Writing Problems: Format

Goodman, Tranströmer, Gilbert, Wright

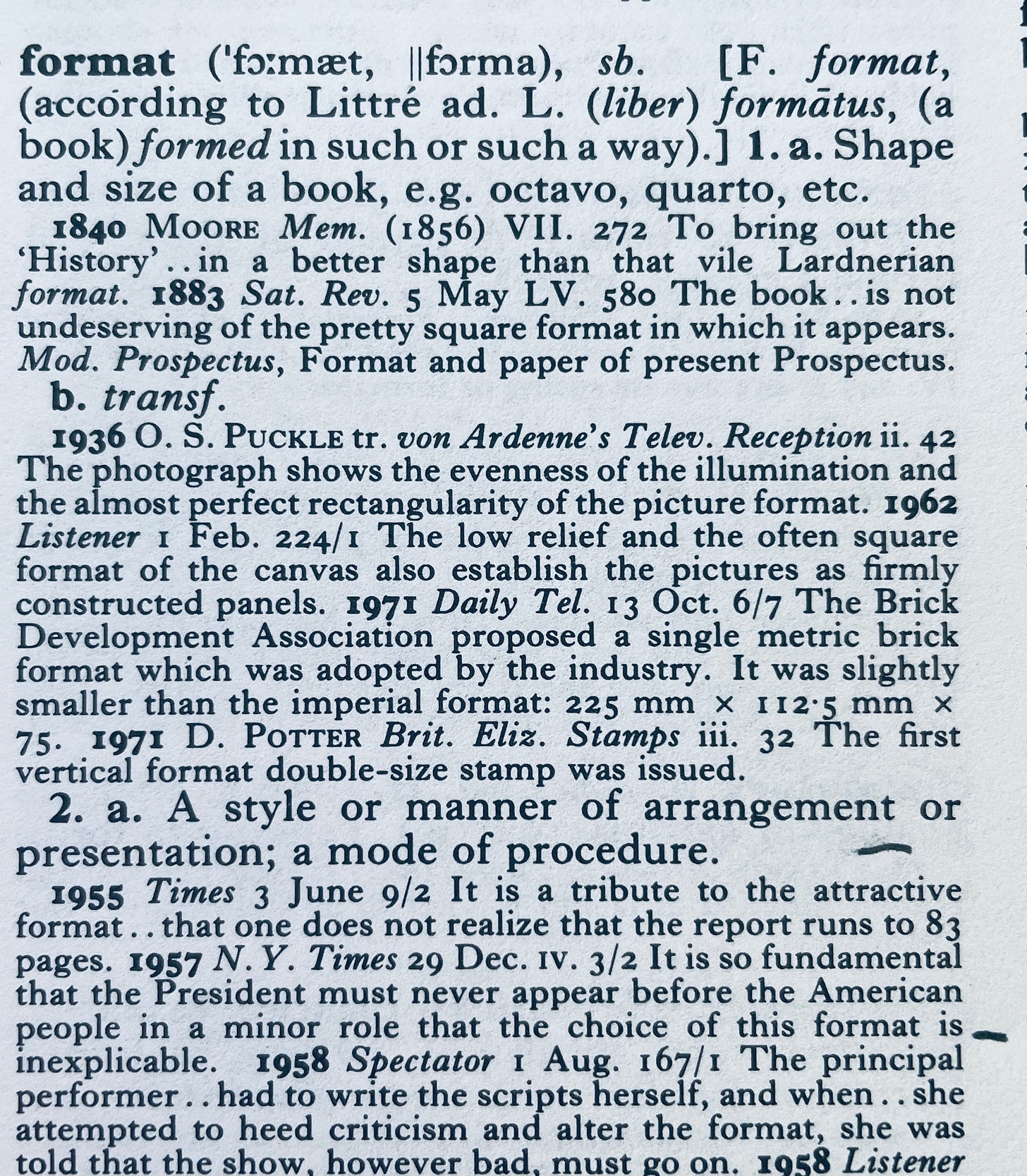

Format is more than just the shape of a book or the shape of a poem on the page. Format is the mode of procedure. It is essentially how the information in a text or in speech is limited and made uniform; the arrangement of its presentation, and therefore, the psychological interface of that information.

Sometimes format exists to impose a rigor or clarity, for example the Chicago Manual of Style. Formats like are useful, but they often make people anxious. When encountering format, it is important to ask is where does it make me anxious, and for what reasons? These abrasions are edges, places where resistance to format is telling you something. This could be an opportunity to push against format.

