Craft: Jennifer Martelli

Jennifer Martelli (1963-2025), who died September 25, was a special and important poet. Her poems were made from the mortar of her home towns in Massachusetts (Revere, Marblehead, and Salem), infusing intense character studies and astute political observations with Italian-American feminism that was by turns cheeky or set-jawed severe.

These studies included Kitty Genovese, who was stabbed to death in Queens in 1964 in front of 38 witnesses, none of whom came to her aid; and Geraldine Ferraro, who was, in 1984, the first woman on a national political ticket. Martelli showed how the responses in the cultural imagination to these historical moments and human beings are not only the stories of Italian-American women with whom she identified: they are the story of how America got where it is today.

Though politically and psychologically minded, her spirit conveyed a calm assurance and gentleness. She was enraged by the political landscape, particularly its retrograde policies and attitudes towards women. But, she did not let it spoil her general affection for the universe,wearing her wit and imagination as a kind of asbestos suit against the exposure suffered by women who write directly into toxicity.

Indeed, she seemed at ease with living among overlapping contradictions—afflicted with cancer, but grateful for her blessings; creating vivid poems under a government that sought to destroy what she wrote and cared about; using her self-deprecating humor and graceful energy to support and uplift every other writer she encountered even when she was, most often, making poems better than anyone.

The Queen of Queens memorializes the 1980s, but it does more than that. It’s political without being histrionic; it’s clever without being superior; and it’s impressionistic without relying on a personal set of inscrutable symbols. It also frames what it’s like to live in the United States in 2025 through the events of the same country in the 1980s. The book uses overlapping metaphors, particularly pearls, to understand the potential and meaning of Geraldine Ferraro’s political career. History makes smoke and shadows on the current moment, thus it’s frequently illegible to people; easier to see if someone like Martelli can make solid shapes from those phantoms.

