Lorine Niedecker to Louis Zukofsky, August 1952:

I wonder what the mind will be capable of doing someday without danger to the entire body?—it’s a terrible isolation though the most thrilling thing that can happen to us.

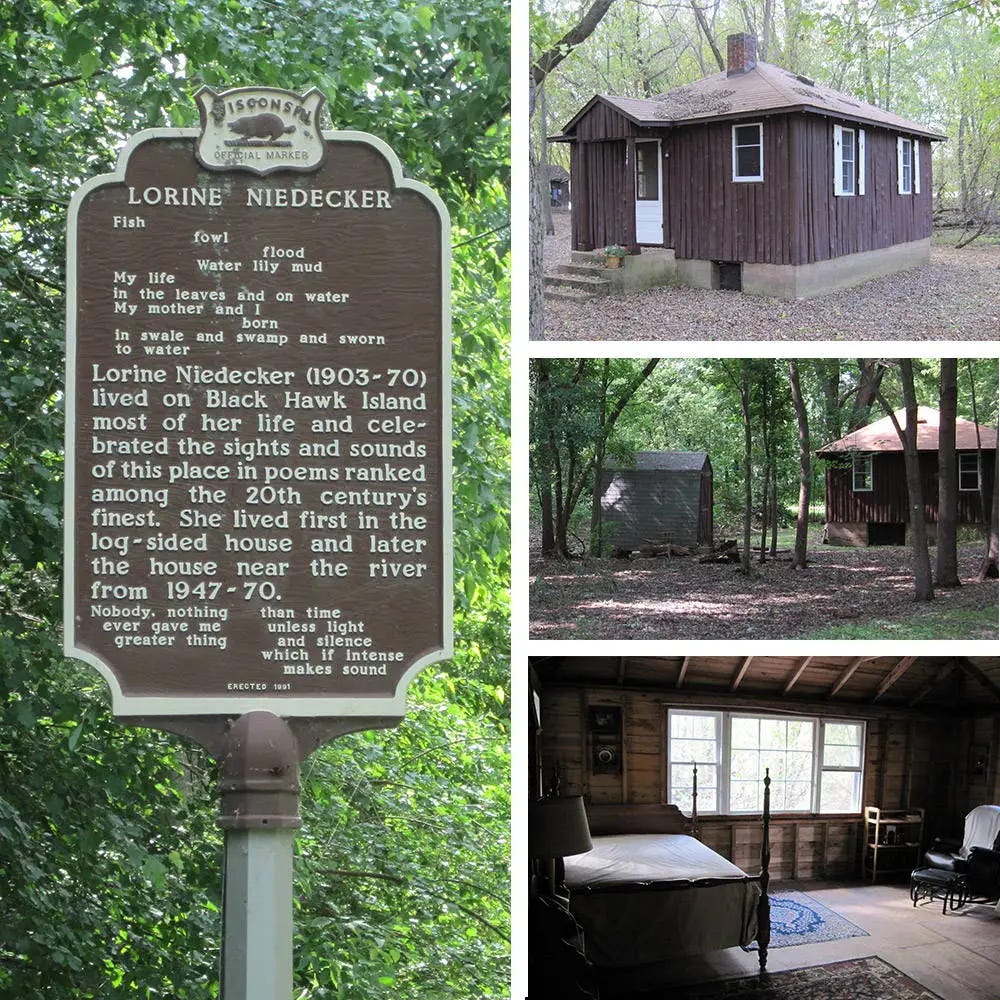

Poets can be underrated or overrated. In my opinion, Lorine Niedecker is one of the most underrated poets of all. Niedecker was born in 1903, in a cabin in rural Black Hawk Island, near Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. She lived most of her life in a cabin, and for most of her adult life she worked cleaning Fort Atkinson’s hospital. Of this work, she said: “I should draw a picture of myself covered with dust mops, pails, kitchen cleanser, cloths, brooms, etc. wondering where I am down those long halls past all those doors.”

Her modernism is the apex of sophistication, but not a sophistication wrung from New York City—it was forged in solitude in rural Wisconsin in isolated marsh mud.

Niedecker’s poetry is full of withholding and full of transformation. Her mind is the expression of yet, meaning in continuation, besides, further, and moreover. Though most (but not all!) of her poems were spare and economical, they are psychologically and philosophically expansive. She expressed apprenticeship to William Carlos Williams and indebtedness to Louis Zukofsky, but her work is at least as, if not more inventive, ambitious, and questioning as theirs.

Her geographic, experimental, and social isolation has unfairly made her an under-recognized, underdog figure. The term avant-garde is misleading: everything avant-garde becomes garde. The experimental eventually becomes the mainstream.

There is only one recording of her reading her poems, made by Cid Corman in November, 1970. The complete reading is only a little over 15 minutes. The tape runs out in mid-sentence. It is well worth your time to listen:

“wait with easy dignity / for the big change”

Niedecker was an autodidact. In 1922 she went to Beloit College to study literature, but had to leave after two years because her father couldn’t afford the tuition. When Niedecker was growing up, the family had some material comforts, but over time, and through the Great Depression her father lost more and more of their land until there were only two log structures.

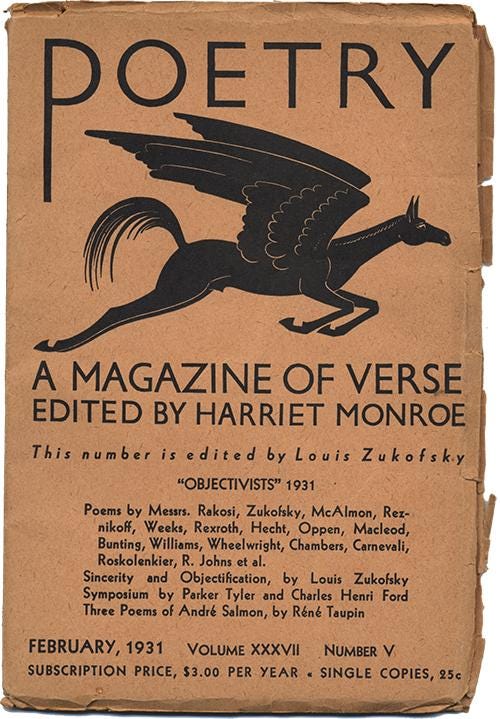

But when she read the February 1931 issue of Poetry magazine titled “Objectivists,” she perceived a ladder—a set of simpatico minds that could be a way out of her circumstances. She was aware of her psychological sturdiness, a capacity to see possibility in her poems and how they could converse with the poems in that issue.

Immediately, she sent her poems to Louis Zukofsky, the issue’s editor. When she was about 28 and he was about 27, they started exchanging letters. They became friends. Then they began a romantic relationship. She came to visit him in New York in 1933. He expected her to stay two weeks, but when she arrived at his apartment she unpacked an iron and ironing board.

The young couple got birth control advice from Dr. William Carlos Williams. They either misunderstood it or ignored it, because soon Niedecker became pregnant. Zukofsky insisted on an abortion, and they borrowed $150 (or, the equivalent of $3,419 in 2022 money) from her father. After the operation, the doctor disclosed that she’d been carrying twins. She named the twin fetuses “Lost” and “Found.”

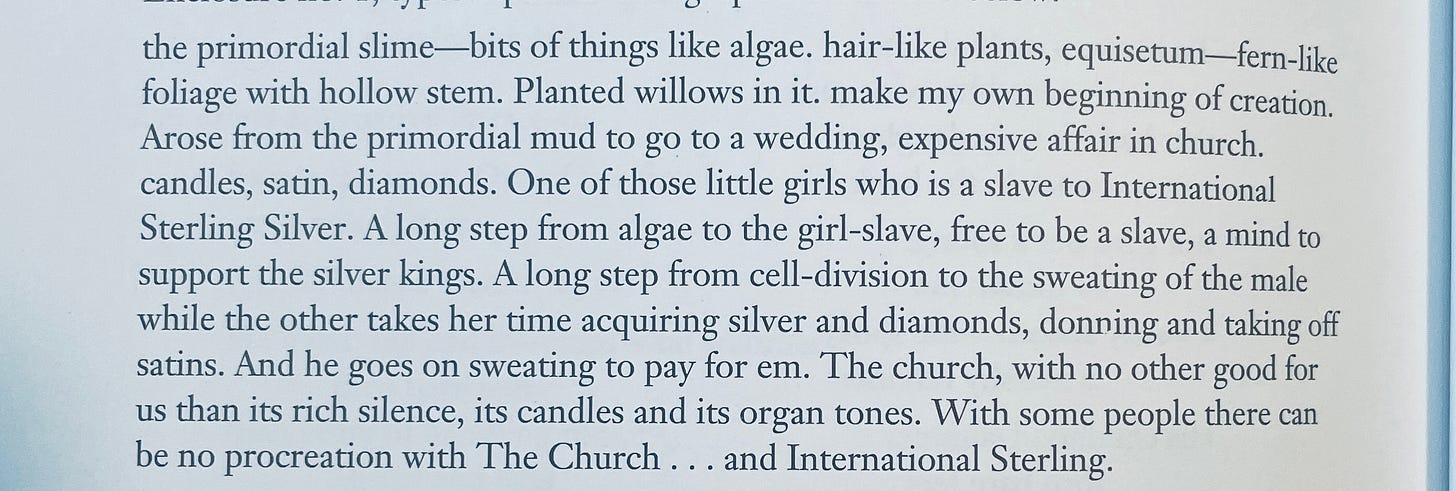

“The Church . . . and International Sterling”

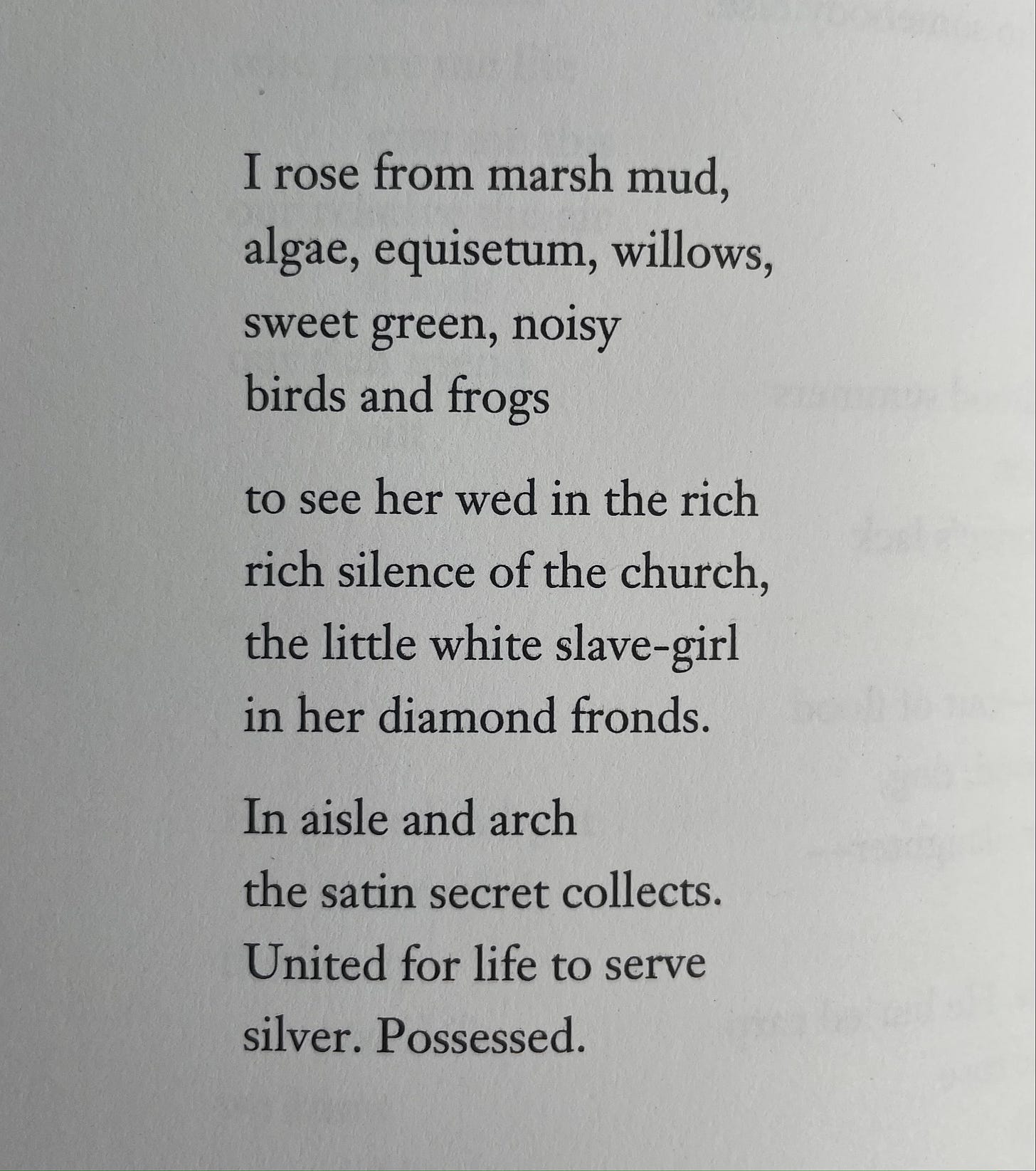

Niedecker’s poetry may appear spare, but it is dense, textured, and vocable, with a piercing intelligence. Though her subjects are drawn from the natural world, the pastoral belies the political: she was a self-created modernist, capable of dizzying leaps in scale and cultural geography. Take for example this untitled poem from June, 1945.

This poem is balanced with three quatrains and begins with something in motion—the first octave is enjambed and shows the speaker’s journey through nature. A note Niedecker wrote to James Laughlin, publisher of New Directions, further explicates the poem:

So, the poem arises out of mud and horsetails, to encompass mental cell division, a diamond—the hardest substance in the world, the “rich silence” of organ tones, and the contrast of sensuous green and the hardness of silver. The poem is about conventions, the notion of marriage as slavery, and the concept of possession—being possessed, possessing others, and self-possession.

The directness of her forms somehow occlude the poems’ materialist philosophy, really edge and riskiness. If you just read it on one level you miss the philosophical rigor of the whole thing.

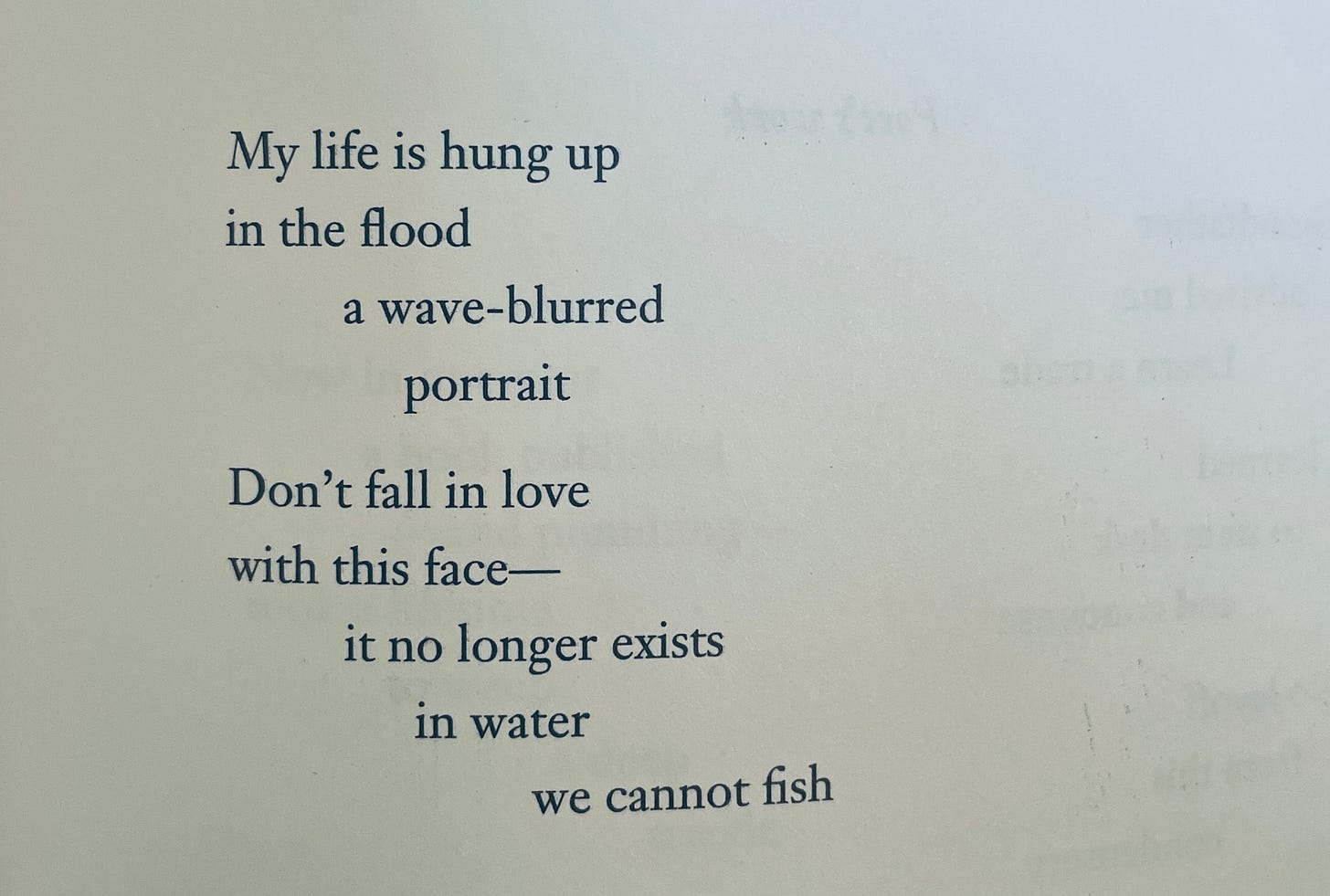

This poem, from June 1962, again uses the material, physical experience to not only demonstrate her relationship to the land, but to connect her land’s isolation to her essential notions of self.

To read a Niedecker poem thoroughly is to give oneself up to the intensity of her world. She mastered vertical movement: she sustained her energy in jewel-like forms and very short lines. She was able to somehow both use tight compression, and also expand downward, vertically.

Her books (published and unpublished) were: My Friend Tree (1961), Homemade Poems (gift book for Cid Corman, 1964), Handmade Poems (gift book for Jonathan Williams, 1964), Handmade Poems (gift book for Louis Zukofsky, 1964), T&G1: Collected Poems 1936-1966 (1969), The Earth and its Atmosphere (manuscript, 1969), The Very Veery (manuscript, 1969), and My Life by Water: Collected Poems 1936-1968 (1970).

In 1950, Niedecker described her poetics to the New Mexico Quarterly as: “the outcome of experimentation with subconscious and with folk—all good poetry much contain elements of both or stems from them—plus the rational, organizational force.”

Her work is an expression of supreme concision: a rawness that never gets bogged down in pointless description. Her language comes from physical relationships: body to self, self to land, body to land. Dissatisfied with the limits of gender and class, Niedecker made her inner space complete and expansive.

Nothing in her poems is arbitrary, overdetermined, or unnecessary. Her poems give an essential truth: all work—clam fishing, shoveling snow, making poems—comes from the body. She named her process “condensery,” in the sense of making something denser without ornament, and in the sense of changing from a gas or vapor to a liquid.

Never far from the environment, she became her language as a way of bringing the self into reality through swales, storms, marsh fog, marsh marigolds, dandelion greens, and coiled celery—what she called “the urgent wave of the verse.”

Niedecker died of a cerebral hemorrhage in December 31, 1970, which was after Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, but before Exxon came out with the first research on the impact of fossil fuels on global warming.

Her poems are not “about” nature, but about the hard truth of our indivisibility: both from our natural state, and from the brutality of colonial and capitalist structures. She demonstrates a brilliant refusal to be reduced by one or the other. We need her poems as a memento mori: there is no break from this work.

Lorine Niedecker lives! Long live Lorine Niedecker!

For further reading:

Niedecker, Lorine. Lorine Niedecker: Collected Works. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. [Buy at Bookshop]

About Sean Singer

Sean Singer Editorial Services

for “Tenderness & Gristle”

What a good introduction to Lorine Niedecker. Her ability to compress language and expand thought is exemplary. Someone to admire and learn from.

Thanks for this, Sean — fantastic. I can’t remember now when I first became aware of Niedecker’s poetry — grad school (mid-‘90s)? — but I’m grateful to learn more about her work and life through you.

“Dissatisfied with the limits of gender and class, Niedecker made her inner space complete and expansive.” Exactly this.