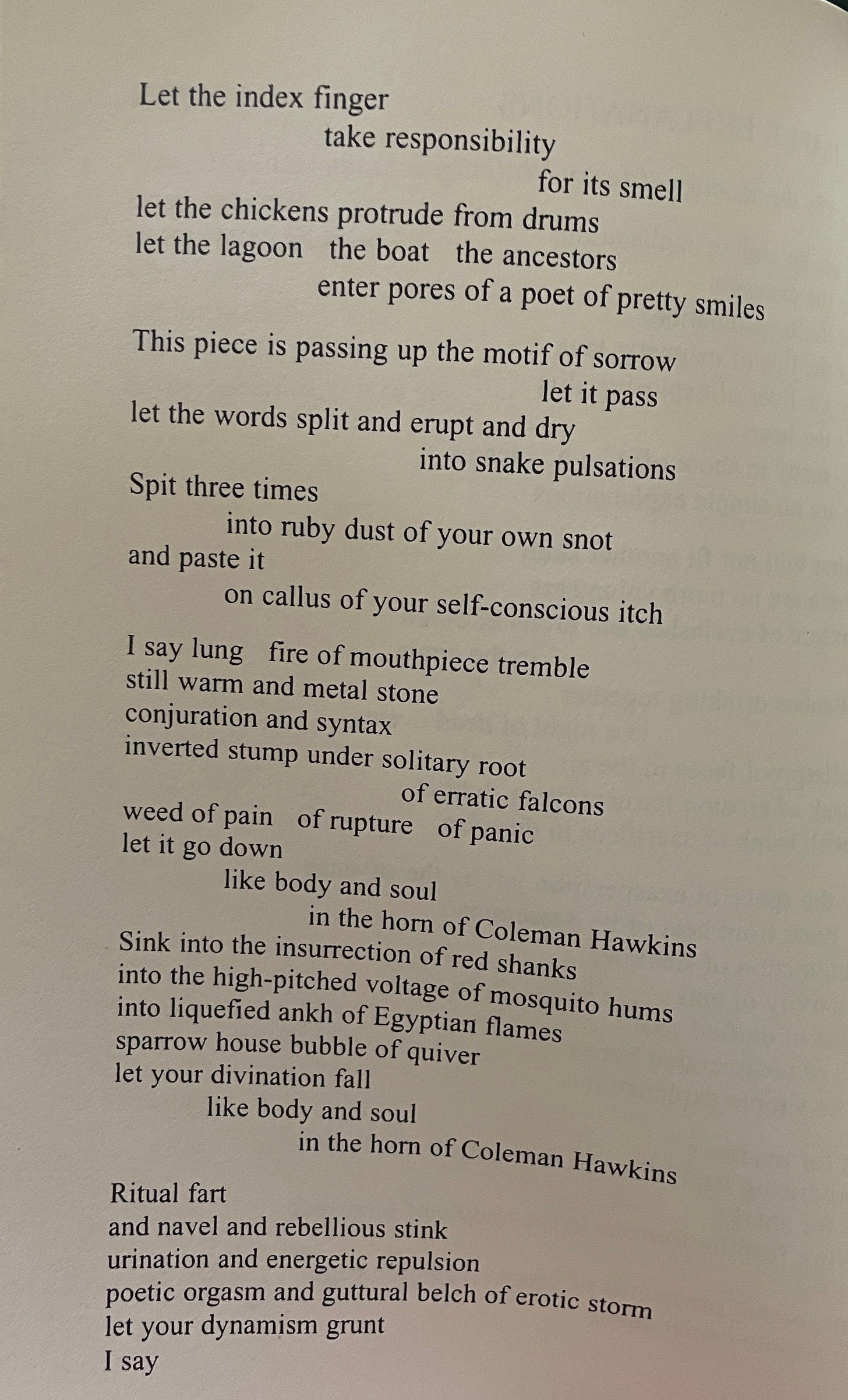

No Simple Explanations

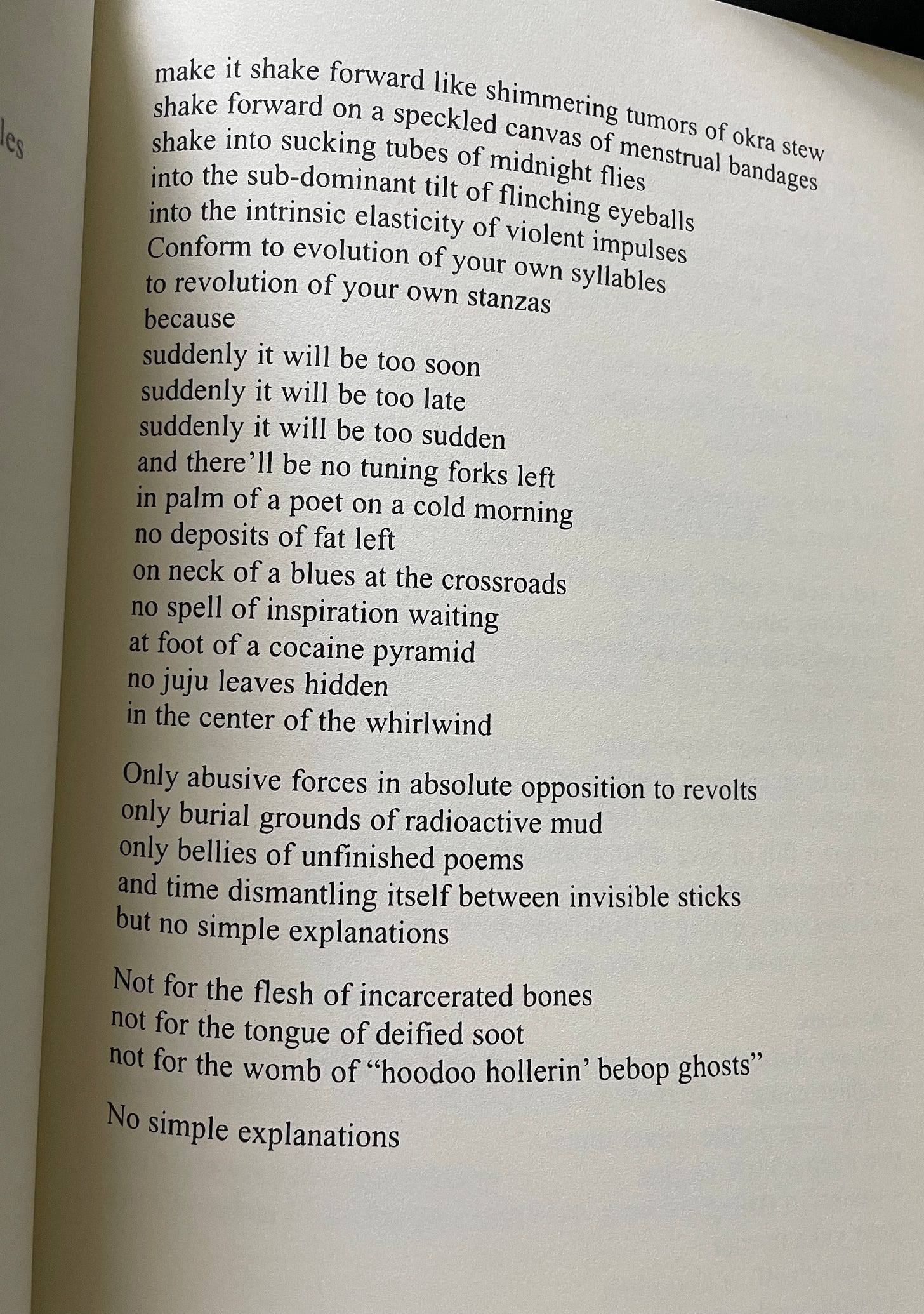

Voice is a manifestation of the poet, and it is presented as a fact of nature, but it is a subterfuge. Listen to Jayne Cortez create her voice seemingly out of nothing in this recording of her poem “No Simple Explanations” with her former husband, Ornette Coleman.

