This is a Sharpener that I am republishing for free subscribers. If this content interests you, please consider buying a subscription for yourself or someone you know.

I have conflicting feelings about professional development in poetry. I am by nature noncompetitive and asocial. I don’t like talking about myself, so self-promotion can be a struggle for me. Sometimes I see the business of professional advancement as competitive: a place of gratuitous self-promotion and ego. But I believe in poetry and its difficult, life-enhancing work. I believe that the world is better when more people can write better poetry. When I look at professional development from that perspective, I see it as a place to cultivate mutual cooperation and collective support.

Professional development involves a set of skills that can be practiced and developed. However, the topic of professional development is often glossed over in MFA and PhD programs, where aspiring poets are taught by poets who’ve secured the patronage of jobs in higher education. Too often, our perceptions of the business of poetry are skewed by our limited perspective: we see publications, but not the months of rejections, false starts, stuck places, frustrations, and pressure to accomplish in spite of this, all on one’s own.

Stanley Kunitz said, “The poet's first obligation is survival. No bolder challenge confronts the modern artist than to stay healthy in a sick world.” The rise of Trumpism and the global pandemic shows how the world is both literally and figuratively sick: it is essential that we work together to cultivate this healthfulness.

Platitudes about “self-care” are not sufficient. Audre Lorde said in A Burst of Light that caring for herself was an act of “self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare,” but this radical idea from black feminism has been co-opted by capitalism, as a way to mean just about any part of a cultural hedonism: a date night with oneself, drinking boxed water, doing yoga.

We cannot allow ourselves as poets to be transformed into factories for producing free content for social media companies. Survival as a poet does not mean getting more likes. It does not mean focusing solely on one’s own work. Poets depend on each other for material and psychological support. It’s this exchange of care that marks the poetry community at its best.

I’ve worked on my poems, but have mostly done so outside of any system: I’m not part of an academic institution, have no regular teaching gig, and have been gradually building an editorial services business.

Writing is work. There is also much other unpaid labor which is important to support the writing after it’s written. These cannot be done in a vacuum, either. Supporting writers in your immediate circle is vital to keeping poetry in general afloat. Poetry is also too important to let these things fall by the wayside, or be ignored entirely. Another advantage of this list is to have things to focus your attention on when you aren’t writing, can’t write, or are disinterested in your writing.

The List

The following items are things poets should pay attention to outside the intensive labor of actually writing. I’ve also included resources where possible to help you accomplish the items on the list:

Read at least one book of poetry per week.

If you have the means, buy one book of poetry per week. This site compares prices of all the online booksellers. If you can’t afford to buy books, visit your local library. This directory lists all the public libraries organized by state and contains the physical address and contact phone number for each library.

Subscribe to literary magazines—two or three, at least, if your budget allows. Or, visit your library to read them.

When you read a poem or book that holds your attention, write to the poet to tell them so. You can often find their contact information through a Google search; on their websites; or by direct message on social media.

Be informed about the poetry of at least one other language besides English.

If you know another language, translate poems from that language into English and poems from English into that language. Translation can strengthen one’s understanding of their own language, and it makes more poems available to more people. This conversation with Kimiko Hahn is a helpful resource on the legal and ethical implications of translation.

Have a professional bio for yourself in three versions: 30 words, 75 words, and 250 words. Make this available for download on your website as a PDF with your full name in the filename (e.g. “SINGER Sean Bio”) and your contact information on the page.

Have this bio reviewed by someone whose opinions you value and trust, and who understands the conventions of the poetry world.

Build your personal board of advisors—a group of people who know you and your work; who know your field; and can offer meaningful, unbiased feedback.

Read reviews and offer to write reviews of books of poetry. This gives you a voice in the conversation about poetry; helps to build a readership for the poet whose work you’re reviewing; helps to sell books; and forces you, the reviewer, to sharpen your opinions and insights.

If you write a review, tell the publisher of the book you’ve reviewed.

Share news of others’ publications if you appreciate their work. Praise what deserves praise.

Have an updated resumé. You may need more than one if you’re pursuing multiple goals: teaching, arts administration, or an artistic project.

Have your resumé reviewed by someone whose opinion you value and trust.

Have a website that provides direct access to you and your poetry, and a means by which people can contact you. directly I used Squarespace to make mine.

Have your website regularly reviewed by someone whose opinion you value and trust.

Attend others’ readings when possible. It is tempting to leave a Zoom reading on in the background while you cook dinner, but meaningful participation in a reading involves attention and listening, and telling the reader(s) about your experience afterwards.

Meet deadlines on time.

Find a way to cultivate and engage an audience around your work. If you like social media, use that. If you think social media is utterly destructive, then don’t use it. Other platforms such as Substack or Mailchimp are alternatives for some people. Cultivating an audience through personal engagement shows potential publishers you have a readership. It also helps you build the world around you that you want for your work.

Engage in reflective exercises to check in on your big picture goals.

Keep these reflections organized so that you can review them over time to see shifts in your perspective.

Develop skills of psychological sturdiness. These are some ways to strengthen ourselves so that we can keep writing literature. Carol Bly, in her book Beyond the Writers’ Workshop, lays out five steps: (1) Decide to hear our own thoughts or others’ at all; (2) Empty yourself of your own point of view; (3) Ask people or yourself open-ended questions that enlarge or refine what they’ve said; (4) When you’re listening to others, paraphrase what you’ve heard to make sure you understand it; (5) The empathic listener helps the speaker look forward. The purpose of these skills is to give your own imagination confidence and to make connections that will create metaphor.

Be aware of bullying, especially in the context of writing classes. Use bystander intervention techniques if you see bullying happening.

Be aware of endemic injustice. For example, some writers have money all their lives, ample time to write, and can afford to not be exhausted. Others have demanding jobs, can write only in the cracks between work and childcare, and don’t have the support of partners or nearby parents.

If you are in a position of power, or have cultural capital, educate yourself on how to better empower those who have been deprived of power.

If you are a white man, refuse to serve on panels or read at readings if everyone else on the roster is a white man. Tell the organizers this is the reason you refuse. If you notice an event is excluding people, make the organizers aware of it.

Deliberately keep intact a general affection for the universe no matter how horrible the things you may be writing about. For example, Erich Remarque, Anne Frank, and James Baldwin wrote in ways that preserved their psychological stamina, and did the hard psychological work of describing their circumstances in a clear way.

Each of us has a story that is unique and compelling. In your writing allow for surprising insights that others don’t know about, rather than conventional insights. Trust your expertise in your own life.

Write out your goals and regularly assess your progress. Check in with your goals to assess whether they need to be modified. Rework them continually.

Keep an ideas journal or document where you can keep track of new ideas.

Organize conversations with other people in your network to brainstorm ways you might pool your resources.

Give thought to your artistic goals such as finding the right form for what you want to write about, or writing different kinds of lines than you did in the past.

Give thought to your professional goals such as partnering with a local arts organization to run workshops or readings.

Give thought to what your personal goals are: everything you wish to do outside of poetry.

Look for intersections and conflicts between your personal, artistic, and professional goals. Seek ways to re-balance your priorities at different times in your life.

Arrive at appointments on time.

If you work in an academic department, be kind to the administrator who likely keeps the entire machine running and whose help and work is usually overlooked.

Develop a detailed picture of what you would like your life to look like in 3 years, 5 years, and 10 years. What gets in the way of this, for me, are lack of self-insight, confidence, or instability in some form or another.

After taking an inventory of your skills, understand the things that you struggle with outside of poetry. For example, As you work through this list, take note of the skills you struggle with, in or out of poetry.

Have a plan to address the skills in which you do not excel.

Develop an in-depth knowledge of the economic ecosystem of poetry and publishing.

Develop ideas about how to pursue funding for your artistic projects. The New York Foundation for the Arts maintains a comprehensive listing of artist opportunities and services at NYFA Source.

Understand the lifecycle of funding for artistic programs. Understanding how arts are funded can better prepare you for making a case for why the organizations that fund it should fund your work. Poets & Writers maintains this list of available grants.

Think about ways that you can help others through your poetry. Writing poetry means thinking through questions and being uncertain. It means looking into oneself and bringing something to the page that was unknown before, a dark wilderness you did not have access to before writing the poem. Showing others that they might have a doorway into the self is helpful.

Keep a record of your professional contacts and exchanges. These are people in your network with whom you can trade skills and resources. You can use a yellow legal pad, a Google spreadsheet, or any method that works for you for this record.

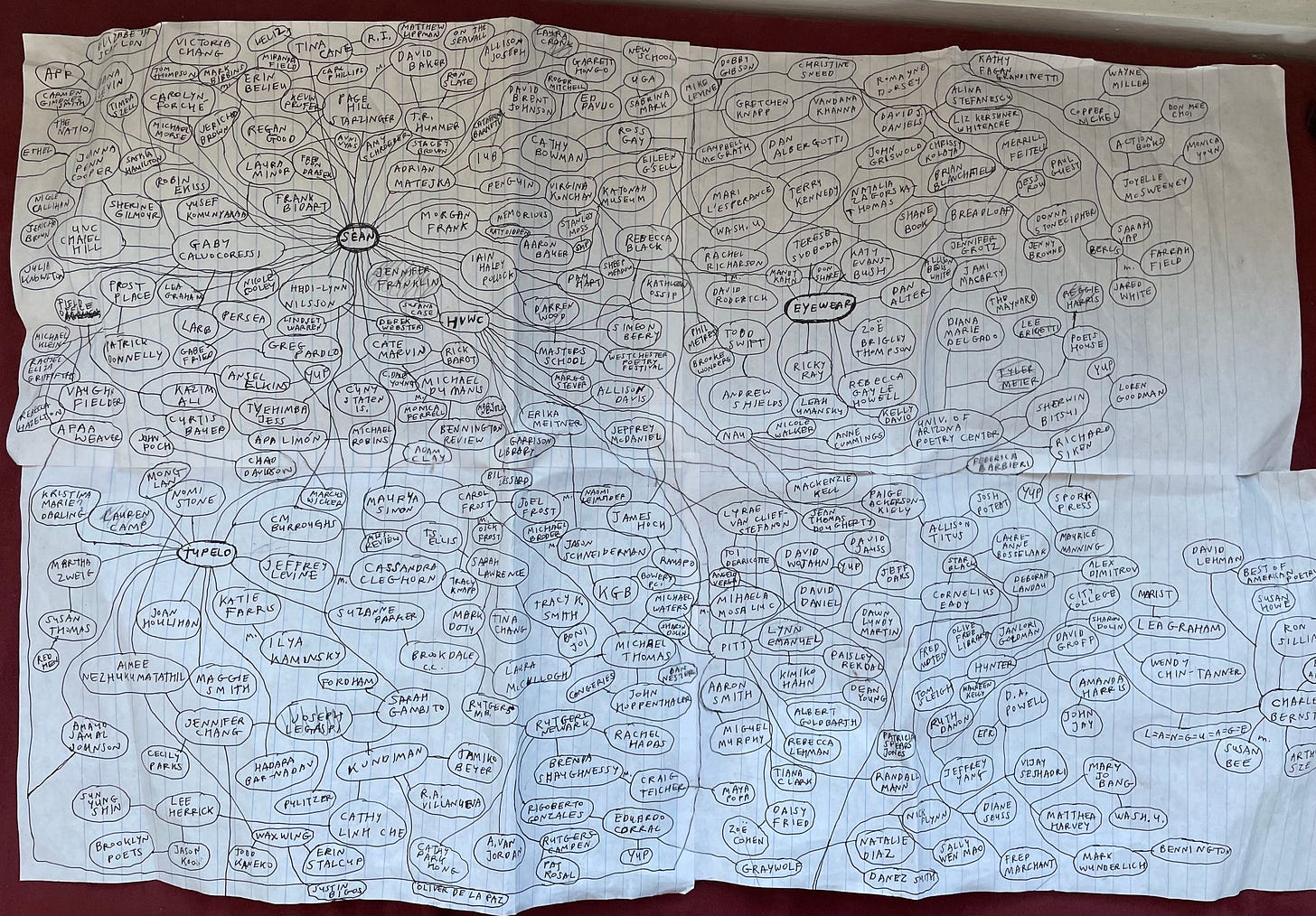

Make a map of everyone you know in poetry and their connections (see below).

Keep your email inbox organized, and respond to messages quickly.

Have an up-to-date professional headshot that represents you in an accurate, attractive way. PR images should be available in both hi-res (300dpi for print media) and lo-res (72dpi version for web use). As a general rule, images should be a minimum of 1 MB (preferably 2-5 MB), 300 dpi JPEG files, measuring at least 1500 pixels at the longest length. Make your images available for download on a “media” page on your website, along with a photographer credit.

Have examples of your poems easily accessible to anyone who wants to learn more about you.

Take account of how much time you spend reading, writing, sending out manuscripts, and maintaining professional relationships in poetry. Then make a time budget that allows you to fit these activities into your life.

Establish a written hierarchy of your personal values, in order to help guide decision making. Here is a list of 50 core values.

Have a basic understanding of general bookkeeping and accounting principles.

Understand what it means to make a case for the value of your work. This should include your mission, vision, and values, and should set out to clearly answer the who, what, and why of your writing.

Have a concise, compelling written artist statement that describes who you are, what you do, why you do it, and why others might become engaged in your work.

Develop an elevator pitch for your current project. Imagine you’re riding in an elevator with your dream publisher: you’ve got 30 seconds to describe who you are, what you’re writing, what it’s about, and why they should pay attention to it.

If someone tries to rush you, practice saying “I’d like time to think about that some more.”

Use a calendar not only to mark important events, but also to establish deadlines.

Keep apprised of postings of jobs and opportunities (such as The Academy of American Poets, Poets & Writers, The Chronicle of Higher Education, or Associated Writing Programs).

Make a spreadsheet of publishers and contests and their deadlines.

Have and use a Submittable account.

Remember: the only thing you can control is what’s on the page, but practicing these things will help your professional life as a poet.

Where to begin?

Item #46: You should begin by making a poetry map of everyone you know in poetry and their connections. Making a map of who you know in poetry is a good starting place for professional development because it allows you to visualize the relationships you already have. My position is that practicing poetry is not an individual endeavor, based on people turning themselves into brands, but a communal activity in which we all can rely on each other.

My map shows relationships that flow in multiple directions. It shows the interconnectedness of poetry: poems are written in solitude, but are intended for the society of other readers. Being available to help others is vital to keeping poetry healthy.

For further reading:

Bly, Carol. Beyond the Writers’ Workshop: New Ways to Write Creative Nonfiction. New York: Anchor Books, 2001 [Buy at Bookshop]

Kunitz, Stanley. Interviews and Encounters with Stanley Kunitz. New York: Sheep Meadow Press, 1993. [Buy at Bookshop]

Lorde, Audre. A Burst of Light: and other essays. Ixia Press, 2017. [Buy at Bookshop]

The musician and public intellectual Tanya Kalmanovitch writes about her artistic practice in her newsletter, The Rest. I am continuously impressed by these newsletters: she tries to get artists to do better, and gives readers specific skills to develop. Tanya teaches a course on Entrepreneurship and Social Action at the New School with her colleague John-Morgan Bush. He generated a list of 50 self-assessment criteria for musicians’ professional development skills. Tanya shared the list with me, which I’ve modified here for poets.

About Sean Singer

My mind is blown by how helpful this is. Definitely saving to look back at regularly for future reference.

Wonderful list! Thanks for taking the time to create and share it.