Writing Problems: Sincerity

Niedecker, Zukofsky, Kunitz, Stafford, Keats

Poems are the wound and the salve. Poems are the green hillocks covering a stone pyramid. Poems are flaming swords that guard the Tree of Life. Poems let us become different shapes, substances, and minds. Poems are the scales of creatures that yield pure dreams, they have the same colors as the foliage, and they lurk and feed. Poems are perilous incisions; they dispel deceptions. From the mist of the deep self, all darknesses converge: webfooted, neckless, without mouths, a machine twisting pistons in the air. But how do we know, when we pick up a poem, that’s it’s being trustworthy? Is the poem’s gesture sincere or insincere?

Sincerity in poetry means a freedom from falsification, a kind of genuineness, and no dissimulation. Part of the pleasure of the voice in a poem is its authenticity, an insistence that it is a real voice, not a subterfuge, but someone’s human voice speaking to the reader of the poem.

Even though the voice in a poem is a fiction, and a kind of imagined autobiographical statement, it is nonetheless a reflection of something raw and real. Sincerity synthesizes feeling and action because the voice has pushed out of the self in a “real” way for the reader. Sincerity is an axial concept: it’s the way a speaker in a poem interprets their relationship to society.

Exigencies of modern life

By putting out honest feelings, the poet is being sincere toward a reader. Sincerity thought of in this way can be traced to the Objectivists— the primaries were Louis Zukofsky, Lorine Niedecker, Charles Reznikoff, Basil Bunting, and George Oppen—who challenged Imagism on the grounds that it had a kind of gentility that was foreign to the exigencies of modern life.

From February 1957 through November 1963 Niedecker worked as cleaning the Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, Memorial Hospital. She told Zukofsky: “I should draw a picture of myself covered with dust mops, pails, kitchen cleanser, brooms, etc. wondering where I am down those long halls past all those doors.”

Oppen was the sole survivor of a company of three soldiers pinned in a foxhole in Alsace by direct gunfire during the Battle of the Bulge. These extremities, Zukofsky said in 1932, made the Objectivists insist that “the image [was] as a test of sincerity against...a picture intended for the delectation of the reader who may be imagined to admire the quaintness and ingenuity of the poet, but can scarcely have been part of the poet’s attempt to find himself in the world….”

Where it lies hidden

As the world becomes increasingly precarious and the possibility of world-ending climate disaster more and more probable, poets have to be merciless and savage in their movement of the self into language. Stanley Kunitz says that sincerity in a poem is one that finds where it is hidden:

“Finding where it lies hidden” means digging. It means being connected to one’s intention, so that the spirit level of the poem in the head most closely resembles what is on the page.

William Stafford elaborates that a poems is also more than this intention:

It’s possible that the missing element is this issue of sincerity. Treating oneself in a poem fully and sincerely means bringing-into-existence the truthful attempt to uncover or recover something deep inside.

Restorative justice

An article recently published in Frontiers in Psychology showed the importance of sincerity in restorative justice. Researchers used eye tracking to understand how victims perceive and interpret an offender’s apology in a simulation. The study was able to quantify “that receiving an apology from the offender can positively affect the victim’s feelings of strength such as power, influence, and self-esteem, subsumed under the agency need dimension of the victim.” The study also showed how “The victims’ inferences of suffering, responsibility taking, and degree of empathy for the victim in the offender’s apology jointly positively predict the perceived sincerity of the apology.”

Similarly, the reader can sense the ways in which the poem expresses responsibility for taking the suffering or joy or empathy in the voice seriously. It is an openness and willingness to be clear, to be forthright, to know the person in the poem has done their best to be their language.

If the water were clear enough

When poems are unsuccessful it is often because of an abrasion of the reader feeling as though the poem is lacking integrity. When poems are successful, there is the opposite feeling: surety that the poem has gone as deeply as possible to find the real.

