Writing Problems: Beauty

This essay was written in collaboration with Arden Levine.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”—John Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn”

Much of poetry (lately) comes from a place of negation. Poets are often naturally contrarian and deal in contraries, but as poetry becomes more and more aligned with negative emotions—political fears, traumatic experiences, anxiety about perceived or potential catastrophe—it is at risk of losing one its most valued and valuable attributes: the ability to reveal beauty.

Lately, beauty is thought of as a luxury, something that must be earned, or something that has a privileged expediency. In reality, beauty belongs to everyone, intrinsically and incontrovertibly.

Beauty does not mean flawlessness. A poem that meditates on beauty can include, even celebrate, imperfections, undesirables, and horrors. Nor is beauty synonymous in poems with generic statements about gratitude or the speaker’s moral superiority. Yet poetry that is merely a sociopolitical critique tends to be flat, unimaginative, and dull.

Platitudes about “self-care” are not sufficient. Audre Lorde said, in A Burst of Light, that caring for herself was an act of “self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” In so doing, she has made a declaration of war into an act of beauty, a functional and effective expression of the poems’ experience of a sociopolitical moment, a geography of adoration, shock, and strength.

Keats was right that beauty can focus the attention on something human. I like to turn to the following poets and poems for this purpose.

William Bronk’s “Midsummer” for its embodiment of feeling connected to the environment:

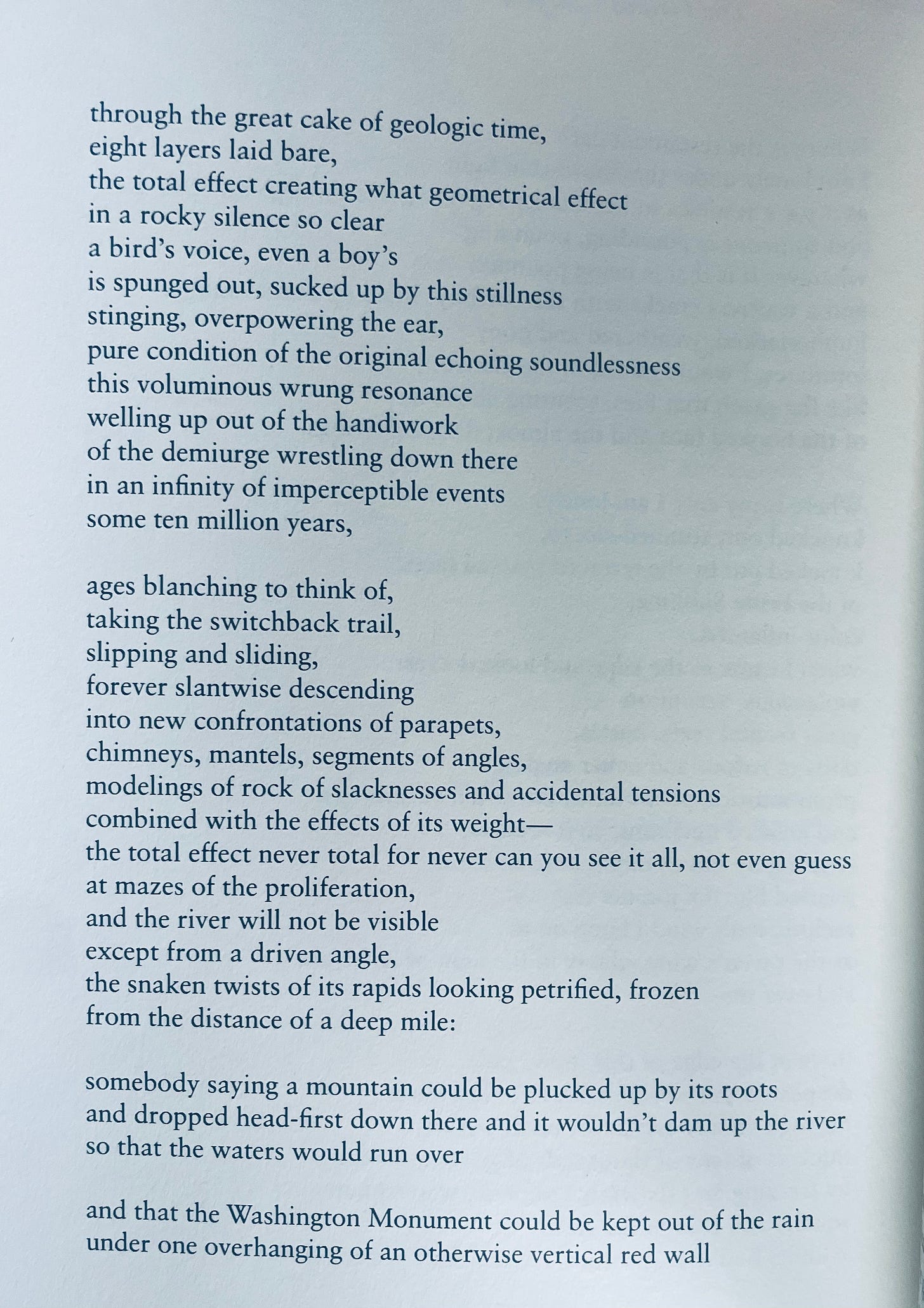

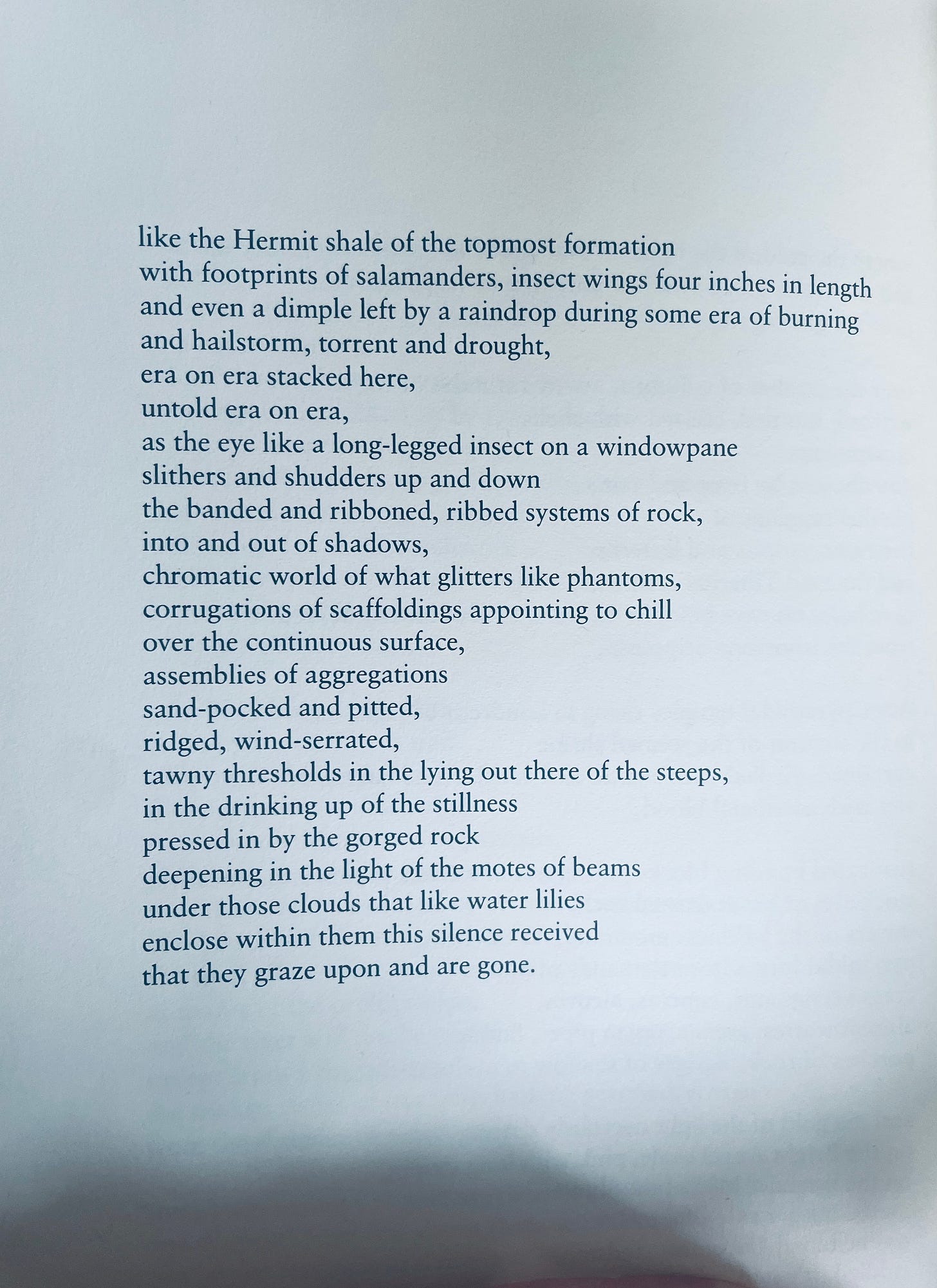

Jean Garrigue’s “The Grand Canyon” for its attention to the telescopic and microscopic at once:

