Writing Problems: Censoring Maus

Spiegelman, Levi, Morrison

In August I am republishing some of the most popular of previous Saturday essays. Please enjoy.

On January 10th, the McMinn County Board of Education in Tennessee voted 10-0 to ban Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, an important book in Holocaust literature, graphic novels, and Jewish experience. The minutes of the school board meeting show how racism is dull, unimaginative, and dangerous.

Art Spiegelman, after reading the minutes of the meeting, said he got the impression that the board members were asking, “Why can’t they teach a nicer Holocaust?”

Consider these excerpts from the discussion preceding the vote.

To describe Maus as “stuff” and to object to the historical fact that 1.5 million kids werekilled reveals a dangerous way of thinking: that history us something that exists to make Tony Allman feel comfortable, or that history can be reconfigured to confirm his beliefs.

The school board was more concerned with children reading a couple of “swear words” than about the Holocaust itself. They wanted a sanitized version of it, and were happy to ignore the truth. They certainly seemed unfazed by the relationship of book banning to the Holocaust.

Another board member, Mike Cochran, said:

This is one of the “naked pictures” to which Cochran refers:

Imagine the mentality it takes have to object to eighth graders reading Maus because of the “naked picture” shown above. I can see the argument for protecting very young children from the horrors of the world, so they can have preserve their innocence a little longer, but this is not that.

Children live in daily relationship with monsters. Children live in a world where they have no control, and everything is decided for them. So our desire to protect kids is really about our desire to distance ourselves from what makes us uncomfortable. What’s really behind banning Maus is white supremacy.

It’s not just Maus. Republicans are banning books in school districts from Pennsylvania to Wyoming. They’re canceling books—even as they complain about “cancel culture.”

Maus and me

I know 8th graders can and should read Maus, because I was a little younger than that in 1986, when I read it for the first time. I’ve been re-reading it ever since.

Maus was first serialized in Raw Commix. It captured my imagination, and since I was always drawing cartoons, the book’s form opened all sorts of ideas of what was possible in literature. When Art Spiegelman came to give a reading, he signed my copy of Raw Commix Vol. 2, No. 1 in which Chapter 8 of Maus originally appears.

Maus is a story within the frame of another story. It’s about Artie, who is of Art Spiegelman, who is writing Maus. Artie interviews his father, Vladek, a survivor of Auschwitz. Spiegelman’s mother, Anja, survived the war only to commit suicide in 1968.

Spiegelman uses anthropomorphic metaphors (Jews are mice, Germans are cats) to show where three levels of oral history collide: the Holocaust of Vladek’s memory, the relationship between Vladek and Artie in present-day Queens, and the telling of Mausitself. Family tales and tales of the Holocaust converge: both in the way the books are drawn and the way they use layers of history.

When Spiegelman’s metaphor is disrupted, the frames are also disrupted. For instance, when Vladek attempts to escape to Hungary, he is discovered by the Gestapo who remove his cat mask and see he’s really a mouse; they effectively destroy the metaphor. The serrated edge of the frame expands beyond the square into the silhouettes of mice being marched to Bielsko-Biała.

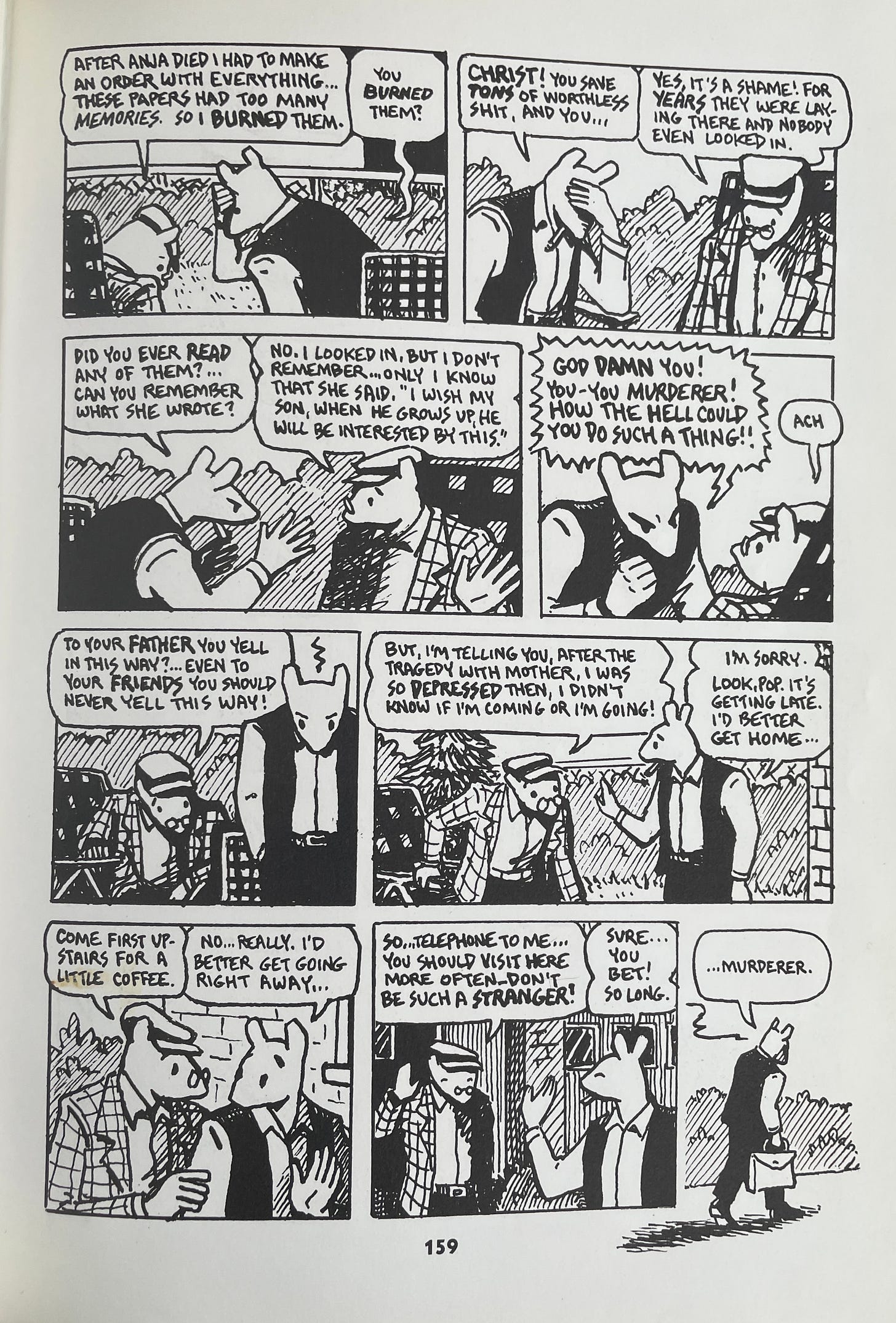

The final panel of Maus shows Artie—again, breaking the frame—walking away from Vladek and calling him “murderer”. The fact that the frame is erased shows the link between two time periods and two metaphoric levels. By accusing Vladek of murder for destroying Anja’s diaries, Artie is connecting his father—via Anja’s suicide—to the war itself. Thus, the violence and memory of the Holocaust is perpetuated beyond Vladek’s life into Artie’s.

The swear words that upset the school board appear in the second and fourth panels: respectively, “shit” and “God damn you!”

What is antisemitism?

Antisemitism is racism.

Race is not real. It’s a construct and serves the function of maintaining white supremacy. Jews make up less than one-fifth of one percent of the world’s population (0.19%, or about 15 million worldwide) yet we have an outsized place in racists’ imaginings.

In America, race is often thought of as a Black-White binary, and Jews fit in neither group. No one seems to know where to place us: the right considers Jews to be non-white, and the left considers Jews to be white. Yet, five thousand years of diaspora means that there are Jews of color all over the world.

The ontological slipperiness—What’s a Jew? Who’s a Jew? “You don’t look Jewish!”— makes it easy for people to project any number of things onto Jews without any logic or coherency. And this happens on both the right and the left.

The people who march chanting “Jews will not replace us!” imagine that Jews are at once subhuman, but also in control of the world financial system.

People on the left often conflate Israel with Jewishness: they’re not the same thing. Being Jewish does not confer responsibility for, or support of, Israel. Or they think all Jews are rich, so Jews must be responsible for the class system and income inequality.

The English writer and comedian David Baddiel had a perfect response to the “Unite the Right” crowd.

Invisible antisemitism

It is easy to look at the Charlottesville marchers and say, “Well, I’m not implicated. I’m progressive. I voted for Obama.” However, banning Maus is what happens when antisemitism is not considered to be a form of racism, but instead as some sort of more acceptable, lesser form of religious discrimination. Would the Nazis spare me because I’m an atheist? Racism is racism.

Jews killed in the Holocaust were not killed because of religious practice. They were killed because they had Jewish great-grandparents who had Jewish children, who themselves had Jewish children. Jews were killed because they existed.

Antisemitism is naturalized into contemporary American culture. Antisemites don’t get cancelled: Mel Gibson, Gary Oldman, Alice Walker, and Ice Cube are still doing their thing and almost no one objects. Nor is anyone all that concerned with the issue of “Jewface,” the practice of non-Jewish actors playing Jewish characters in films and television.

A few recent examples of Jewface: J.K. Simmons as Lenny Turtletaub on Bojack Horseman, Al Pacino as Shylock, John Turturro as the rabbi in The Plot Against America, Helen Mirren as Golda Meir, Felicity Jones as Ruth Bader Ginsburg in On the Basis of Sex, Rachel Brosnahan as the Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. The problem is that non-Jewish actors perform Jewishness: it becomes caricature.

Either representation matters, or it doesn’t.

To take social justice seriously means to understand a few things: antisemitism is racism. Antisemitism is not limited to people who admire Hitler—it has a casual acceptance that often goes unremarked.

It’s not even limited to this planet. Or this reality. For example, look at the Gringotts, goblins who run the bank in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or Quark, the Ferengi, an extraterrestrial race stereotypically only motivated by profit, in Star Trek Deep Space Nine:

Mustard: what should poets do?

Writers have a moral obligation to collect the molted scales of the past. This is to take the snakeskin of history’s horrors, and to un-shrivel it, integrate it, and make it reappear with slithery precision.

We have to do this because history is not history. Jews remain the the most targeted religious community in the U.S.; antisemitic hate crimes are at record high levels since Trump was elected.

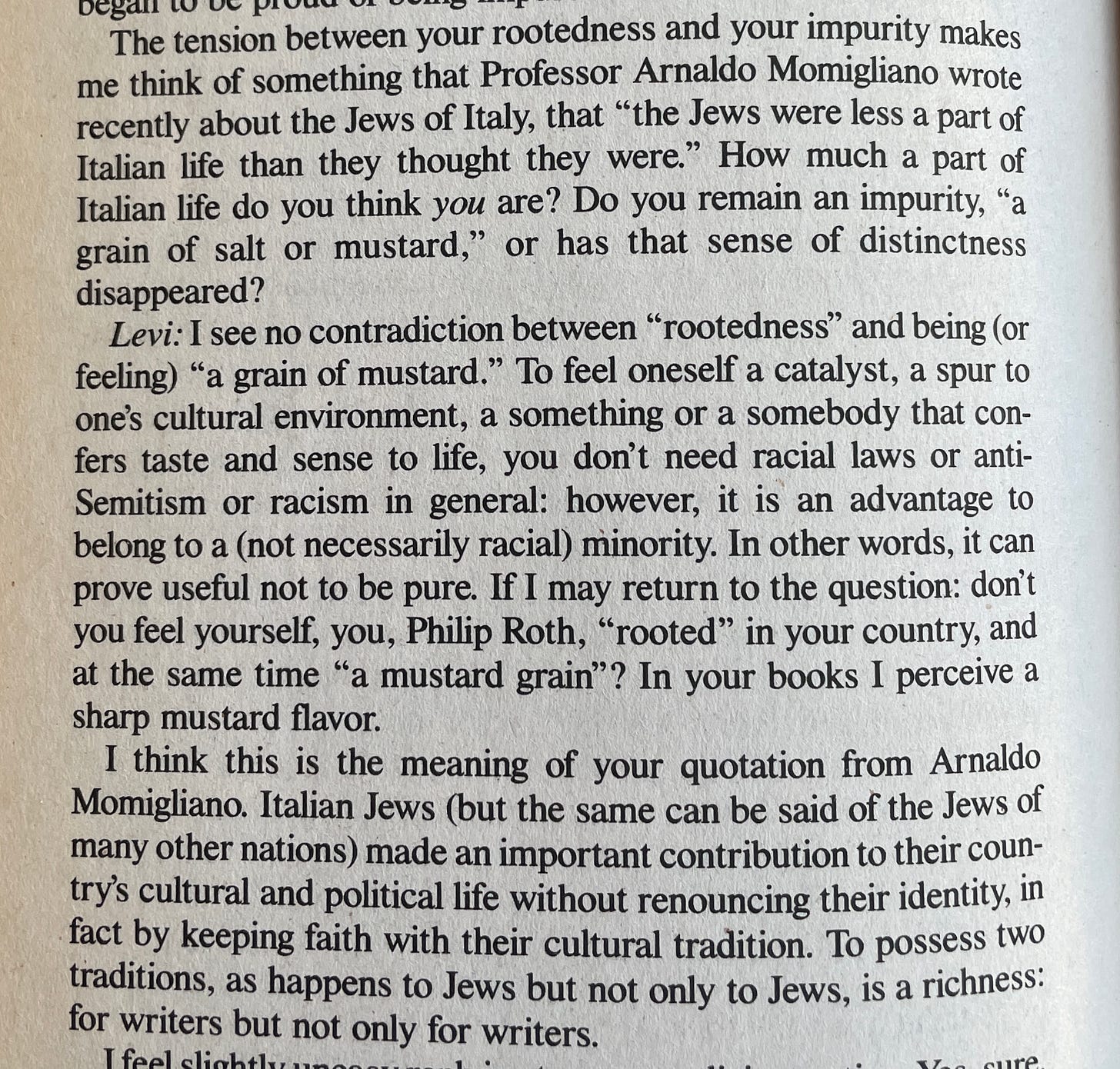

In September 1986, Philip Roth interviewed Primo Levi, the Jewish-Italian chemist and writer. In February 1944, Levi and 649 other people from his town were transported to Auschwitz. Of the 650, he was only one of 20 to survive.

Levi traced his family’s roots back to 1500, when his ancestors went from Provence to Spain to Turin where he was born in 1919. When the Italian fascists imposed racial laws in 1938, Levi’s sense of “rootedness” came up against his being Jewish, which was considered an “impurity.” Levi uses mustard as a metaphor for the odd tension Jews live with.

Levi’s answer—mustard—may also be the correct answer to the racists on the McMinn County Board of Education (a place where 80% of voters supported Trump in the 2020 election), and all the other school board racists. There is advantage to being in a minority. Your “impurity” means you can know the truth; that purity doesn’t exist.

Past or future?

Growing up, I was taught that the Holocaust would never happen again. “Never again” was a mantra I heard repeated many times by my parents, my grandparents, and my Hebrew school teachers. I imagined the Holocaust was a discrete event in the past.

Now, it is clear to me that nothing—no amount of assimilation, no number of degrees, no connections, no amount of good intention—can erase antisemitism. The reactionary forces we see on the school board in Tennessee have always been here, are here now, and will be here in the future.

Jews have survived persecution since the Bronze Age: from the ancient Egyptians, the Babylonians, the Assyrians, the Persian empire, the ancient Greeks, the Roman Empire, the Spanish Inquisition, the Germans, the Soviets. Jews will survive the McMinn County School Board, too.

Writers must stand up to racism wherever we find it. If poets can last through the present—the rise of fascism, Covid, the climate emergency—they will need a new language to write about the experience. That responsibility has to be taken seriously.

Poets need to defend and protect the books that exist and to write the books the future will need. People need books to prepare them to take action, to be citizens, to be aware, and to be vigilant.

There are always going to be people who will object to the truth because without racism, they are not themselves: like Toni Morrison said, the people who practice racism are bereft.

As writers or as non-writers, we must all cultivate our mustardness, to have the moral courage to always be clear about emotional truth, the truth of memory, and the truth of the world of real things.

For further reading:

Baddiel, David. Jews Don’t Count. London: TLS, 2021, p. 50. [Buy at Bookshop]

Delbo, Charlotte. Auschwitz and After. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014. [Buy at Bookshop]

Levi, Primo. Survival in Auschwitz. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996, p. 184. [Buy at Bookshop]

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivor's Tale. New York: Pantheon Books, 2011, p. 58 and 159. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

Sean Singer Editorial Services

Subscribed

Thank you for your writing of Maus and anti-semitism. I care about justice and I want everyone to understand that diminishing other people diminishes oneself.

Thank you for this thoughtful essay! I’m thinking too of my children, who are now one more generation away from the Holocaust, and unlike me never knew personally any survivors. And their father is not Jewish. There’s a yearning in me to find reasons for them to WANT to be Jewish, other than the “we need to survive” (the reason I was given most often, implied if not verbalized). But if they aren’t compelled to continue in some way the Jewish community/identity/culture then what you’re saying is maybe racism/the majority will still consider them Jewish, and thus as Jews they survive. I’m getting a bit muddled. My mom (whose father survived by being hidden by gentiles in a barn in Poland) used to always say it didn’t matter if I considered myself Jewish--the nazis would have rounded me up. I had to apologize to her for my skepticism all those years! She was right that at any moment we might need to run.