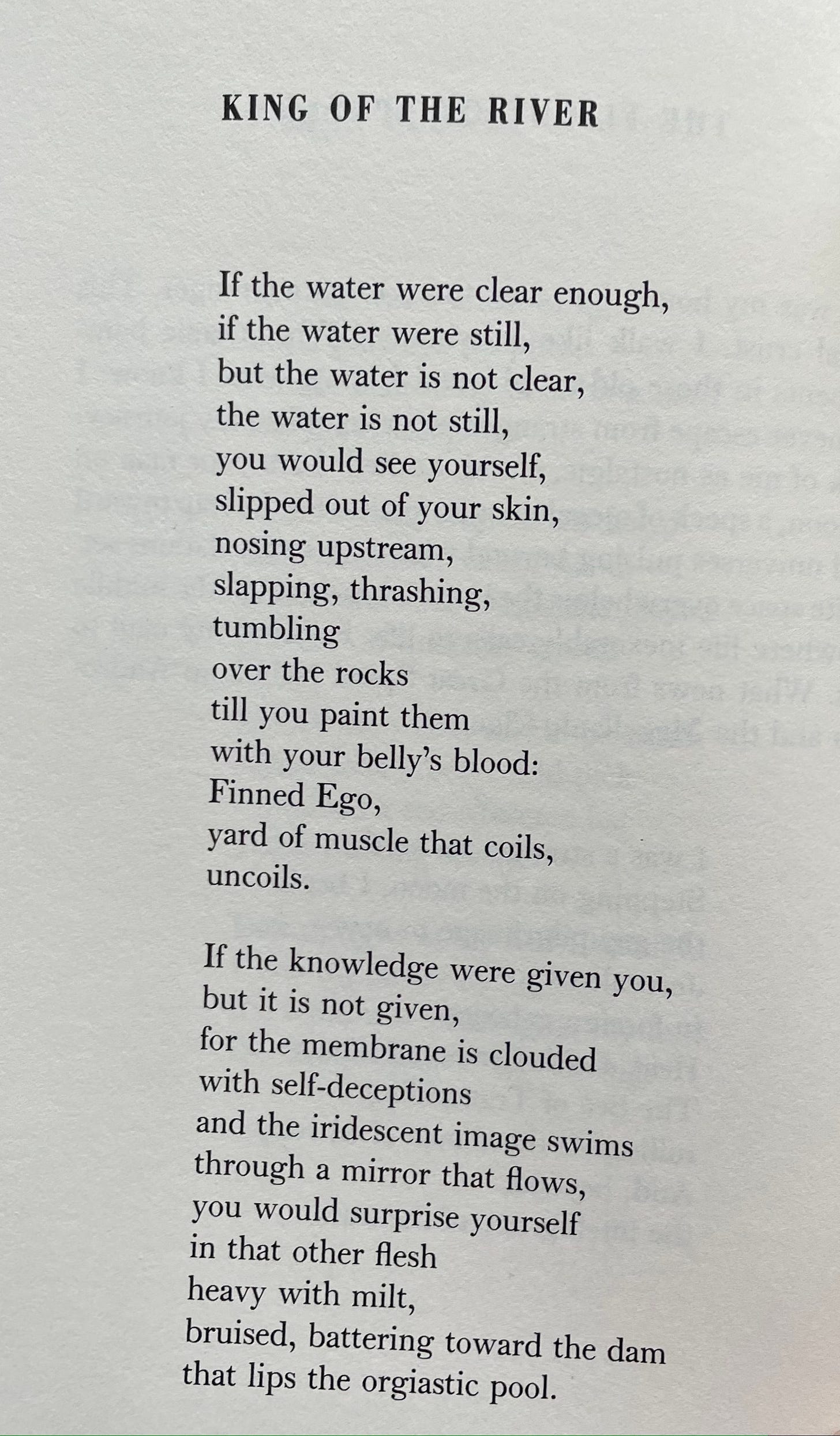

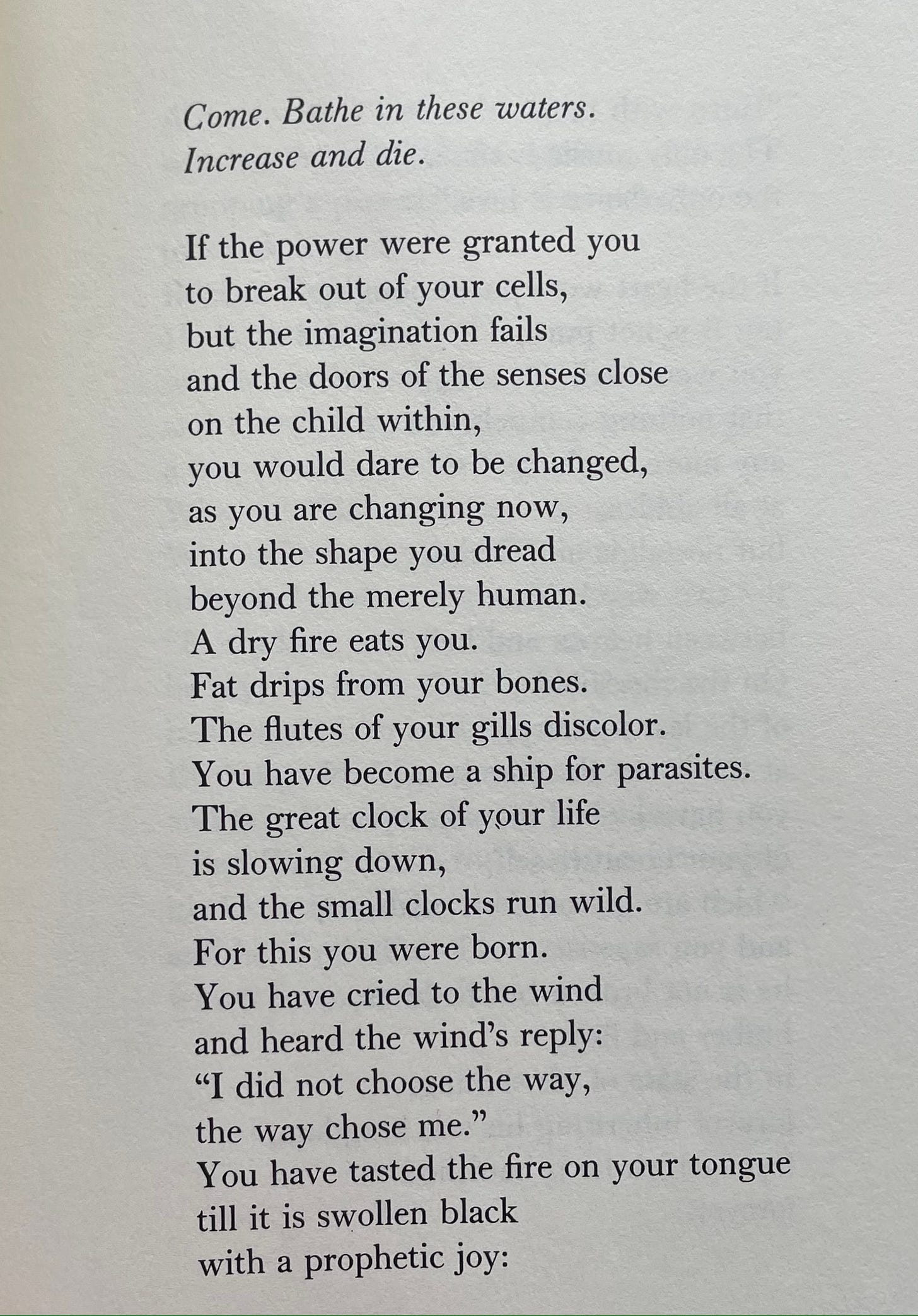

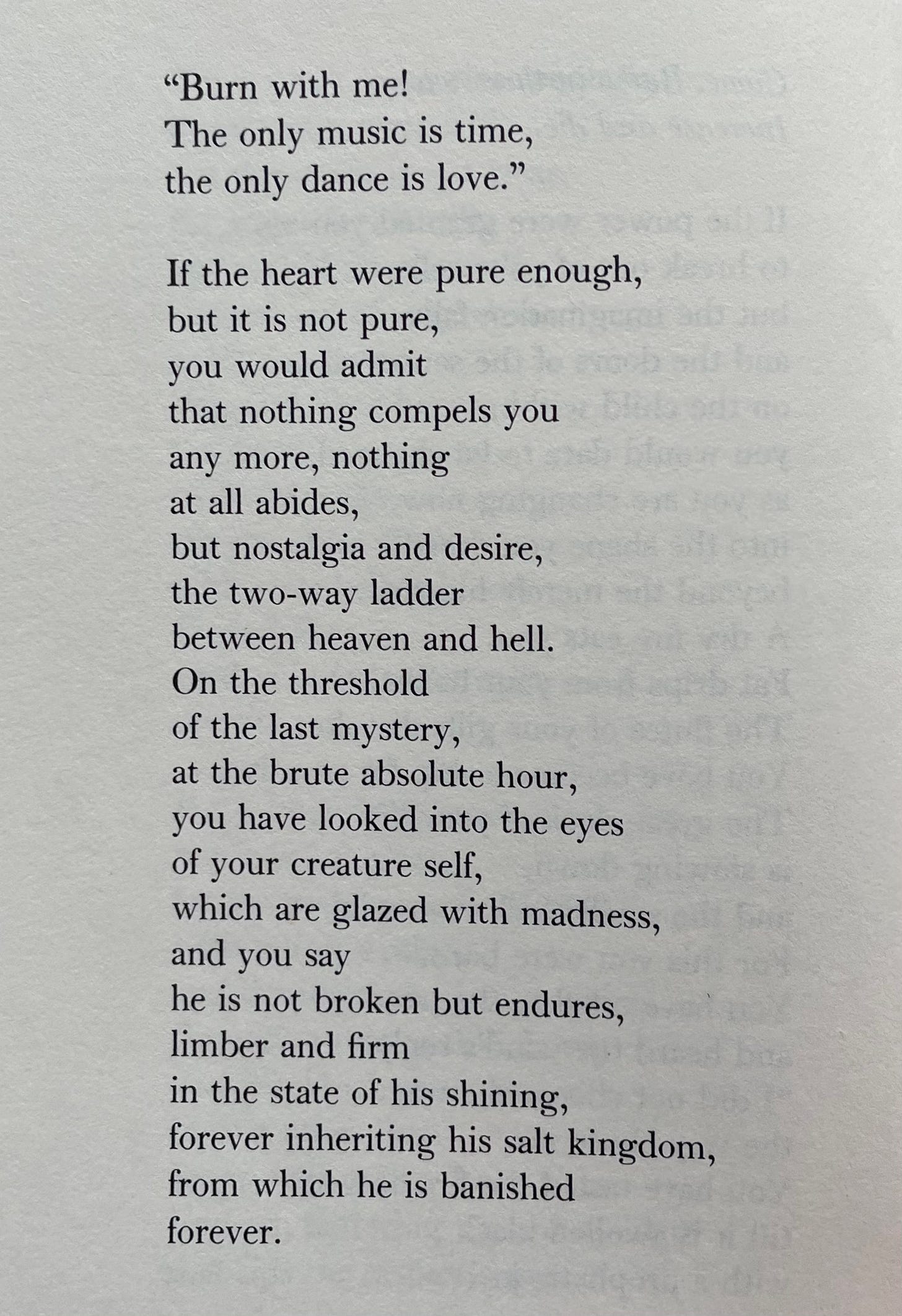

Stanley Kunitz’s poem “King of the River” is one such poem:

The poem takes the self-destructive lifecycle of a salmon as a metaphor for the poet’s position of dealing in contraries. The poem moves from dark to light, from profane to sacred. Reading it I am always confident in the voice’s sincerity; I don’t for a moment doubt Kunitz dug as deeply as possible to connect with me; to make living and dying important again.

“The eternal Being, the Principle of Beauty, and the Memory”

Poetry dreams of perfection. If it didn’t it would not be as life-enhancing as it is. When Keats wrote about his humility toward “the eternal Being, the Principle of Beauty, and the Memory of great Men,” he was talking about the poet’s ability to bridge solitude and communion, the Self into the Many.

Poetry is constantly at odds with our society. Like killing snakes, poetry exerts a constant pressuring: it pushes against all the institutions that want to make everything look and become alike.

America has an endless supply of parasitic ideas and products, sometimes ironically called “goods.” This means America is also anemic when it comes to the places poems penetrate: the film between the inexpressible and the real.

If poetry is to give any expression to what being a person is like it will also have to take the climate emergency seriously. There are horrors that will be inevitable by 2050, and are unimaginable now. If poems are to think this through, then they need sincerity.

A rise in temperature of only two degrees will create genocide among island nations, and cities in Asia and the Middle East will become too hot to be habitable. There could be as many as 100 million climate refugees. Some places will have multiple natural disasters simultaneously. In addition, as the ice at the top of the Earth melts, its reflective white surface will no longer reflect heat back into space, and this in and of itself can raise the temperature of the Earth by two degrees.

From the fumes poetry has to do better and more. Sincerity has to consider all this, from the anthilll to cloud formations. It can’t be left to the service of the ego, or self-expression.

Sincerity also demands a retreat from sentimentality, a grounding in seriousness and conscience. Part of people’s turning away from their collective responsibility to the Earth and to each other is precisely because they don’t pause, slow down, and think through what is happening. Poetry brings the loveless into its fold, like fruit to the Dead Sea, and recognizes people are nothing without language to bring-into-existence-as-creativity.

For further reading:

Kunitz, Stanley. Interviews and Encounters with Stanley Kunitz. New York: Sheep Meadow, 1993. [Buy at Bookshop]

—. Passing Through: The Later Poems, New and Selected. New York: Norton, 1997. [Buy at Bookshop]

Stafford, William. Crossing Unmarked Snow: Further Views on the Writer's Vocation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer