Writing Problems: Origins of Open Form

Conventional wisdom says that open form lacks a structuring grid, does not have meter, and uses grammatical breaks and not rhyme (at least end rhyme). The initial loosening of metrical forms goes back to 17th century France, though what we recognize as free verse (or vers libre) emerged there in the late 19th century.

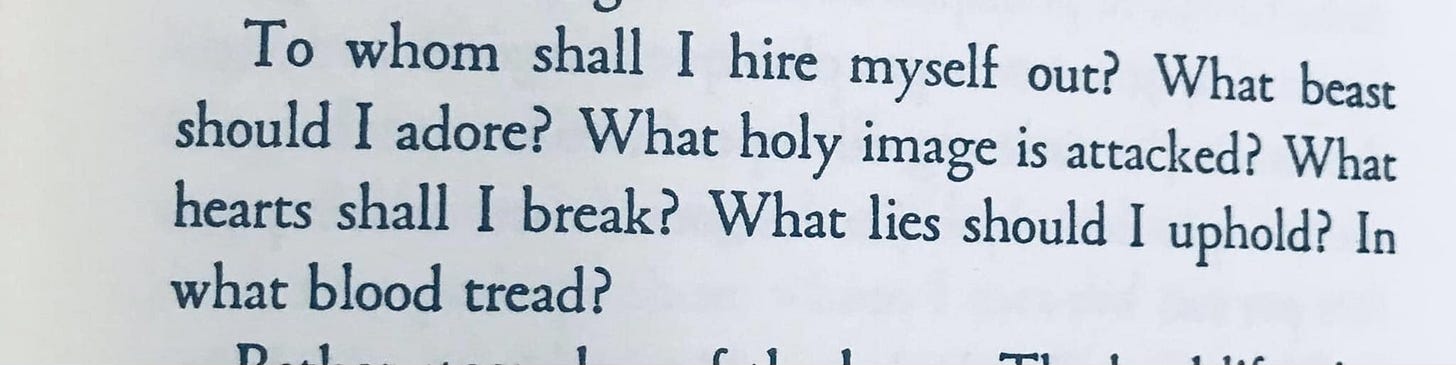

Rimbaud:

In the United States, Whitman’s 1855 Leaves of Grass is the obvious precedent of open form: very long lines; a voice rooted in speech, repetition, parallelism; and an elimination of meter in favor of lines derived from the breath which increased with its list-like construction.

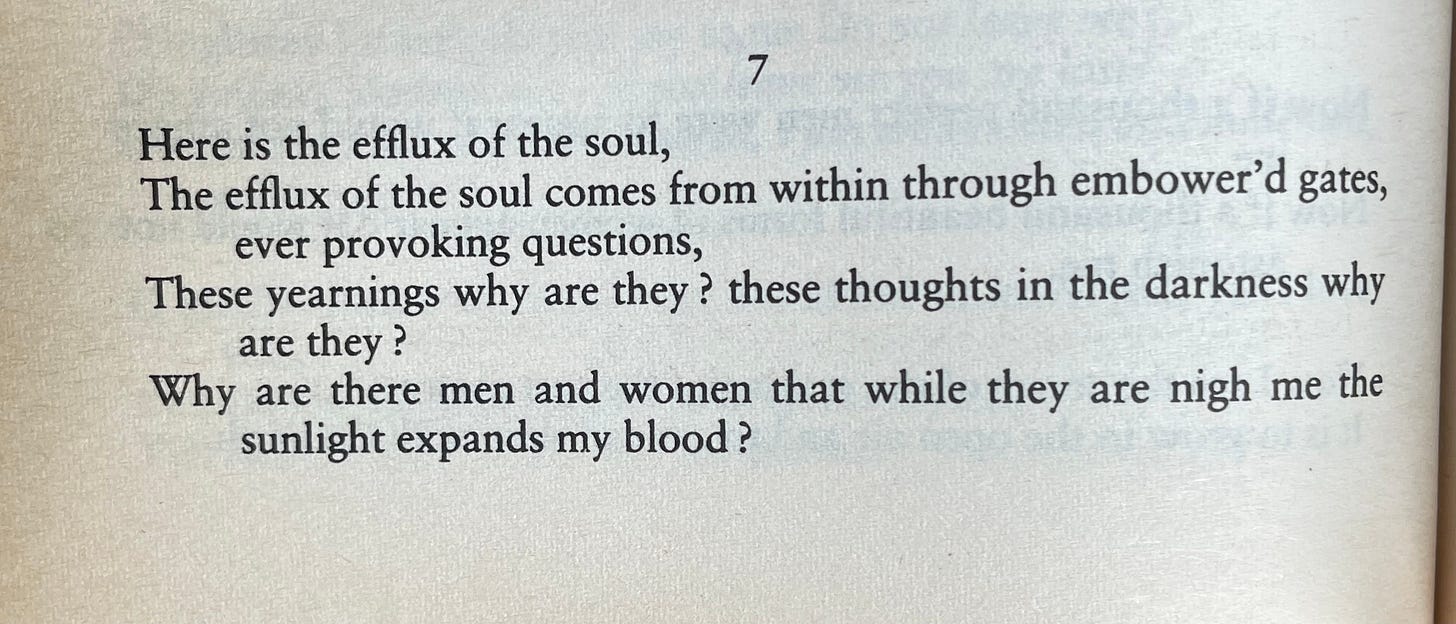

Whitman:

Charles Olson, one of the poets who inherited and expanded on Whitman’s style, said of the roots of open forms, they were a return “to beginnings, to the syllable, for the pleasures of it, to intermit.”

William Carlos Williams’s dictum “Make It New—” to write in plain speech, to measure lines in breath-units, and to use concrete imagery—was not invented in a vacuum. There were numerous progenitors of this style going back to the 19th century.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sharpener to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.