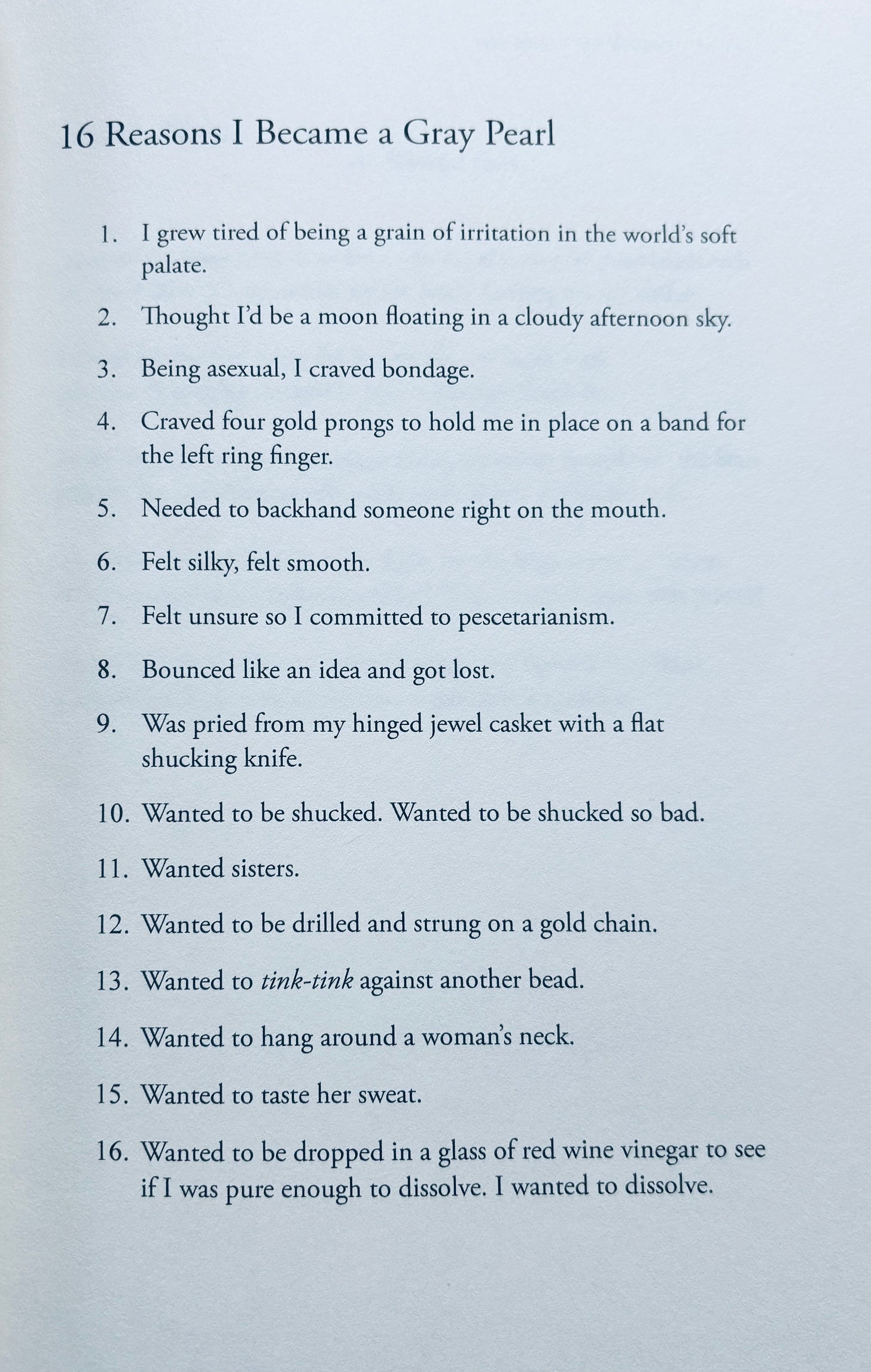

“16 Reasons I Became a Gray Pearl” is a list poem that introduces many of the threads and themes in Queen of Queens. It allows a porousness from a precious object to become a path to self-inquiry, a cipher to interpret the history that comes later, and a method to explore an organic substance that seems otherworldly on its surface.

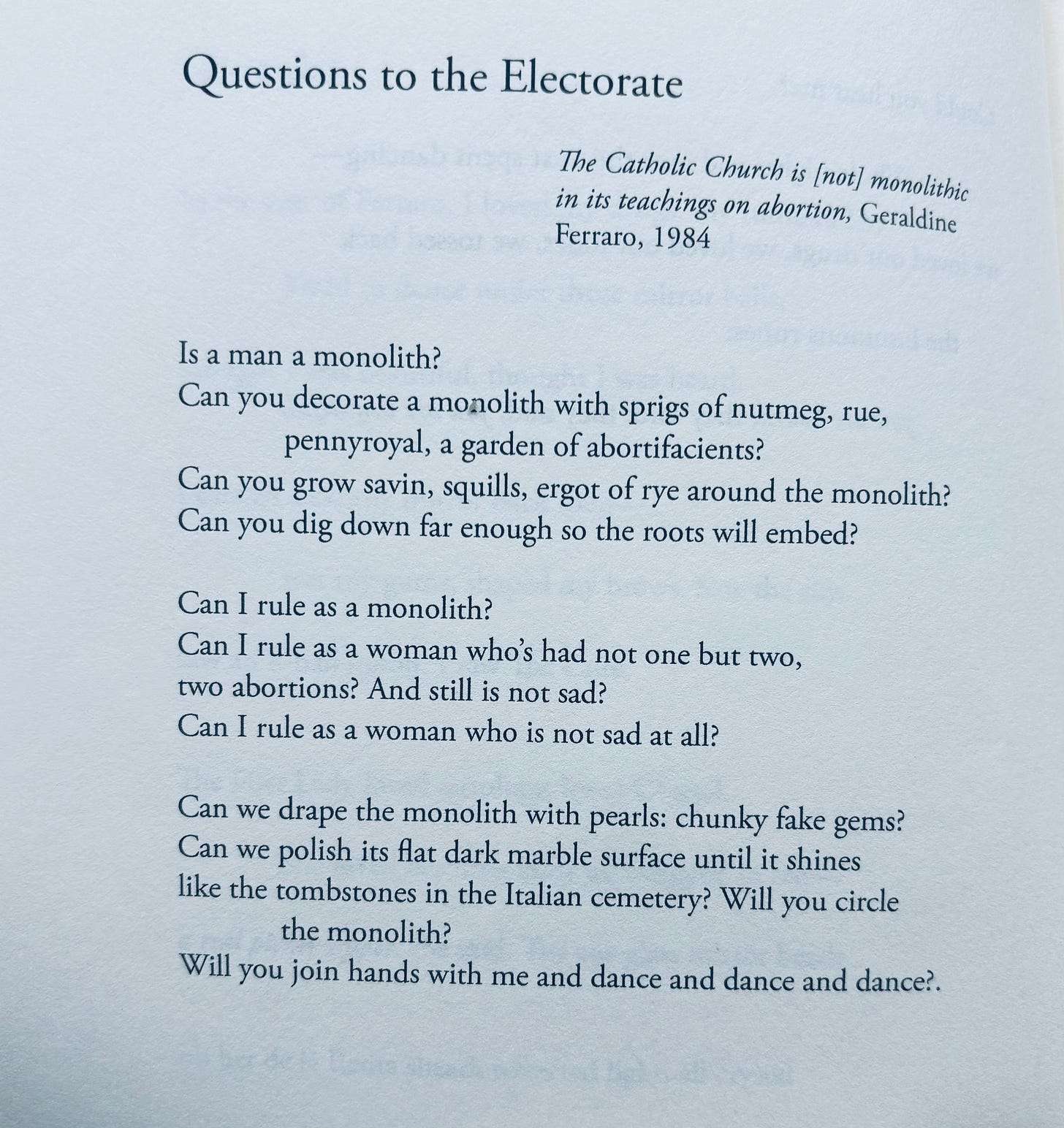

“Questions to the Electorate” uses 12 quatrains to become open-ended and expansive. Again the pearls appear as crystal balls that look forward and look back. The poem also evokes ancient, organic items that become a kind of spell. As the questions build, so the pronouns change from second to first singular to first plural. The reader, thus, is invited to ask their own set of questions.

Martelli was unafraid to allow poetry’s multilayered-ness to help her read history as poetry and the other way around. In her poems past, present and future seethe below the surface. Her poems tend to glisten with the way she made her own life into legend: she was among the women she described and evoked, and her poems closely re-periodize cultural responses to feminism.

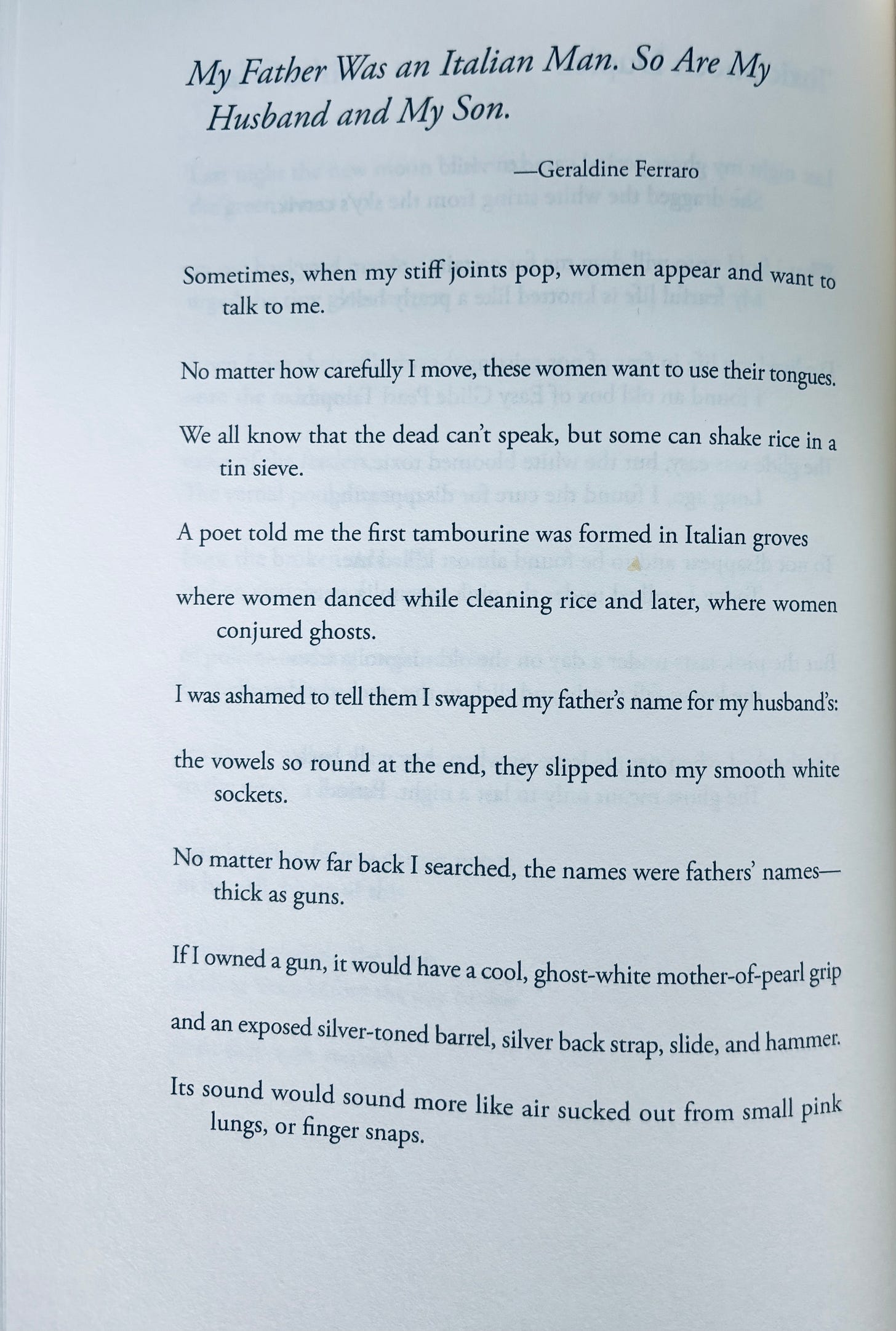

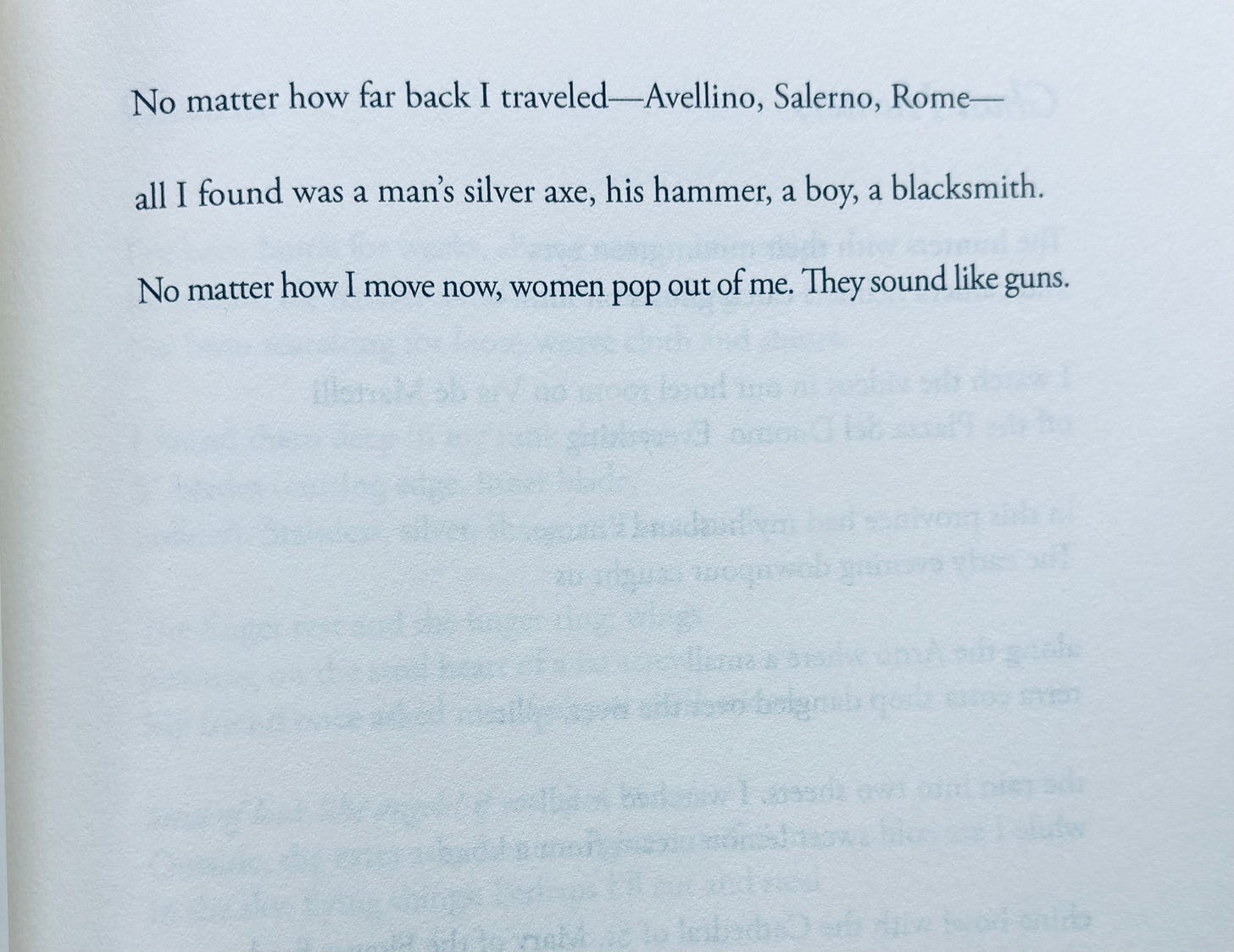

“My Father Was an Italian Man. So Are My Husband and My Son” is a persona poem, even though much of its scaffolding for the persona is an act of self-portraiture. (“Martelli” literally means “hammer.”) Here, the pearl becomes the grip of a pistol. Long, single lines imply a steadiness combined with a sense of overflowing. True to Martelli’s speciality, the past becomes a path to understand the speaker in her attempts to read the present.

The pearls in this poem become a kind of talisman to allow Ferraro travel as the first woman and first Italian-American person to run for Vice President. Ferraro becomes totemic for the speaker, a symbol of possibility.

Martelli’s poems have an undercurrent of discontentment and danger. Her female speakers have an adversary in the dominant culture, but not as a way toward sentimentality, bitterness, or self-aggrandizement. Rather, the poems bring resistance against apathy and mediocrity.

My Tarantella is similar in scope to The Queen of Queens, but the violence and tragedy of its particulars feel closer to the surface. The poems arise from a psychological position of anger and negativity, whereas in The Queen of Queens that anger is often subsumed by possibility and revelation.

In all her books Martelli fights for this revelation. To that end, each of Martelli’s poems is an act of participation: not merely a moment of consumption, but of making meaning. Her poems do something else important: they show that history is a comment on the present, and that poetry is a powerful tool to study and interpret historical events.

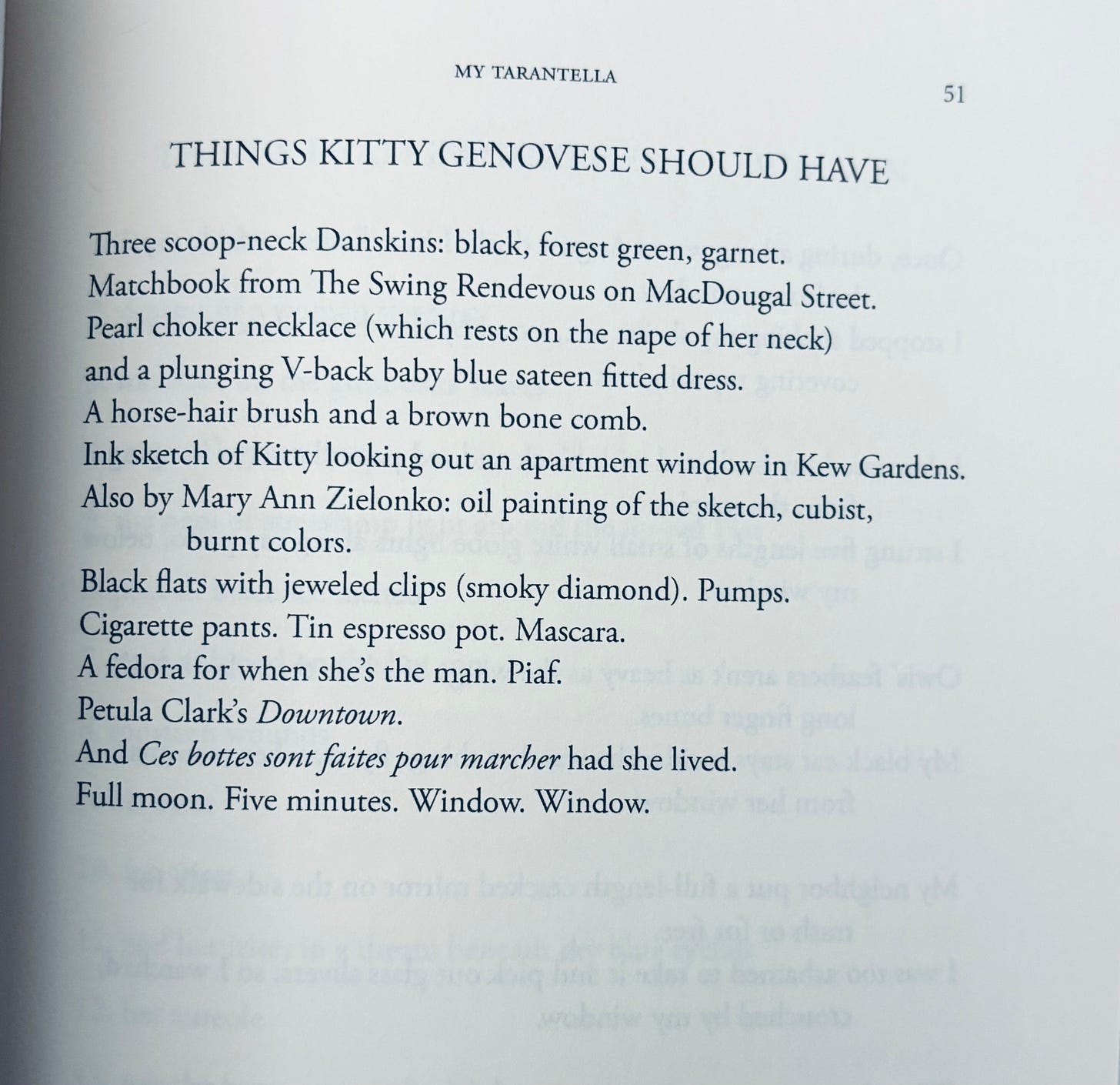

My Tarantella also begins with a numbered list poem, but this one has seven items. Kitty Genovese was not a celebrity or a known person. Indeed, her horrible end is the only reason we know her name. But she has become not only a staple of psychology textbooks as an example of “bystander syndrome.” Her murder was a harbinger of Vietnam, Watergate, the apathy and vile disengagement from clear and present acts that now seems commonplace in America.

Martelli uses poetry to be a voice of the other for the other. In “Kitty Genovese, Being Dead, Conflates,” a series of vulnerable couplets allow the multiple meanings of “bats” to spark and fly. Witnesses to the stabbing had all kinds of reasons for not intervening: “We thought it was a lovers’ quarrel.”; “Frankly, we were afraid.”; “I was tired.”

Bats are wooden instruments used to hit baseballs, hitting something or someone, the nocturnal flying mammal, as well as a derogatory word for a woman. Martelli relies on the potency of her images and never explains herself. This poem, for instance, pushes against the diffusion of responsibility in the Genovese case and allows her a voice (real or imagined) to keep alive the idea of women’s possibilities.

Martelli uses images in “Things Kitty Genovese Should Have” perhaps from her own lived experience to summon a specific, yet ordinary person. She ignites both questions of aesthetic taste and moral taste. Aesthetic taste is the usual kind: “I like navy blue,” “I prefer Billie Holiday’s early recordings,” or “I like black coffee.” Moral taste is something else: an interest in justice, not giving accommodation to evil, having bravery to write even though our culture models brutality.

Brutality has and is always part of the American landscape, and there is perhaps no word that shows ignorance of this fact than “unprecedented.” It’s all precedented. Martelli’s poems show her reaching back into herself—often in unexpected ways even to herself—into finding witness; this observation of herself flowing through time means she can face another day.

She doesn’t only name the terrors coming from the outside, but those from within which are usually more palpable, muscular, and provisional. Her home of Salem, for example, was the site of something unimaginable.

Psychic Party Under the Bottle Tree doesn’t explicitly get into the Salem Witch Trials, where, in the 1690s, more than 200 people were accused of witchcraft, 30 people were found guilty, and 19 of whom were executed by hanging (14 of those were women). However, Psychic Party Under the Bottle Tree is never far from the shame and violence that permeates what purports to be an educated and moral American society.

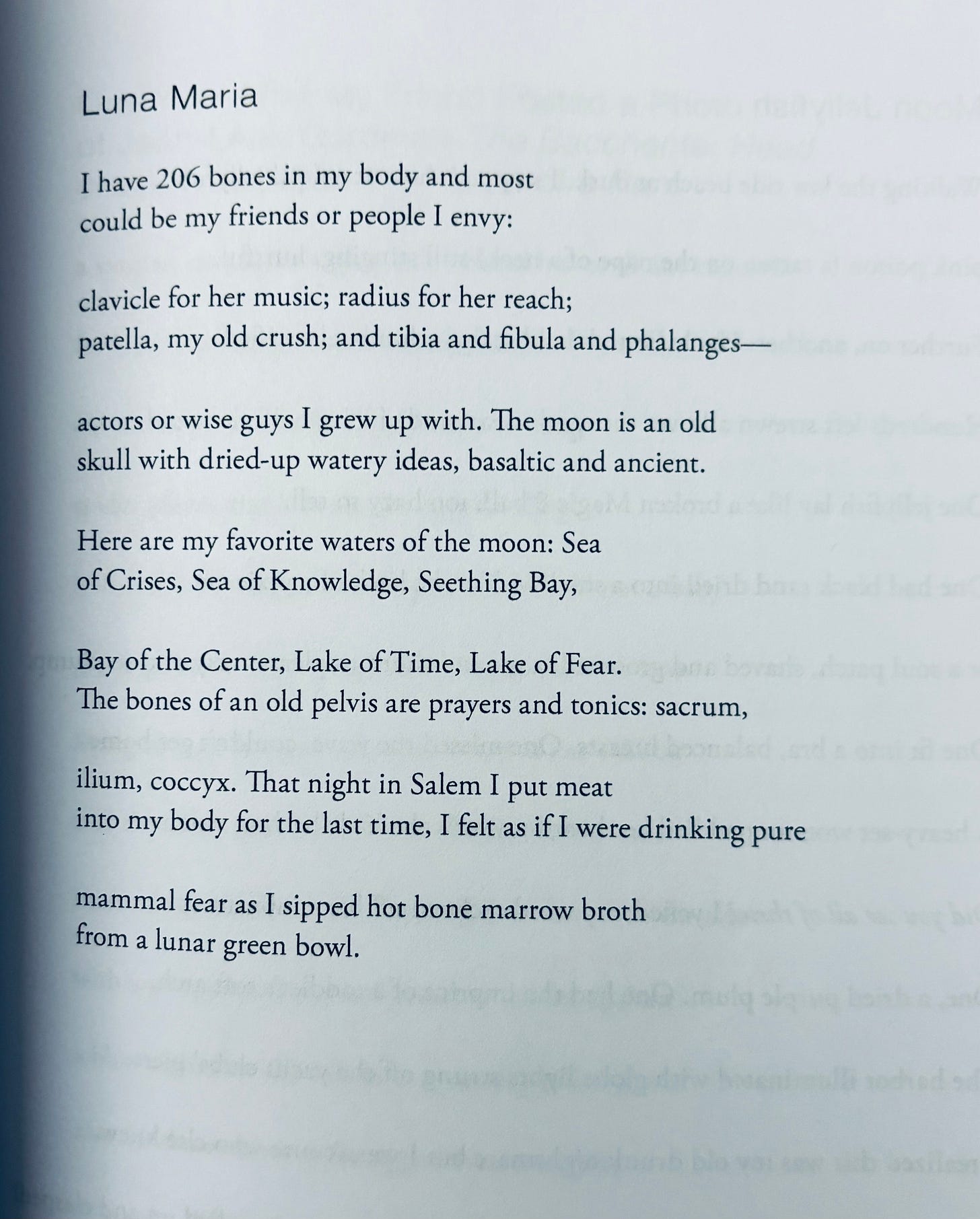

Martelli’s quick changing invention is everywhere in the book. Anyone would give eyeteeth for her facility with images and their movement from one turn to the next and the next.

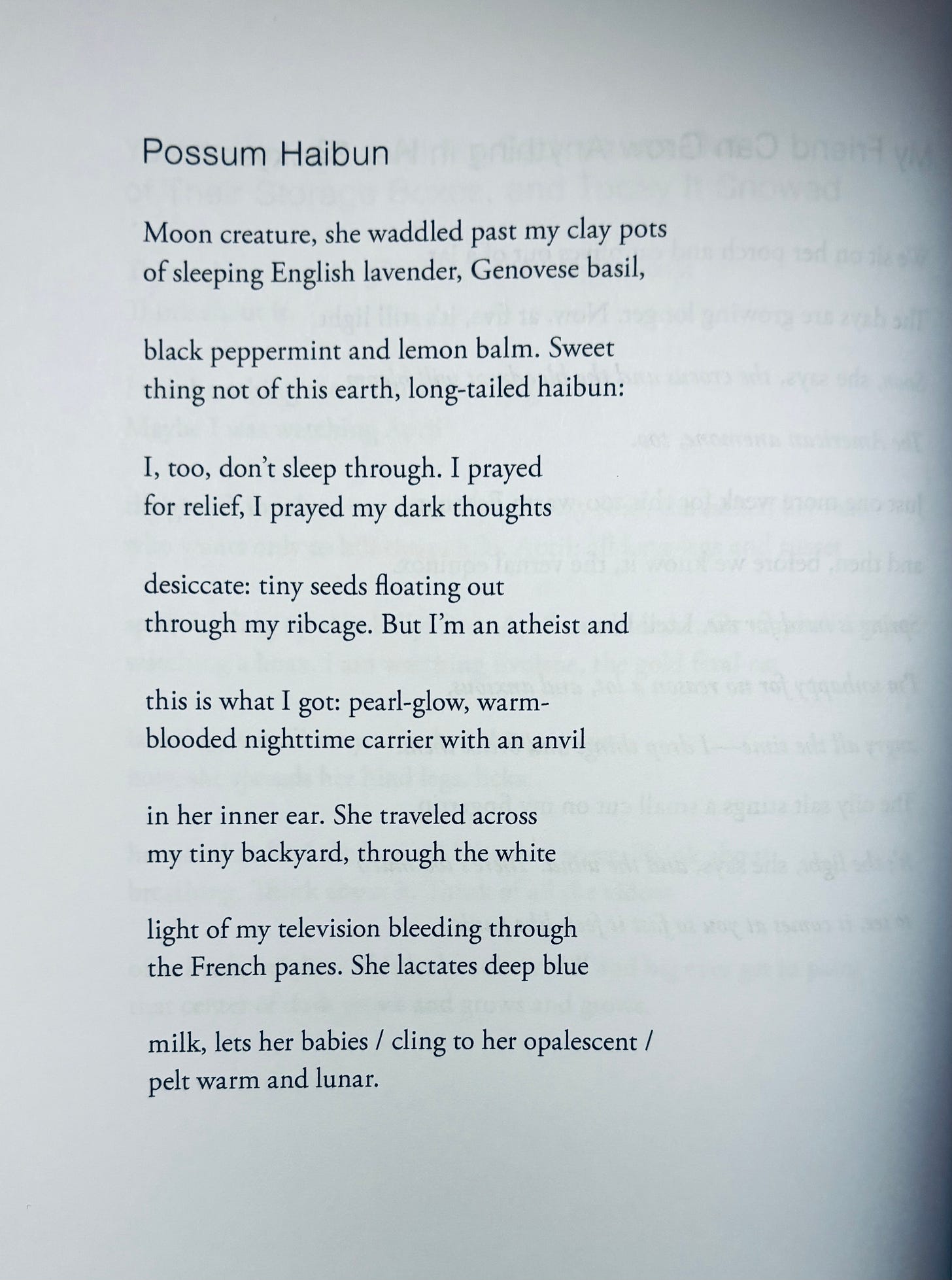

In “Possum Haibun” the speaker finds identification and curiosity with the creature. Interiority becomes wild again, and the inside of the room becomes undomesticated.

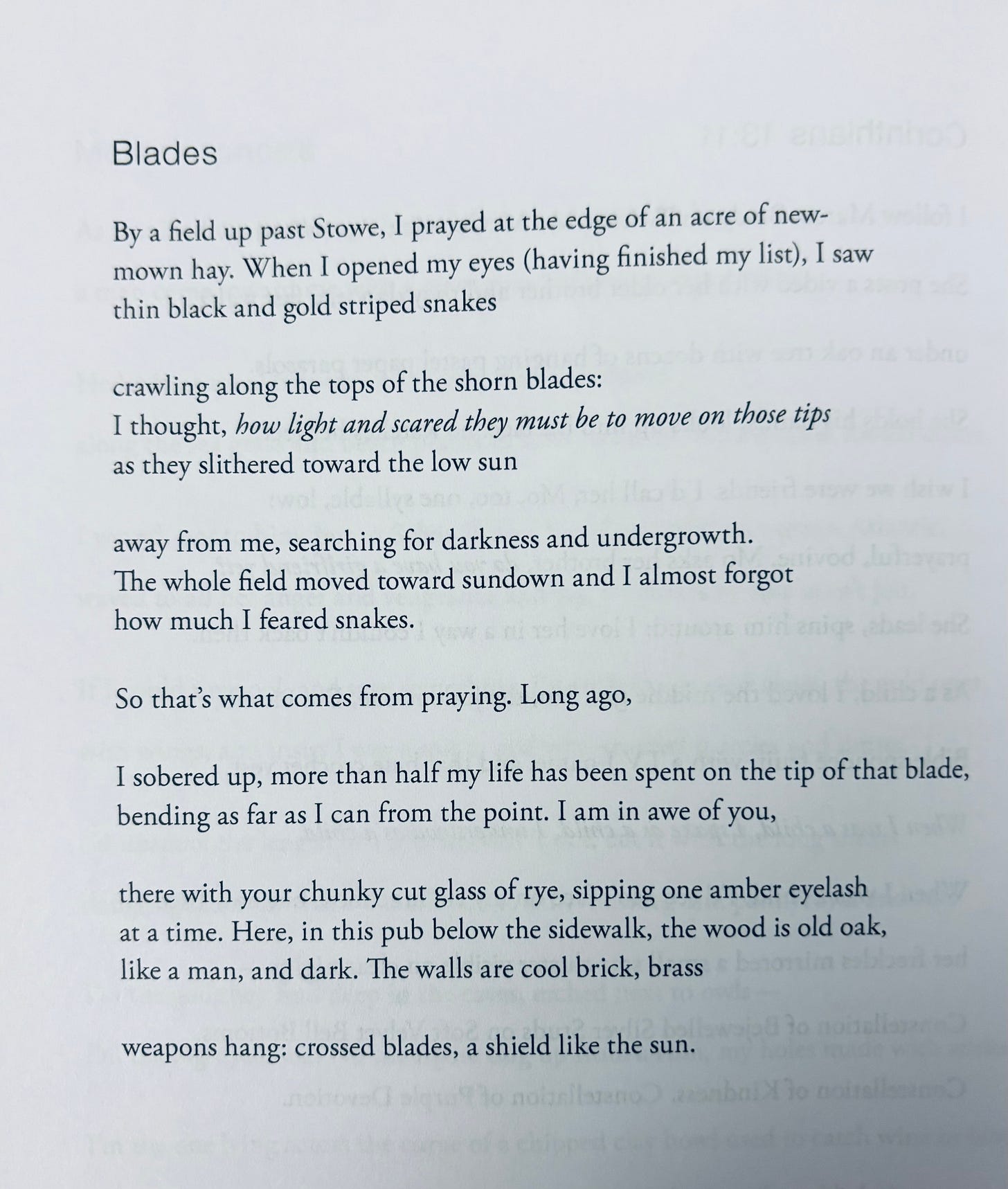

“Blades” is the last poem in her last published book. It is a reminder that there are poets around, like Martelli, who don’t get another ten years or ten books. We have to throw all of the weapons and predators into the poems now, and force the readers to look directly into the sun.

It’s the responsibility of me, and others in her network, to preserve and spread her readership. It should have been bigger, and it still can be. And it is when a poet is newly gone that there is the most hope for her legacy, as those who knew her can deliver her work to new audiences with authentic affection and commitment.

Poetry relationships flow in multiple directions. These show interconnectedness of poetry: poems are written in solitude, but are intended for the society of other readers. Being available to help others is vital to keeping poetry healthy.

My wish is for people to understand Martelli’s poetry as a way to understand poetry broadly. When the floor itself is unstable, and the walls around us seem shaky—either because of political threats, physical threats, or the difficulty of finding poetry among it all—Martelli showed how dexterity with language and decency in spirit can be a guidepost.

Her grace is right there, in all the poems, and as such, she herself is right there as well.

For further reading:

Martelli, Jennifer. Psychic Party Under the Bottle Tree. Boston: Lily Poetry Review Books, 2024. [Buy at Bookshop]

—. The Queen of Queens. New York: Bordighera Press, 2022. [Buy at Bookshop]

—. My Tarantella. New York: Bordighera Press, 2018. [Buy at Bookshop]

Jenn was such a fan of your work and this newsletter, Sean. She would have absolutely loved this.

Thank you, Sean, for this elegant tribute.