Writing is not a tool, but an art. This is why formats induce anxiety for many people. Formats are defined structures that regulate processing. Format is important to understand because of its capacity to make controlling speech seem like “free speech.” Format is a powerful political tool because of its demands to reduce, simplify, and flatten meaning. In poetry, freedom is especially palpable because the pulsing anatomy of the self is brought to the surface, where a wading reader can take part of it.

If you value poetry as a way of defining reality, format is key to sharpening thinking. Format means imposing on the poetic process a style that is intrinsic to it. We can’t separate format from our understanding of what a poem is. There are so many institutional, political, and economic structures writhing below the surface that make us feel anxiety, and these are interpreted as formats. Like a cloud of thick sedge, or a sulfurous hail, the implications of political speech on our consciousness is so saturated into our experience, it can be confusing to understand a poet’s responsibilities.

Having discrimination to know where and how to diverge from format throws off not just unsurprising or trite conventions, but an educational system birthed in the Industrial Revolution that would have artists working in toothpaste factories.

Poems are a psychological contract between poet and reader, and because poet and reader are separated in time and space, it is unknowable where they may be coming from. This is why liberation from format is crucial.

In everyday usage, speech in a format is intended to control, reduce, simplify, and implicate. Format is only a way to transfer data, usually for some narrow purpose. Poems explicate what is not said, what is not knowable, what is not understandable. It’s s a fundamental psychological shift from format, which is standardization, conformity, and sameness.

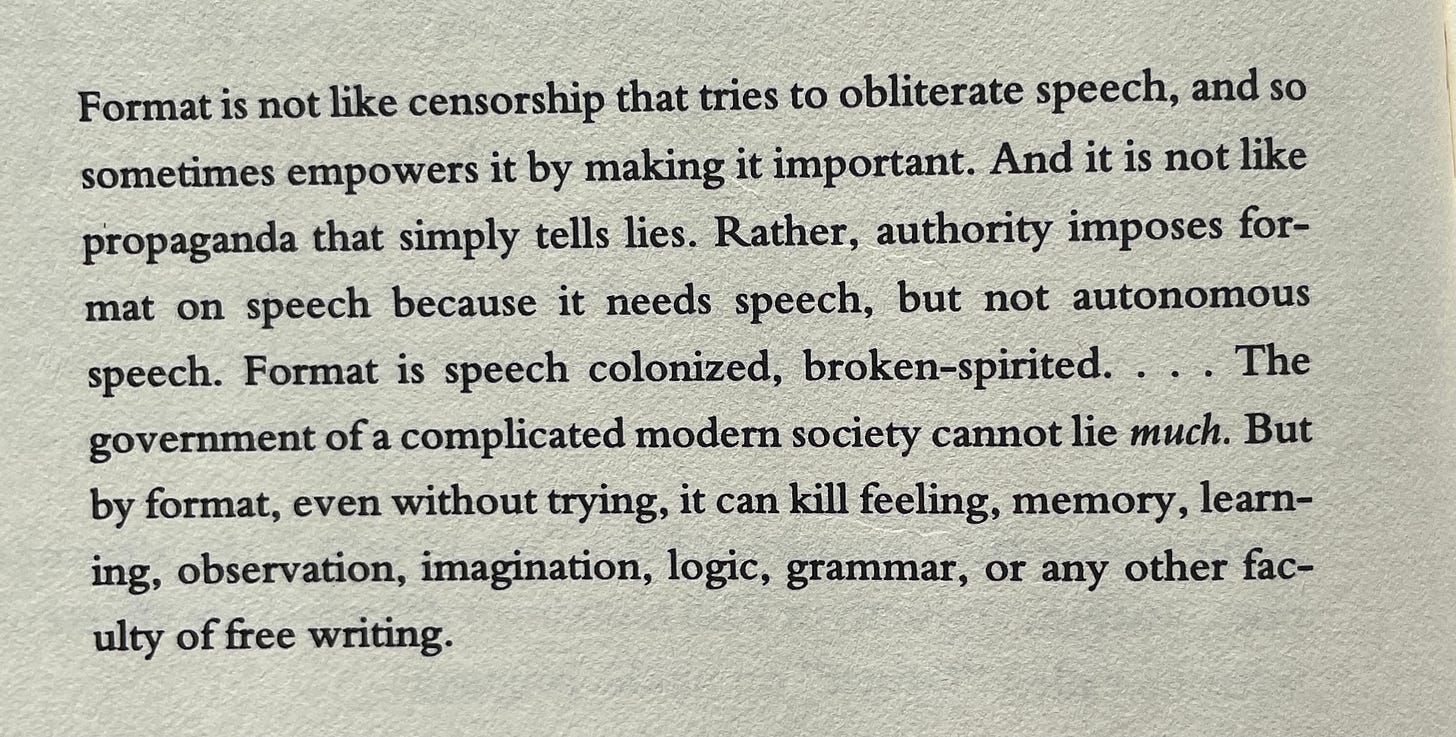

The poet and public intellectual Paul Goodman, was insightful in the ways formats affect writers:

Format is not unlike a soundbite or cliché, a kind of dead language deliberately drained of its blood. Power does not want language to mitigate or assuage. Power insists on a settler colonial definition of freedom, which is to think: my selfish desire is more important than your life.

The ubiquity of the algorithm, as used by Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, is an exponential use of format as destructive force. As soon as a person dips one finger into one conspiracy theory, such as “the Earth is flat,” these algorithms serve up thousands of posts or videos of other conspiracy theories. (By the way, antisemitism is often at the core of a range of conspiracists’ thinking.) Disastrous twilight sheds over many societies now because the giving over of our attention to these algorithms, which are levers of power.

Facebook is responsible for ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, lynch mobs in Sri Lanka, and white nationalism in the United States. Because we are the product Facebook is selling, we are seemingly unaware of the immorality we are brushing against. Underneath the inane animal videos, partisan filth, and idiotic photos of people’s breakfasts, there is a vein of liquid fire sluiced from an endless lake. Zuckerberg—a man who deliberately gets his haircut to look like Augustus Caesar—is now planning a virtual world, known as Meta, so he can further profit by creating an alternative reality because he has destroyed this reality.

Craft

On the level of craft we can create a powerful counter narrative to format. Moving our attention from the naphtha and asphalt garbage spewing from all our devices, we can deliberately choose more spacious understandings of language.

The following are some questions we can ask to expand the potential of poems, particularly in their power to push against or reverse format:

Do my poems have potential to control, destroy, and create social institutions?

Are my poems, to use W.S. Merwin’s term, untrammeled? Untrammeled means a poem’s innate right to freedom

Are politics a subject of my poems or an aspect of my poems?

Do you see poetry as vertical, a place for cultural conflict, or a site where language goes in all different directions at once?

Are you committed to writing that leads to more writing, or are you attached to procedures and results that are likable, sellable, or shareable?

Are these poems susceptible to format, or do they speak freely like an honorable human being?

Is poetry a meritocracy?

How might poetry serve to disrupt and/or reinforce structures of inequity?

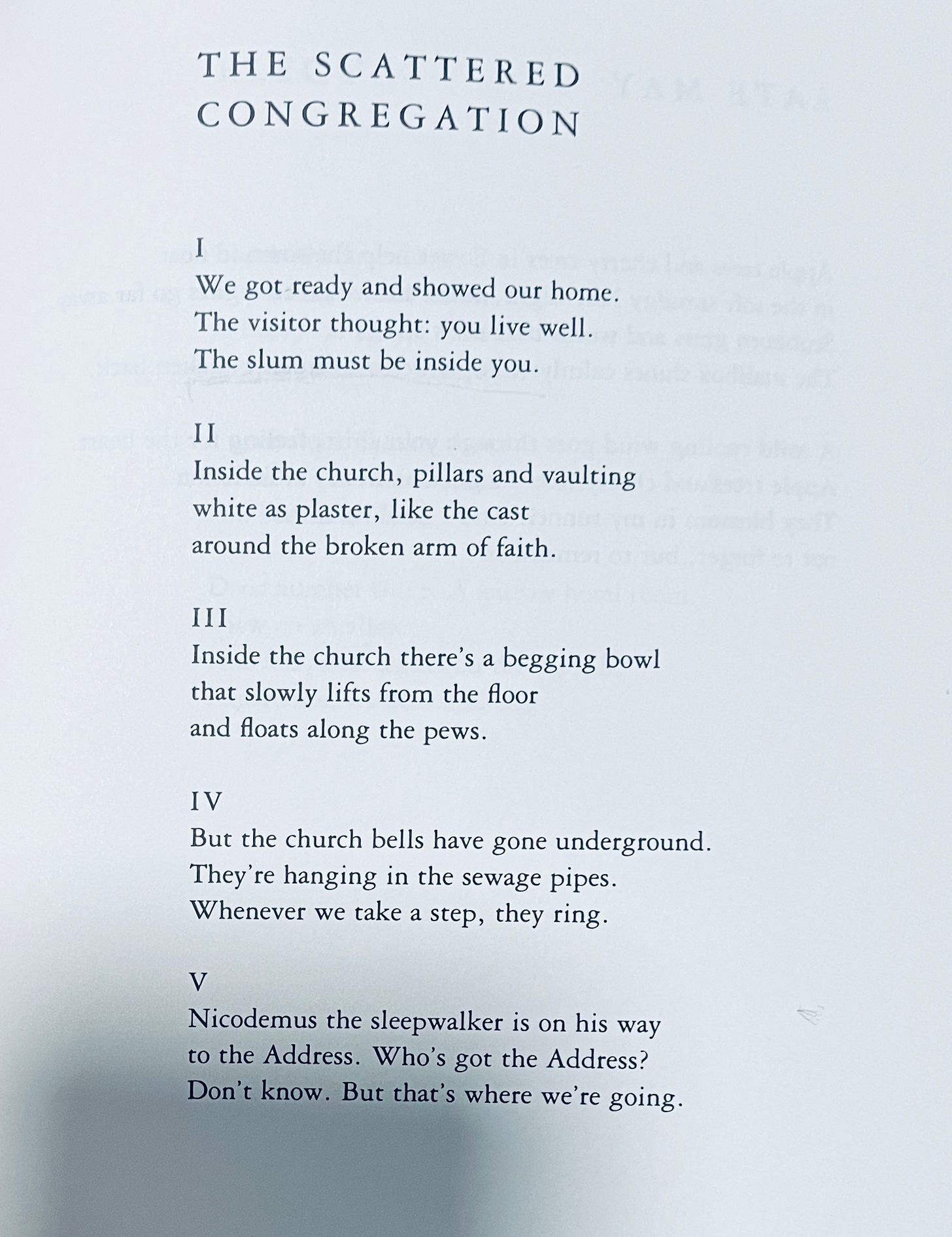

The Scattered Congregation

In the poem “The Scattered Congregation,” translated from Swedish by Robert Bly, Tomas Tranströmer insists on a discursive and liberating poetry that is a journey into extremes:

The third line in each section’s tercet is a little hinge that switches the psychological dimension of the stanza. “The slum must be inside you” means that no matter what window dressing exists, the person’s core cannot be pushed aside or ignored. It may come out in inappropriate ways, but it always comes out.

Formal institutions are merely bandages or plaster “around the broken arm of faith.” We can’t rely of these to restore faith, but only to secure it in place. The bowl for tzedakah, or charitable donations floats along the pews. Good deeds are not necessarily tied to the physical building. But the bells have been transformed into sewer pipes. Finally, we are on our way to unknown destinations. Nicodemus, who normally brings embalming spices and holy powers, is asleep with no known address.

For poetry to be effective, meaningful, and beautiful, the reader has to give into it; in order to get something from it, the reader will approach a poem and not see a door that can be easily opened. A poem may have three gates: folded brass, iron, and adamantine rock. The experience is not the same through each door, but the reader still has to be open to disrupting the code of format.

From this perspective, writing a poem is not unlike talk therapy: the goal is to change the language, change the definitions which are limitations, and to struggle toward new consciousness.

Suffering is often seen as chronic, a miasma that we just have to breathe, because that’s where are lungs draw air. Jack Gilbert said that poetry helps us to suffer more efficiently. Being attuned to the viciousness of empty format can help us chisel and forge a new paradigm: if a stone at the bottom of a lake had eyes.

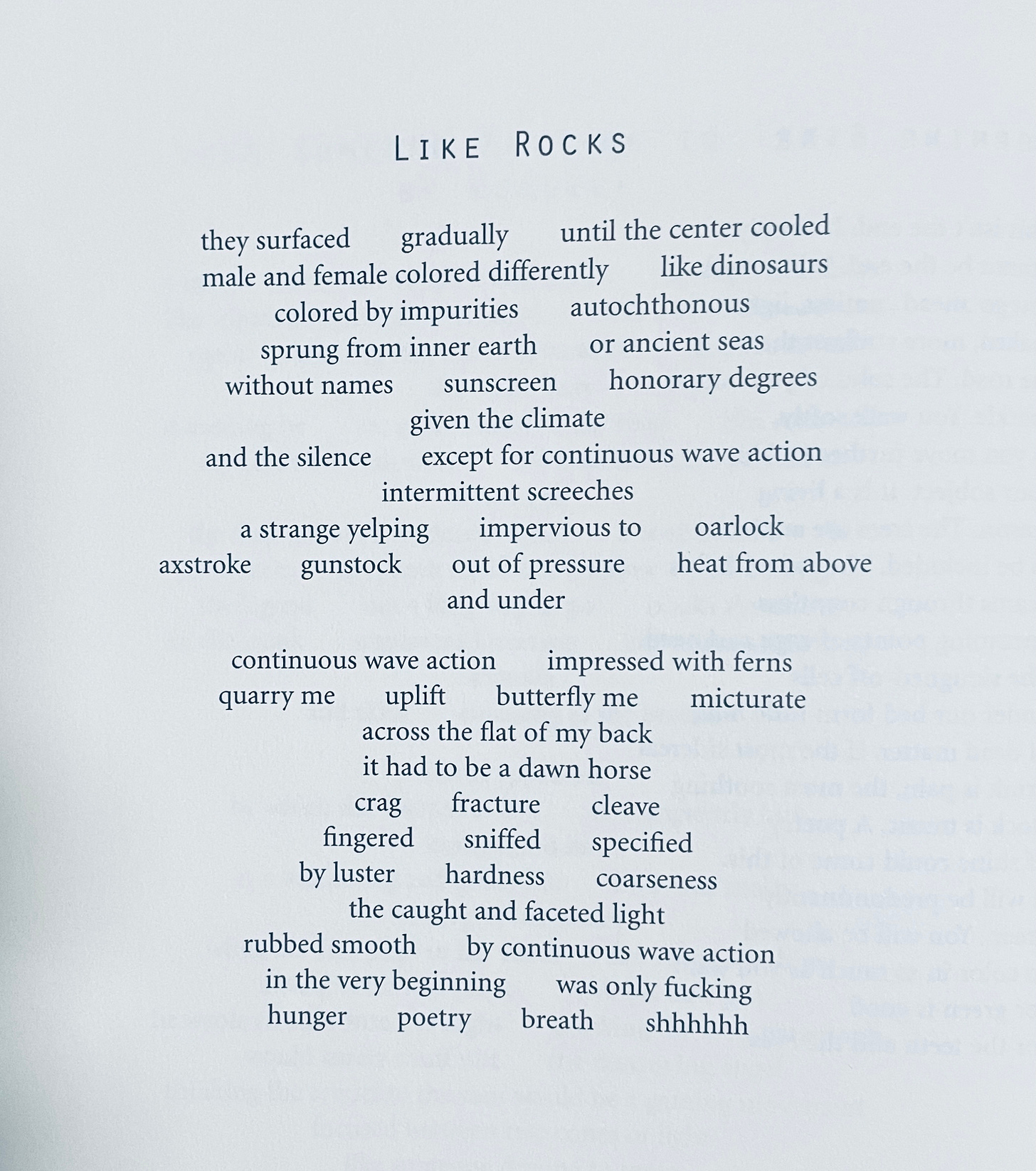

Like Rocks

C.D. Wright was deeply committed to the roots, carcasses, and hosannas of her local origin: the Ozarks. All of her language was empurpled by it—the worlds she created was like a balanced orb that contained everything, but was always saturated by place.

Her poem, “Like Rocks,” demonstrates a wasted and wild freedom from format. Her language is the language of intensity:

By being conscious of format, a dull thing that corrupts and deadens poetic power, we can better harness the wheels of all the psalms and poems that have come before, knowing that the poems we make now will fold into the stream. Marble air, groves, green mounds: the landscape of poetry is more real than real. That is its purpose, but first comes the resistance to format which censors poetry before it can be born.

For further reading:

Goodman, Paul. The Paul Goodman Reader. New York: PM Press, 2011, p. 183. [Buy at Bookshop]

Tranströmer, Tomas. Selected Poems. New York: Ecco, 2000, p. 117. [Buy at Bookshop]

Wright, C.D. Steal Away. Port Townsend, WA, 2002, p. 180. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer