Writing Problems: "The card says 'Moops!'"

Rich, Gilbert, Merwin, Melnick, Ravitch

On the October 7, 1992 episode of Seinfeld, George and Susan play Trivial Pursuit with the “Bubble Boy.” George reads the question: “Who invaded Spain in the 8th century?” Bubble Boy gives the correct answer, “the Moors,” but due to a misprint, the question card says the answer is “the Moops.” George, irritated by Donald’s condescension, refuses to back-down. “The card says ‘Moops!’” George insists and won’t concede, until Susan accidentally depressurizes the bubble, crushing Bubble Boy.

What do the Moops have to do with poetry? I often encounter people who insist on reading poems literally. They are resistant to creating a poem’s meaning halfway, or they feel the poet has a fixed meaning to a poem, or they feel a poem is a puzzle that needs to be decoded, or that they need an MFA to be qualified to read a poem, or they feel the style and aesthetics of a poem violate their own style and aesthetics, and are resistant to the poem even existing.

It may seem obvious, but it bears repeating, that poems are crafted things. The poet only has a partial role in forming a poem’s meaning. In fact, the most malleable, porous, and lasting poems tend to elude fixed meanings; they instead provide clarity to mystery.

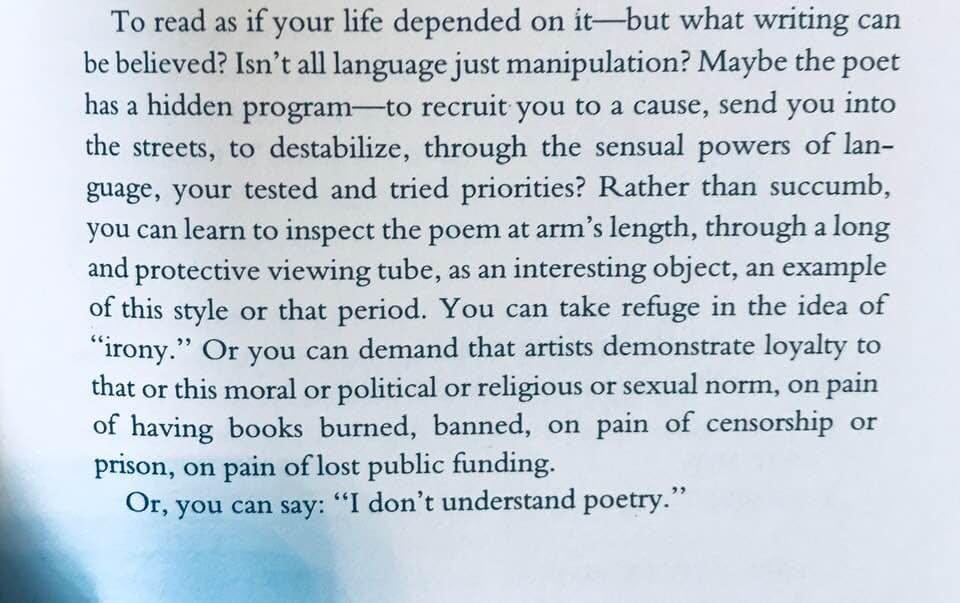

Adrienne Rich, in What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics, made the following observation:

We happen to live at moment that is going to get worse before it gets better. The world went inside the internet and became the world. There are at least 75 million adults in the United States who live in a Bizarro world of “alternative facts,” who feel comforted by conspiracy theories, who, when confronted by information that contradicts their worldview, prefer to dismiss that information and the people who provided the information.

So, a poem may not conform to your worldview, your tastes, or what you think a poem can be. I often hear students get exasperated if a poem stretches the bounds of what they think poetry includes.

Jack Gilbert had an insight on this topic:

There isn’t any one correct way to write poetry. Poetry is a word like love: an endless confusion of different things all warped into one word because no vocabulary of discrimination exists.

Some people would like a poem to be comforting, like a warm fuzzy or a meme, a thing that brings them to a place of equilibrium, like McDonald’s, of sugar, salt, and fat. There are poets who’ve made a career out of this kind of poem. For others, poems balance critique and celebration, they are made to make a reader imbalanced, ambiguous, pushed into mystery, and left in wonderment.

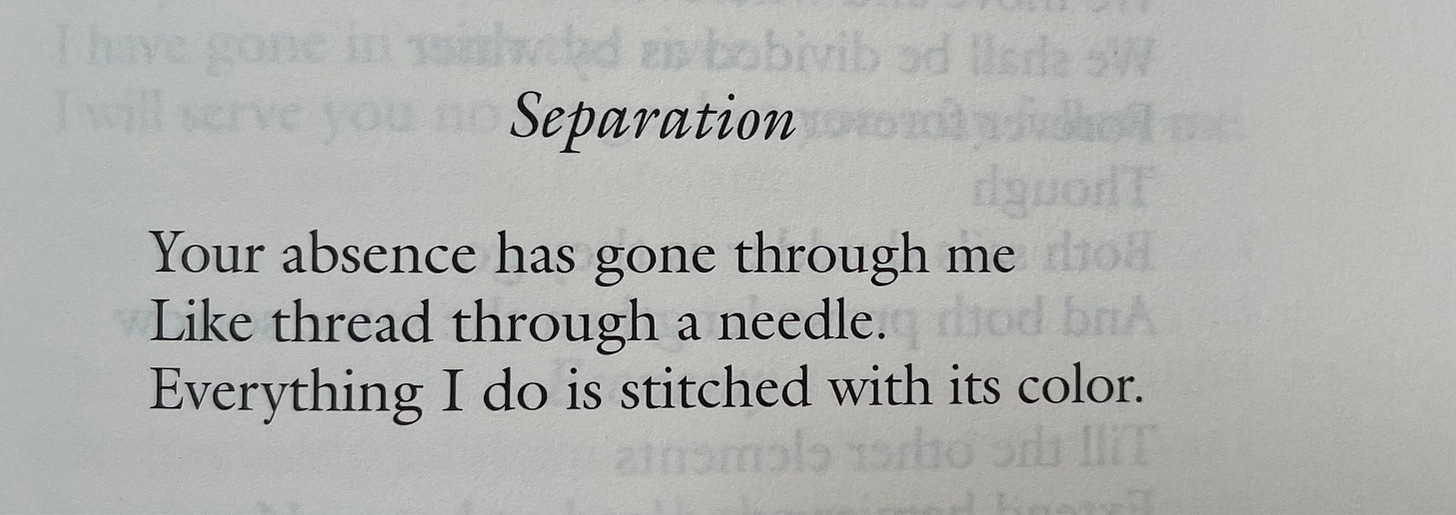

Part of understanding poetry is technical knowledge (caesuras, iambs, syllables, forms) and part of it is psychodynamic (what do we know about the text or context). Reading some poems elicits a direct or straightforward response, as in Merwin’s “Separation:”

Others may be so unique in their expression that you have to just accept them and experience them for what they are, as in this poem by David Melnick:

A poem like this is not easily going to reveal its secrets. You may say: “Well, I don’t have time or patience for this! I’m not Helen Vendler!” Everyone is entitled to their opinion, but people who are informed have more of a right. Imagine the potential and power a person could have if they could feel they could interpret any text, no matter how opaque.

There are so many approaches to what a poem could be, probably as many as there are poets. Imagine types of poems and your attraction or repulsion to them, and why:

Ideas / Philosophical, where the energy of the poem comes from a thought

“I know breakthrough as I tell / the dream surpassed. The Art of the Fugue resembles / water-springs in the Negev.”—Geoffrey Hill, section VI, The Orchards of Syon

Glandular / Liver, where the energy of the poem secrets from your skin, and you go back to your origins, the beginning stirrings of self

“Now, my friends emerge / Beneath the wide wide Heaven—and view again / The many-steepled tract magnificent / Of hilly fields and meadows, and the sea, / With some fair bark, perhaps, whose sails light up / The slip of smooth clear blue betwixt two Isles / Of purple shadow!”—Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison”

Embodied / Felt, where the energy of the poem comes from the poet’s own physicality

“Whenever I catch two men kiss, in the streets, or in the movies, / I’m filled with so much envy, always wanting to be filled up / the way a woman would. Their jaws interlock as if to kill—”—Tory Dent, “Family Romance,” HIV, Mon Amour

Ha-Ha / Joke, where the energy of the poem has a setup, story, and punchline; all timing and stretching of expectation

“‘Oh, honey, are you okay?’ / I asked the woman in the bathroom, / soaking wet as if she’d just emerged / from the shower.”—Jennifer L. Knox, “Wolverine Season,” Crushing It

Portrait / Jewel, where the energy of the poem is in a very small container, controlled fully like an isotope

“Reaching late his flower, / Round her chamber hums- / Counts his nectars- / Enters - and is lost in Balms.”—Emily Dickinson

River / Horizontal Energy, where the energy of the poem moves across and then down the page forcefully

“At night, in the fish-light of the moon, the dead wear our white shirts / To stay warm, and litter the fields.”—Charles Wright, “Homage to Paul Cézanne,” The Southern Cross

Question / Bully, where the energy of the poem insists the reader reveal their own feelings even if the poet doesn’t do the same

“Does anyone / not see it? Driving by a field / of spray-painted sheep, I think / the world is not all changed.”—Maggie Smith, “Poem Beginning with a Line from It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown”

Back foot / Imbalance, where the energy of the poem comes from discomfort or unevenness

“He was first seen in a Louisiana bayou, / Playing chess with an intellectual lobster.”—Bob Kaufman, “Grandfather Was Queer, Too,” Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness

Of course these overlap and condense, combine and can appear together, and there are other types of sparks in poems with lots of precedent.

When encountering a poem, you can’t just insist that it be toilet-trained, comfortable, fair, absolute, rosy, or polite. No poet means a specific thing because language is not an order at a coffeeshop. It’s not a one-to-one relation.

So, back to the Moops. You can’t relate to a poem literally, or approach a poem without riskiness. You can’t seriously think, like George insists, that the Moops invaded Spain in the 8th century. (George was trying to get the Bubble Boy’s goat). You have to bring your knowledge, life experience, doubts, wishes, and possibilities with you into the poem.

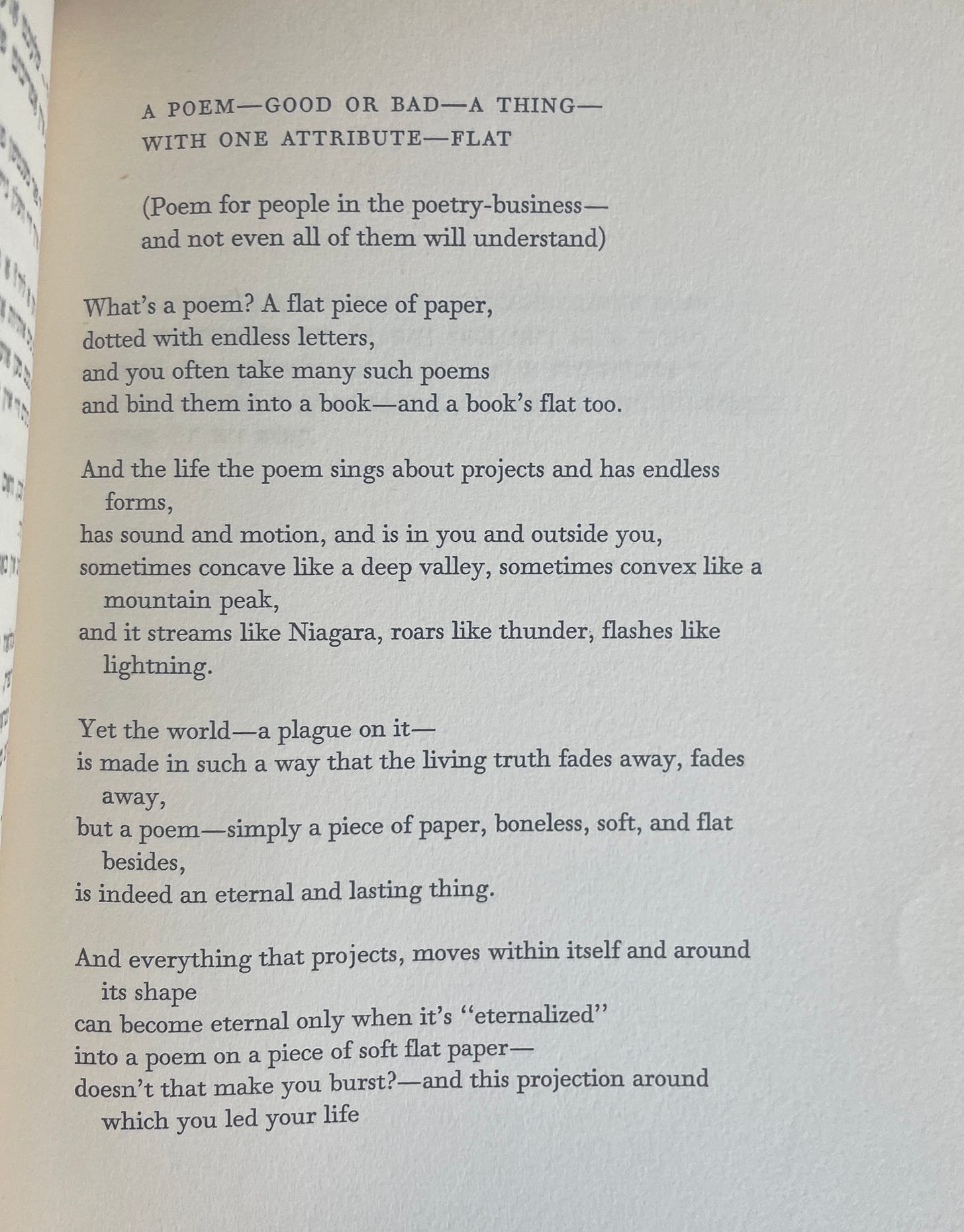

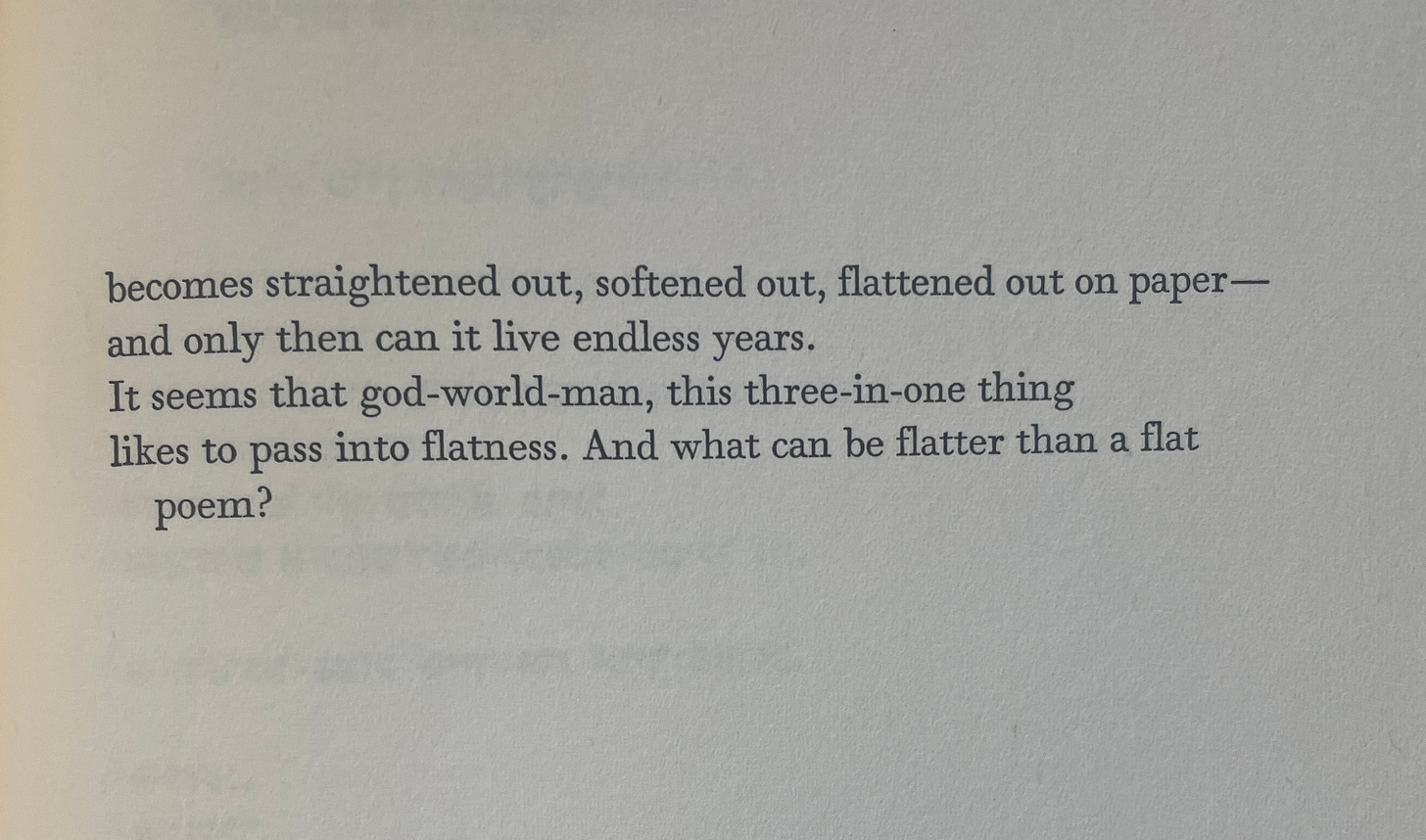

To finish, I offer a poem, “A Poem—Good or Bad—A Thing—With One Attribute—Flat (Poem for people in the poetry-business—and not even all of them will understand)” written in Yiddish by the Canadian poet Melech Ravitch (1893-1976) and translated by Ruth Whitman that perhaps has no fixed meaning, but instead, goes into the dark depths of what a poem is, a place where the sperm whales hunt for giant squid.

Poems are flat, but it’s our job as poets to lick them into shape, like a mother bear licks her cub into shape. A poem’s meaning is not fixed, but emergent and dynamic; not external or transcendental, but intrinsic and immanent, coexisting with matter in which it develops towards its fullest realization.

Even if the card says “Moops!” the poem is still flat until its meaning is soaked through with the reader giving of themselves as if the poem was an embrace or a handshake.

For further reading:

Melnick, David. A Pin's Fee. Philadelphia: Hiding Press, 2019. [Buy from Hiding Press]

Merwin, William Stanley. The second four books of poems. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 1993. [Buy at Bookshop]

Rich, Adrienne. What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics. New York: W.W. Norton, 2003. [Buy at Bookshop]

Whitman Ruth, ed. An Anthology of Modern Yiddish Poetry. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1966. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

This is the one I've been waiting for.

Love love love