Her voice is an instrument: her ear is an editor and her body is an amplifier. Of this voice and its pairing with jazz accompaniment, Cortez said:

Coleman’s bluesy, astringent tone on his plastic alto saxophone reinforces Cortez’s striking, sacred, monstrous language. The black yeast mixes with oxygen creating this pungent atmosphere: the poem is felt because of the insistence of its voice.

This trenches upon the uncertain

Poems are the bone-like moonlight that reveal what was in the fleshy brain-spawn. There is no home for animal kind beyond the grassy avenues, of dew and sumac on the Earth, and there are no better ways to bring the phantoms we don’t understand into being through the double scales of image and verb.

What binds all these is voice, which is the aim to unify. The voice allows the connections among disparate things or experiences in metaphor to be articulated.

Herman Melville’s statement, “This trenches upon the uncertain and the terrible,” could be the dictum for the poet.

Voice connects to the certain breath to the uncertain word: the poem explores what isn’t said, or can’t be said or explained. Not knowing the answers, but knowing the questions can be a source of liberation. “Radical,” Angela Y. Davis said, “means ‘grasping things by the root.’”

The Lake Isle of Innisfree

But voice must also have a relationship to the poet’s individual obsessions. Yeats’s incantorial voice was necessary to express his obsessions, which were sex and death, and he felt that a serious poet only needed to consider those two things. His recording of “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” was made in 1932. His chanting signals that this is formal verse, and not casual conversation. On some level, his liturgical approach to sound pushes the poem along to the point where it is all-consuming and demands the reader, too, be consumed by the poem’s pitch and push.

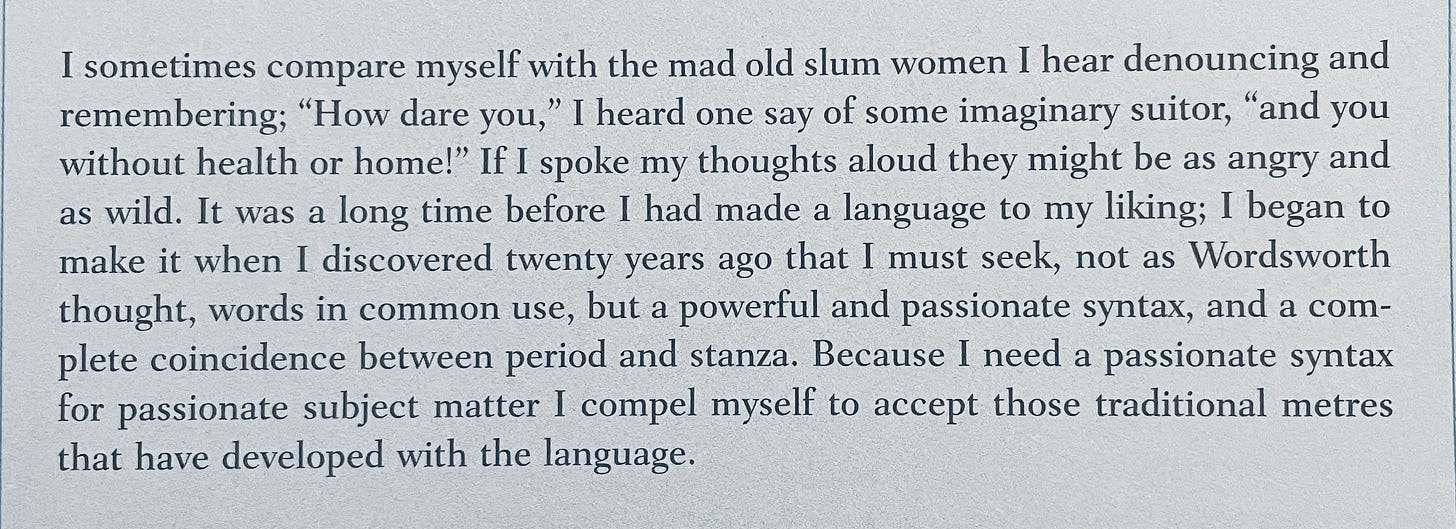

Of his approach to voice, in “A General Introduction to my Work,” Yeats added:

Poetry is not craft. The craft in poetry is only useful insofar as it gives the poet a way to allow their voice to convey the bearing witness of being alive. The voice gives the passionate convictions of the poet a place to reside; the prophecy in a poem brings the poet’s personality and their observed reality into a glass where their liquids are stirred.