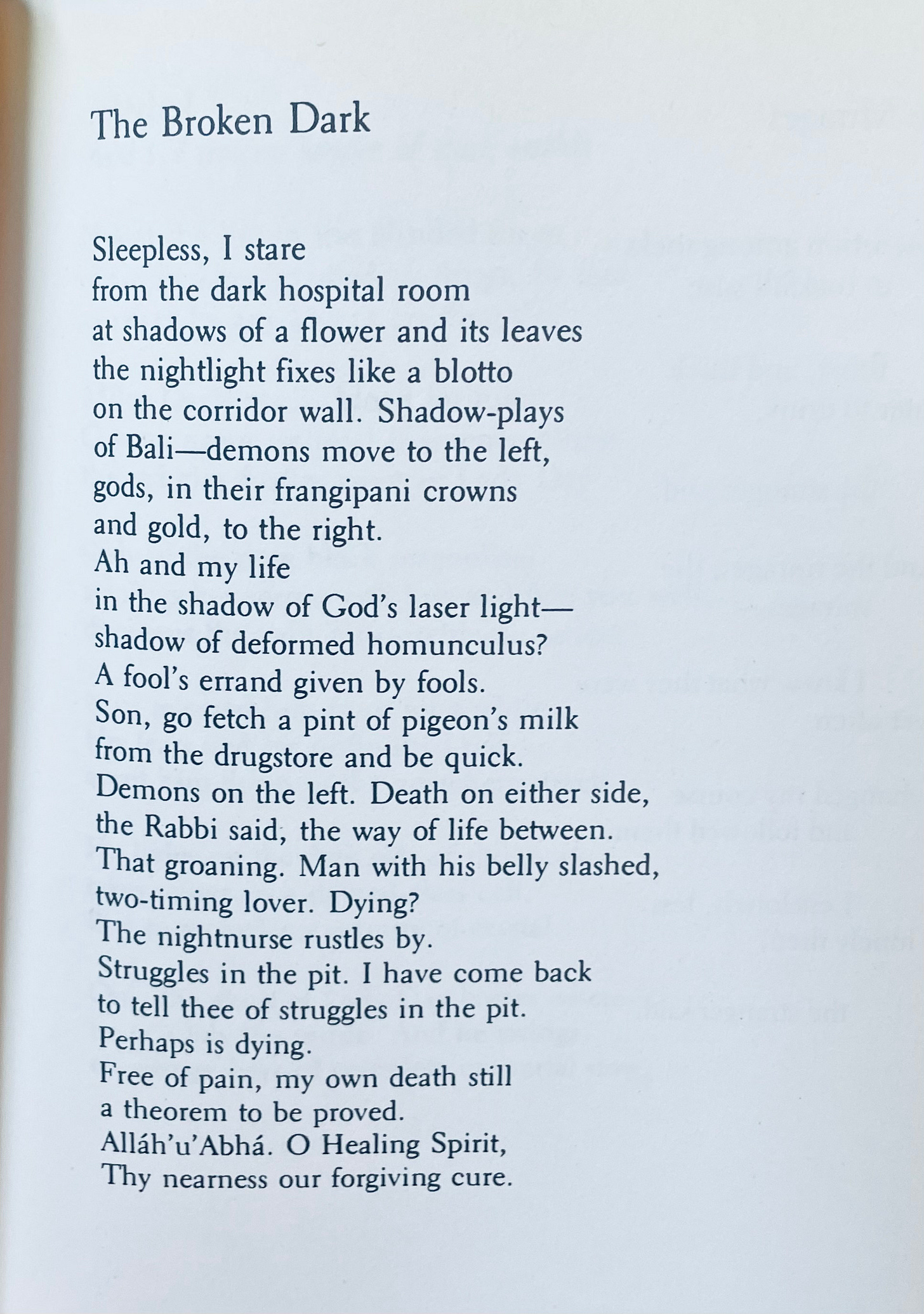

Robert Hayden’s “The Broken Dark,” for its confrontation of our physical limitations and spiritual infinitude:

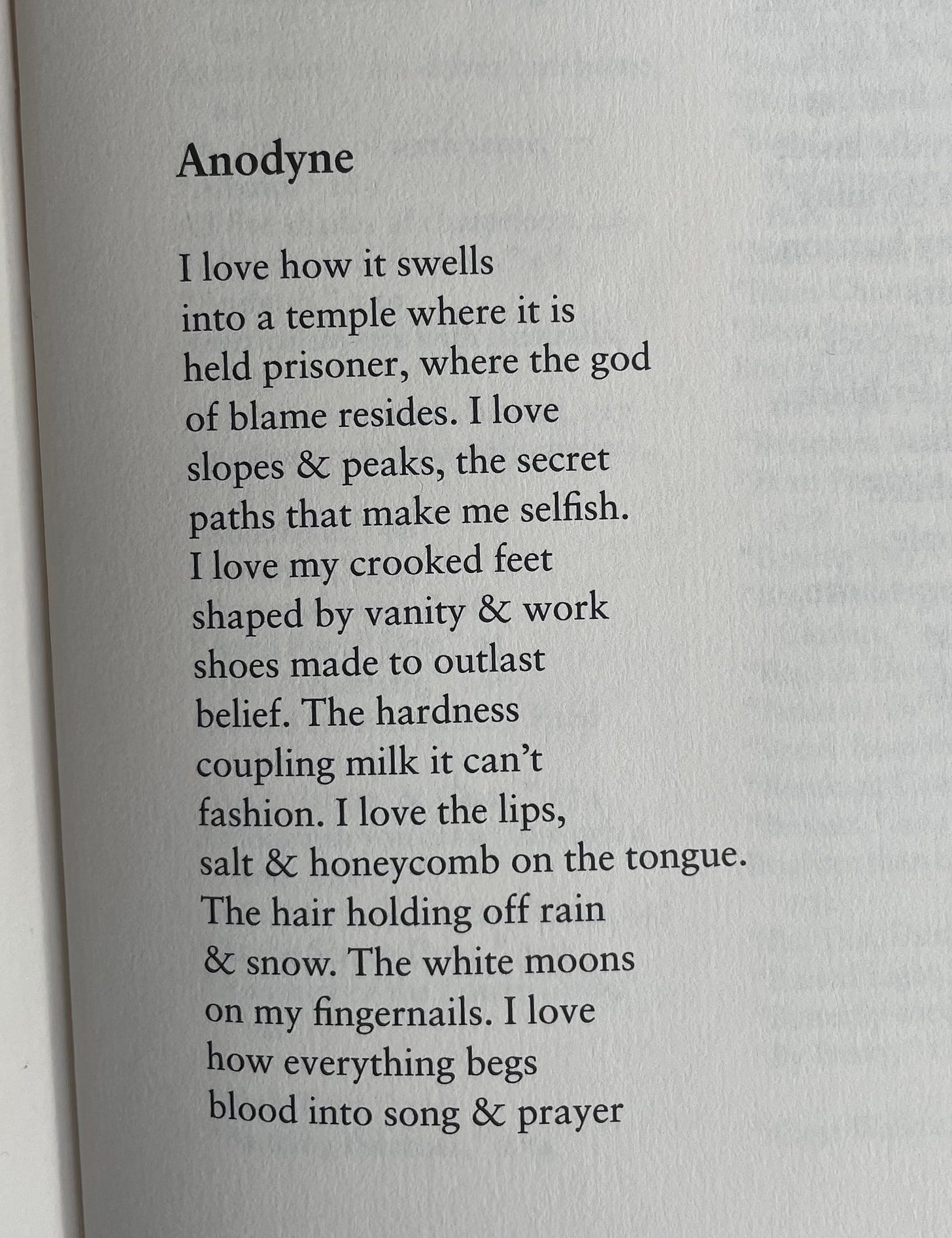

Yusef Komunyakaa’s “Anodyne,” for its unsentimental praise of the body:

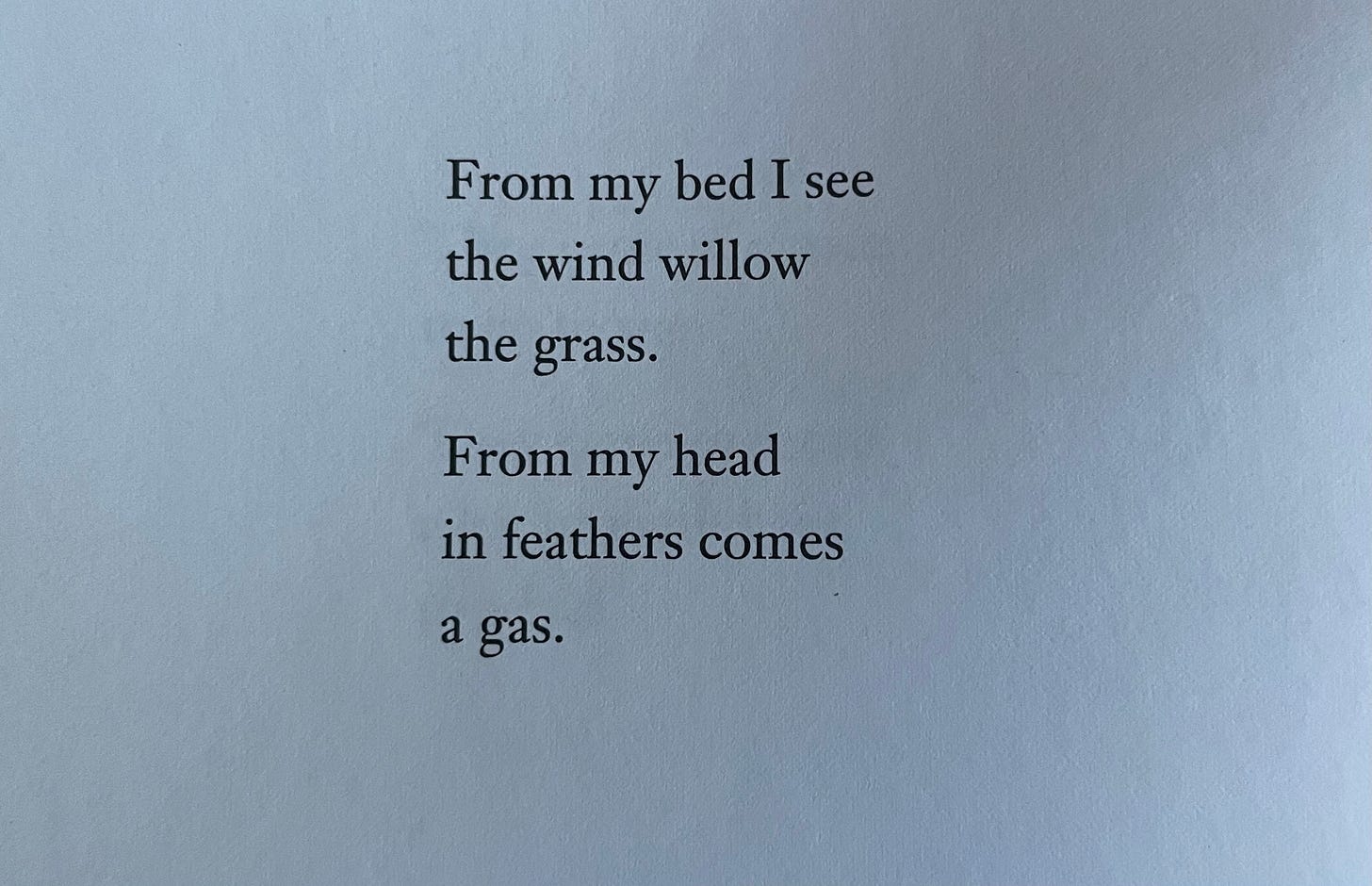

Lorine Niedecker’s “From my bed I see” for its off-kilter rhyme and mix of pleasure and bewilderment:

Wallace Stevens’s “Fabliau of Florida,” for its hymn-like attention to a moment and place:

James Merrill’s “An Upward Look,” for its mastery of placing materiality in empty space:

Kenneth Patchen’s “‘As We Are So Wonderfully Done with Each Other,’” for its full embrace of romance without embarrassment or explanation:

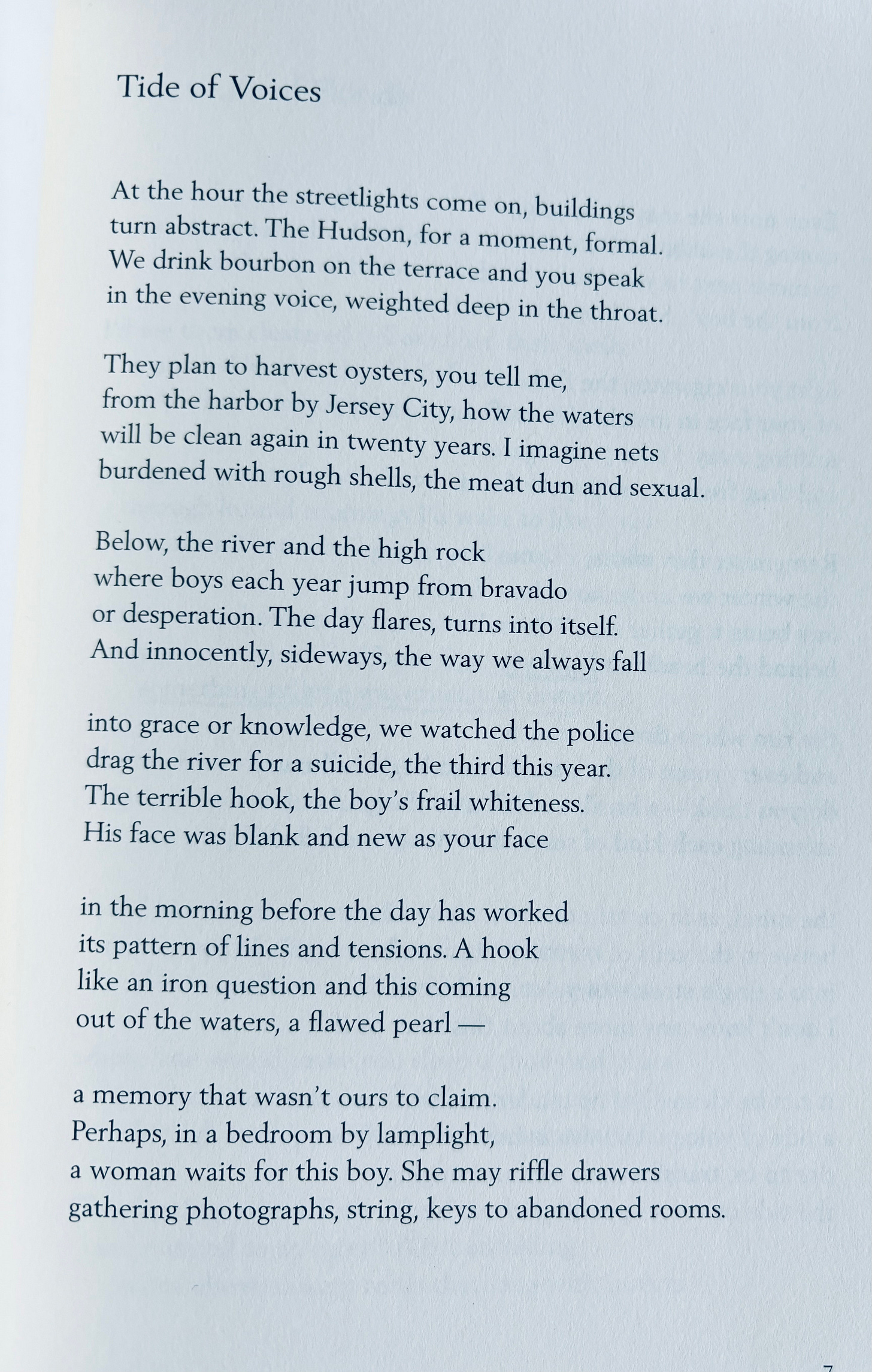

Lynda Hull’s “Tide of Voices,” for its compression of the social, the critical, the celebratory, and the mysterious:

At its best, poetry is about questions, possibilities, the subjunctive, doubt, mystery, clarity, and courage. It’s not about confirming what’s already inside, being complacent, or explaining an idea. It doesn’t argue for a point, it doesn’t need to comfort, and it doesn’t need to be an op-ed. It exists to reveal something, to both reader and poet, that brings us back to a place of awe.

Losing beauty in poetry is a danger. If we focus everything on the loss of freedom, oppression, moral injury, or sickness and lose attention to beauty, then what is all the perseverating for? What are we trying, especially now, to preserve, encounter, and transform?

For further reading:

Bronk, William. Selected Poems. New York: New Directions, 1995. [Buy at Bookshop]

Garrigue, Jean. Selected Poems. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992. [Buy at Addall.com]

Hayden, Robert. Collected Poems. New York: Liveright, 1996. [Buy at Bookshop]

Hull, Lynda. Collected Poems. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2006. [Buy at Bookshop]

Komunyakaa, Yusef. Thieves of Paradise. Wesleyan: Wesleyan University Press, 1998. [Buy at Bookshop]

Merrill, James. Collected Poems. New York: Knopf, 2001. [Buy at Bookshop]

Niedecker, Lorine. Collected Works. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002. [Buy at Bookshop]

Patchen, Kenneth. Selected Poems. New York: New Directions, 1957. [Buy at Bookshop]

Stevens, Wallace. The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens. New York: Knopf, 2011. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

Thank you both for sharing this warning and permission to include beauty in our work. Jean Garrigue’s Grand Canyon is a tour de force that reflects the immensities, complexities, and textures of that place in only four pages. A feat of compression!

Fittingly beautiful and true — and I think this argument could be made for other genres as well. (Playwrights in particular, please read this!) Without light, we can reveal nothing.