America

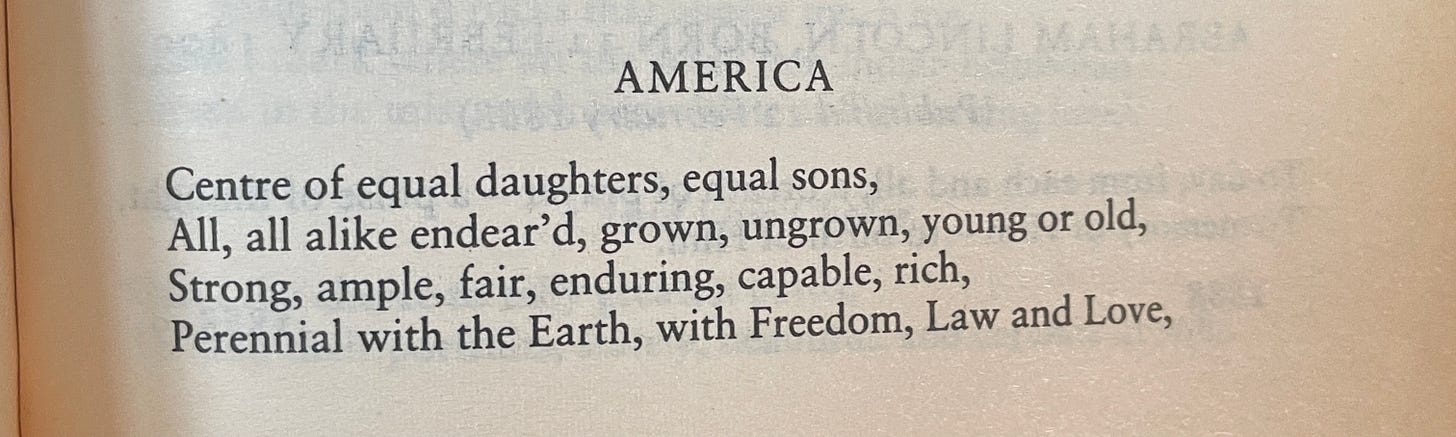

Hear the extraordinary recording of Walt Whitman, reading “America,” written in 1888. The recording, made on an Edison wax cylinder, demonstrates the way his voice is a manifestation of both his persona and his obsessions:

Whitman’s vision of America seems misguided, given his own experiences during the Civil War, which is ongoing, as we must all endure the collective, purgatorial descent into the wounds. Nobody knows what will happen.

Poems are not sanitary texts to be decoded; they are not about knowing the answers to anything. Poetry is about questions, unknowing, and the unknowable. Voices can be certain of their own expertise, but ultimately they are vehicles for the receiver of the poem to have a physical element with which to endure the descent.

For further reading:

Cortez, Jayne. Jazz Fan Looks Back. Brooklyn: Hanging Loose Press, 2002, p. 41-43. [Buy at Bookshop]

Donne, John. The Complete Poetry and Selected Prose of John Donne. New York: Modern Library, 2001. [Buy at Bookshop]

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass and Selected Prose. London: Everyman 1993, p. 493. [Buy at Bookshop]

Yeats, William Butler. The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats Vol. V: Later Essays. New York: Scribner, 1994. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

...I do like the statement "poetry is not craft"; defining a poetic "craft" seems powerfully to deny the very obvious fact that if you use different words you are saying something different. It's one of those things that's so fucking obvious it needs to be said again and again. And often, making that choice for what is superficially a prosodic reason IS complex, because weight and meaning--real, practical connotation-- are conveyed by sound and stress in all speech, even (perhaps particularly) that considered the most prosaic. Anyway...