One Year of The Sharpener

I began publishing The Sharpener a year ago today, on November 21, 2020. I imagined a digital version of a third space, like a bookstore or a café, where people can discover poetry they didn’t know.

I had been in the habit, for several years, of posting pictures of poems to Facebook every day. I wanted to continue offering poetry for free, but I wanted a way of getting off Facebook during the regime of the former President. I also wanted to make some money for myself. Newsletter subscriptions supplement what I make from my editorial services, coaching and teaching workshops.

Then, and now, this country is in a place of great crisis. Most people can’t wrap their heads around the climate emergency, the pandemic, and political violence. Poetry is the best way I know to organize this chaos.

People need good tools. The Sharpener takes the tools of poetry—emotion, intellect—and sharpens them, so that the reader comes to know their experience through reading poems. I want to reclaim our relationship to poetry and to convene a community. This newsletter makes the kinds of conversations I’ve always wanted to have.

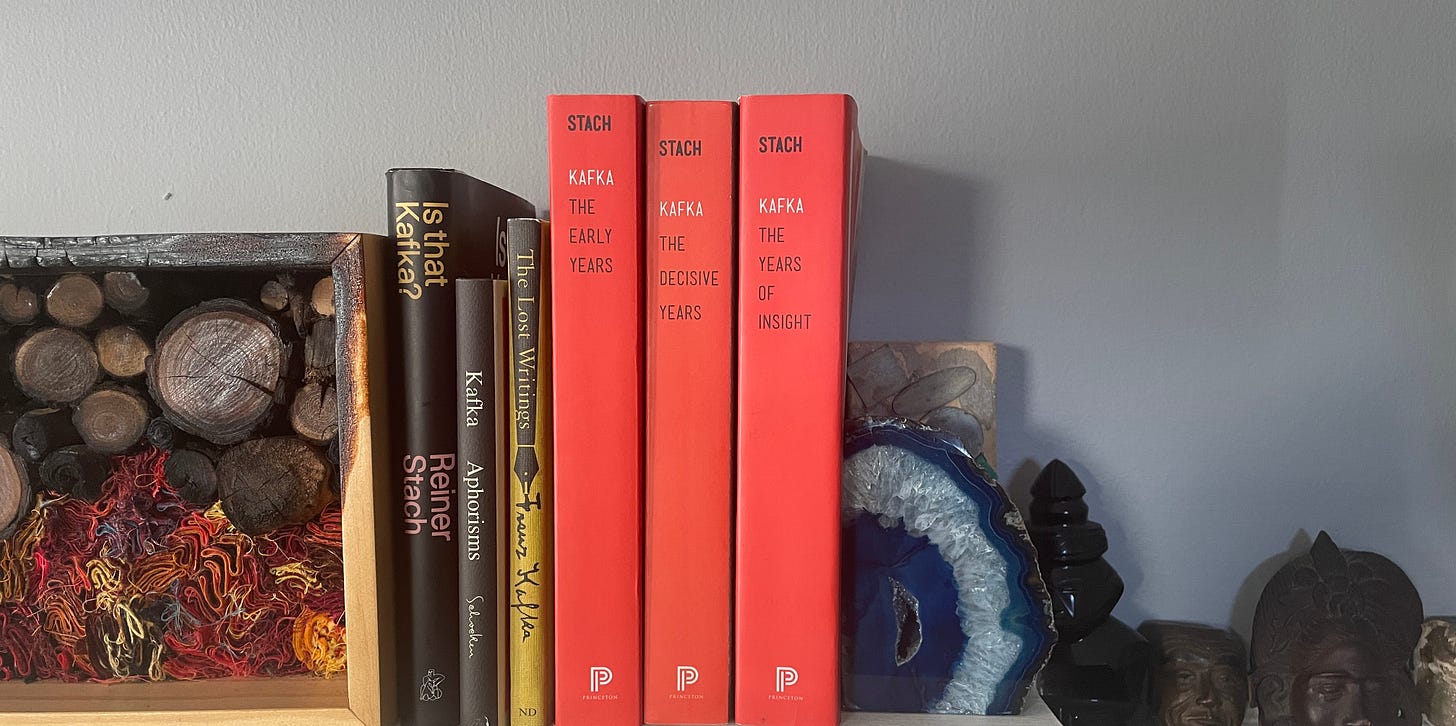

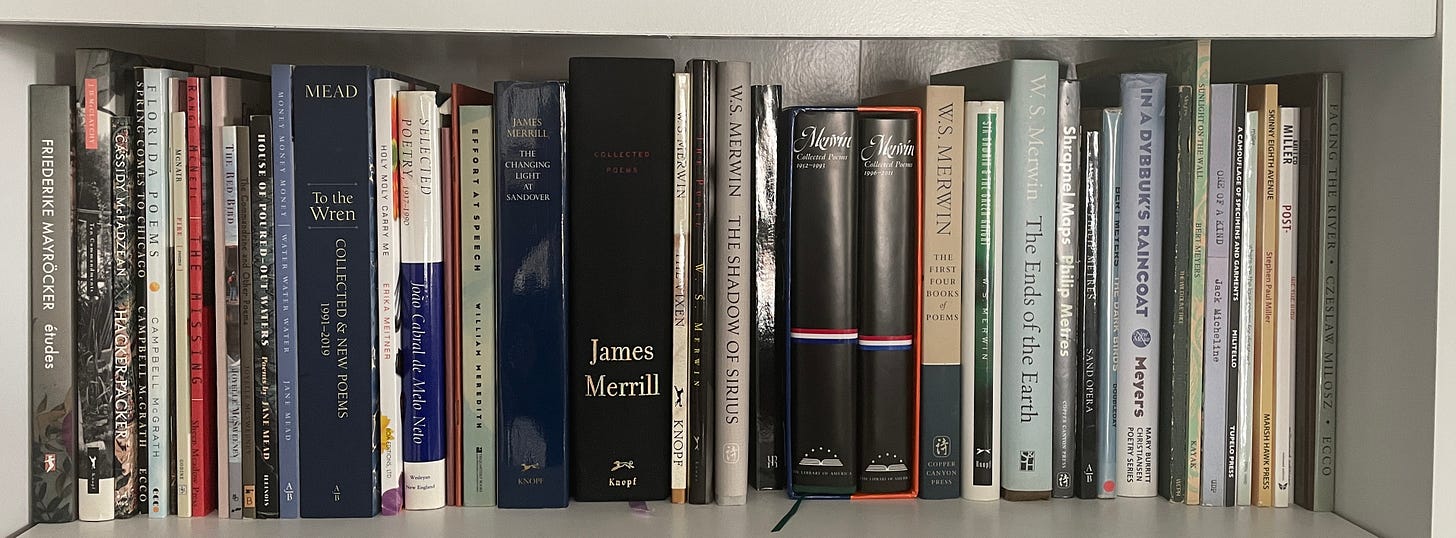

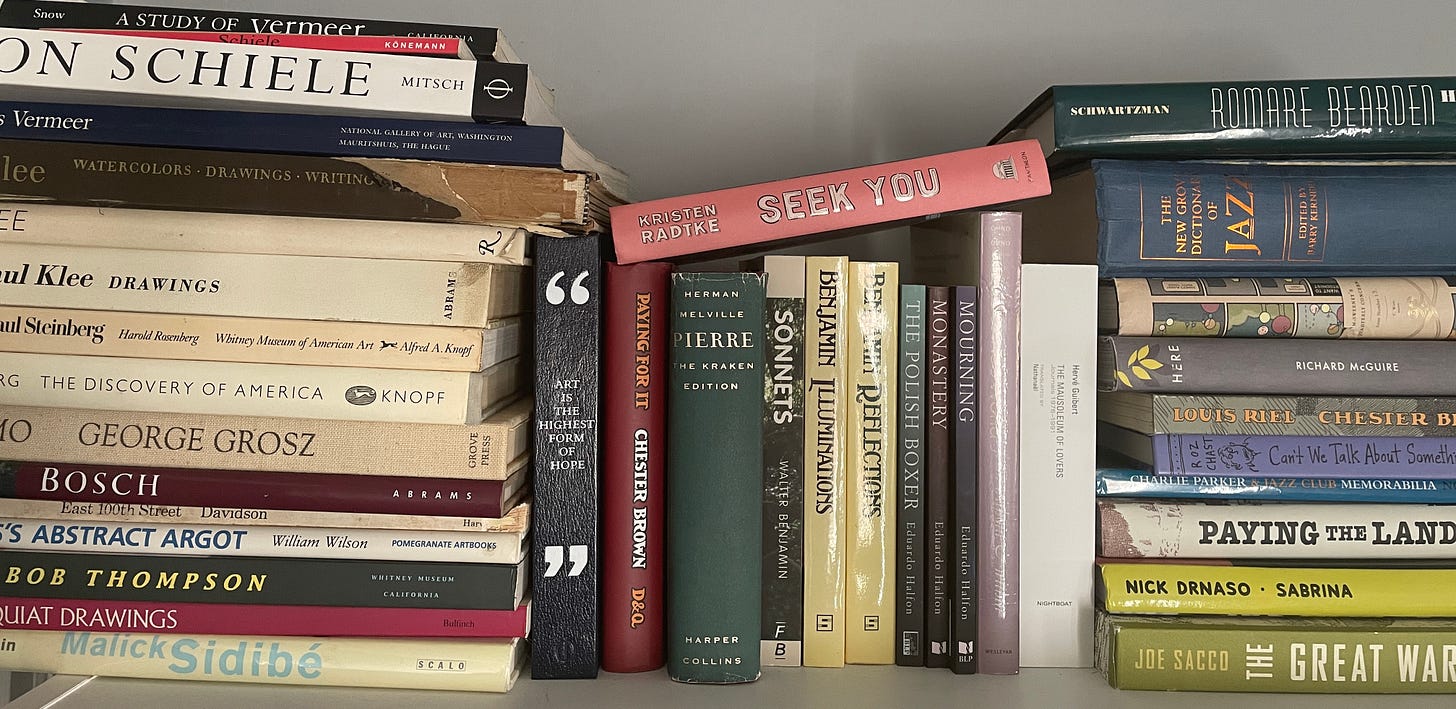

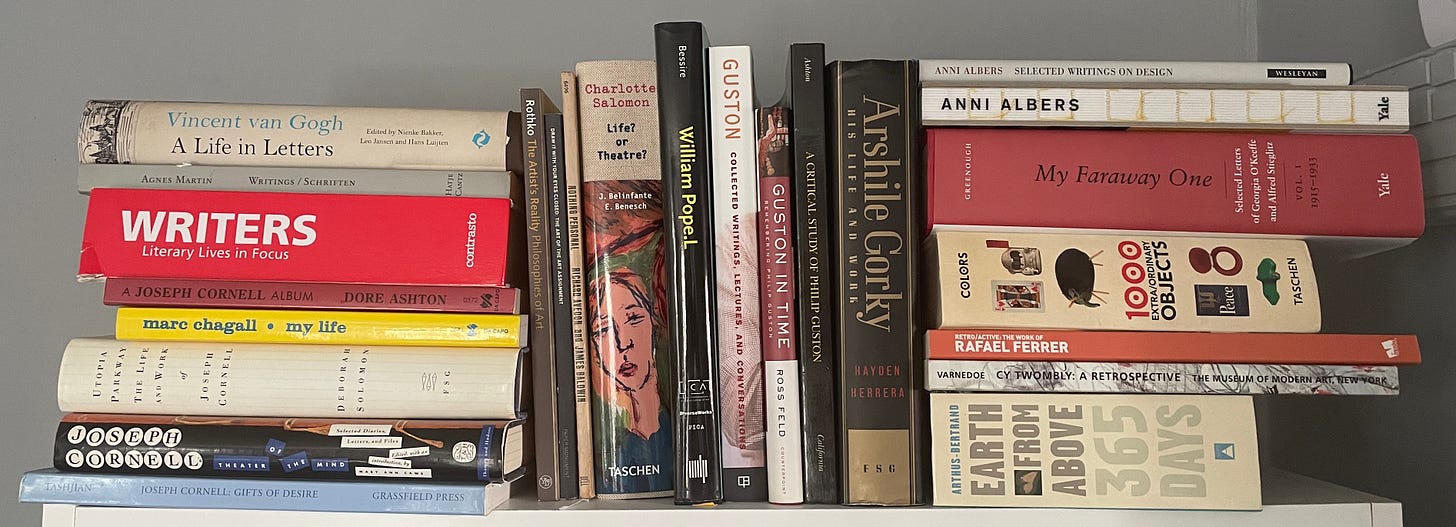

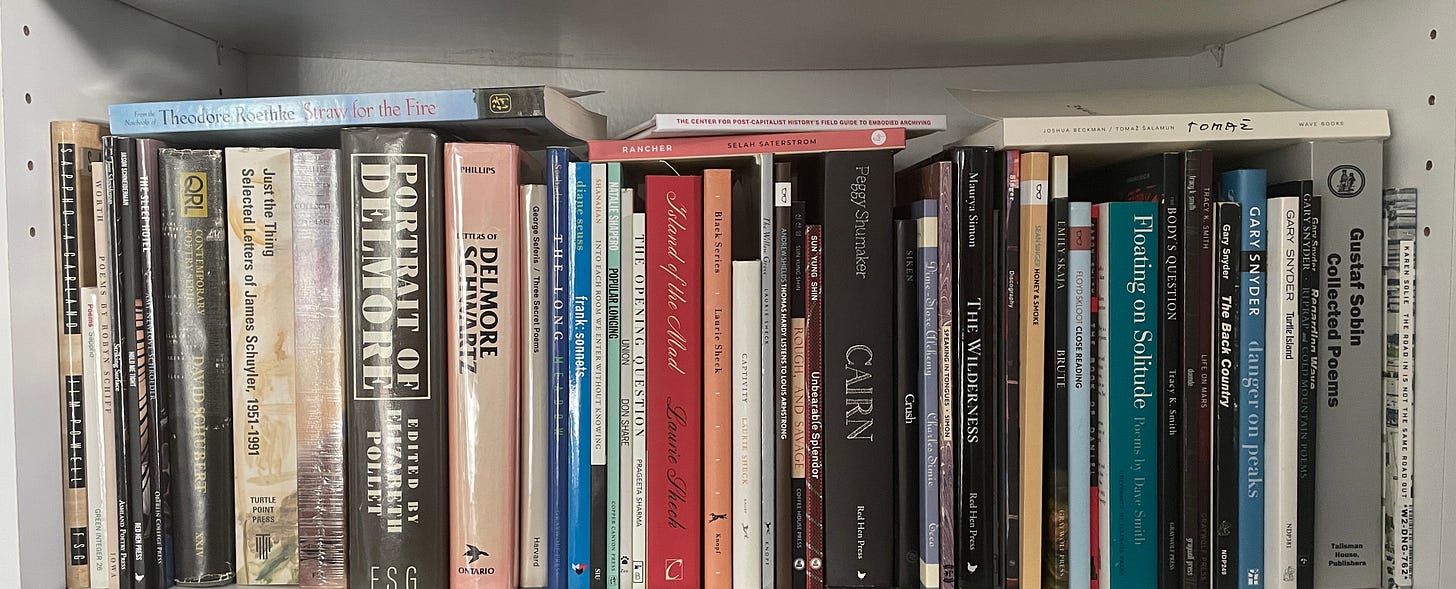

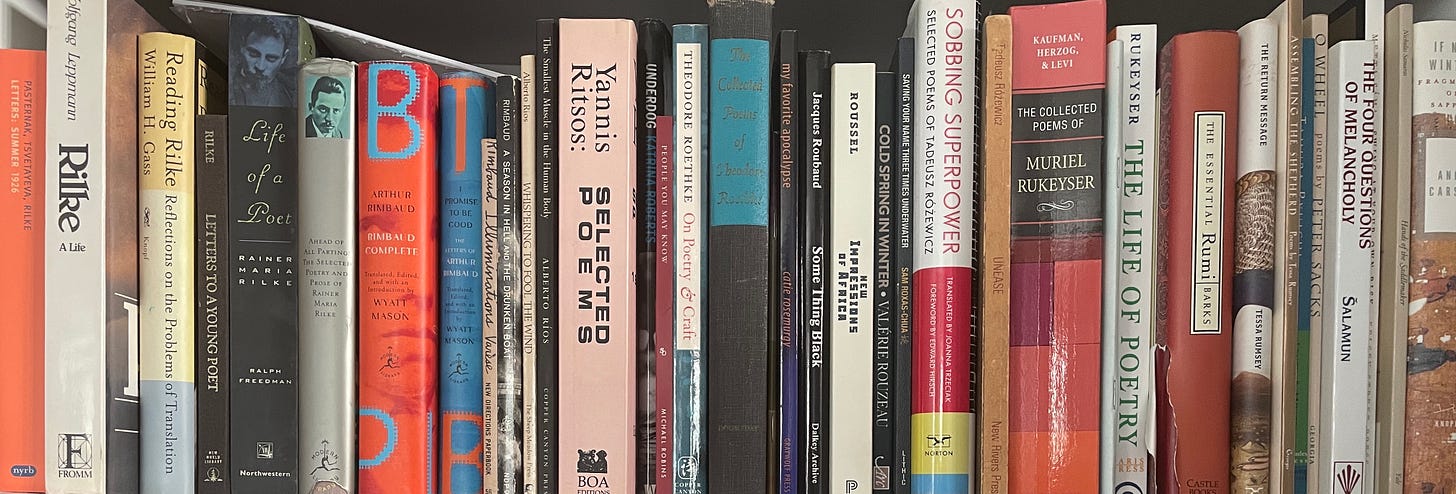

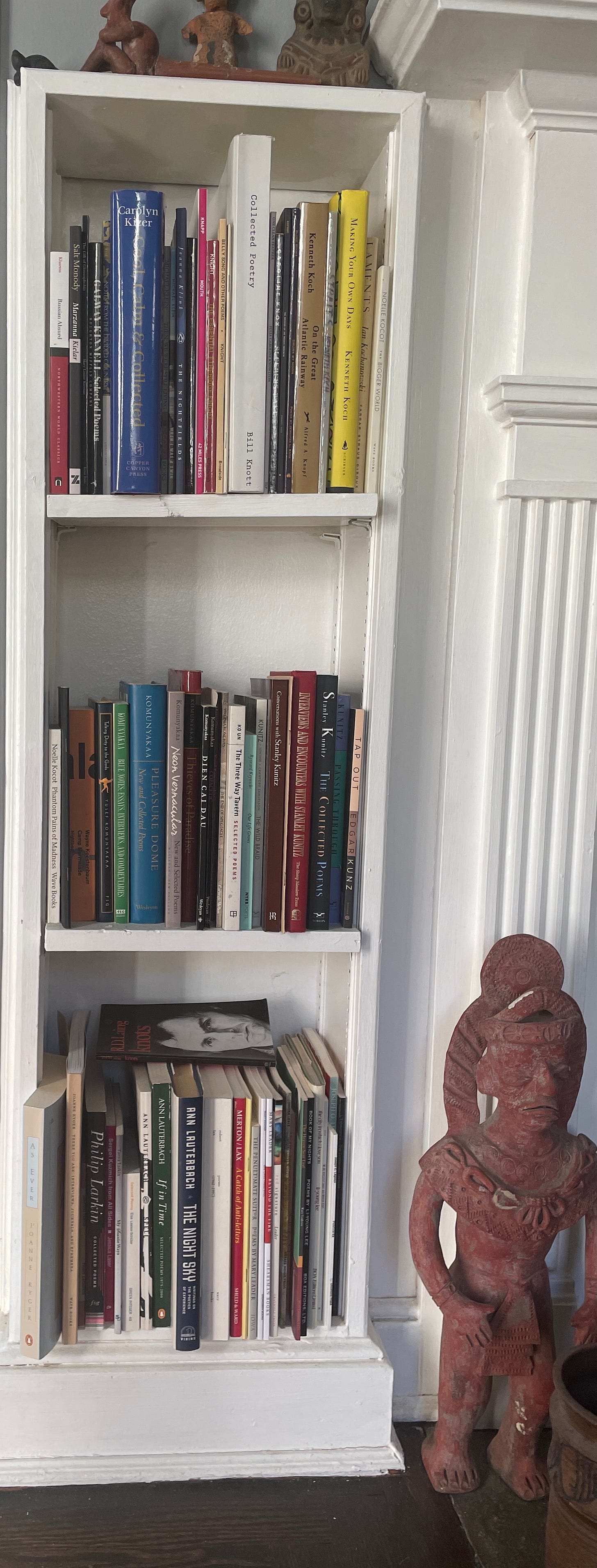

Every day, I stand before my bookcases, but I actually collate the selections for The Sharpener two or three months in advance. Sometimes I follow a loose theme—wolves, the seaside, the deaths of mothers. I share poems I’ve been thinking about. I prefer underrated or overlooked things. I look around my living room and I see this collection of a thousand books of poetry, but what I really see is my life.

I reproduce a photo of each poem on the page, to make it seem as though the reader is with me, flipping through the books. The physicality of reading is restored: the texture of the page, the shape of the letters, the act of discovery more intimate than what an algorithm can serve.

The Sharpener in Numbers

In the past year, this practice has amassed an active, growing, audience. Sharpener readers are poets and poetry professors, amateurs and experts. They are musicians and administrators; they are people I’ve known my whole life, and strangers I’ve never met. But we are all citizens in the country called Poetry.

To date, I’ve published 312 free daily posts with 1716 quotes, images, and poets. For paid subscribers, I’ve published 52 weekly posts. I’ve written about writing problems like Getting Published, Writers Block, Sincerity, and Facebook, and craft topics like Revision, Metaphor, Silence, and How to Get Back into Writing. The community has grown to 573 readers, and 129 paid subscribers.

The Sharpener and Me

The act of writing this newsletter has changed me. I sit at my kitchen table to write about things that matter to me, and I discover things that I didn’t know. Writing the newsletter is a way of coming to know myself. Stepping back, I get a sense of who I am as a poet and a person.

People get into poetry for so many reasons: some reasons stand for for self-expression, others for a kind of social capital. Both miss part of the point. Poetry has to come out of the immediacy of your experience, otherwise what is it for? Poetry must be more than decorative. It represents the subjunctive tense: wishes, doubts, and possibilities. To paraphrase Adrienne Rich, it asks the essential question What if?

The Future

Here in the United States, we’re facing a 2022 midterm that will likely determine the future of American democracy. The pandemic is looking more like an endemic: the way things are going to be for a good, long while. So why do we need to keep loyal to poetry? Why does poetry matter?

As poets, we have an important duty to defend language. When we write and read well, the work is not just a product that can be consumed and discarded like everything else. I wonder if an ironic or clever stance in poetry is a way to avoid this responsibility. To me, being responsible means accepting the incubus of the soul and being honest about it; accepting the interrelatedness of all things; and insisting that attention is a form of radical generosity.

Poetry is not a commodity. When people talk about poetry, they tend to talk about it like it lives in some kind of platonic ether. Few people care about what poets write about politics. Few people read closely, anyhow, and there will always be another poet. The reaction of poets is often defensive: self-aggrandizement, ego, self-preoccupation, paranoia. But I believe we can have a much more expansive relationship to poetry.

If our starting position is that the poem can be a conversation, where reader and writer create a joint meaning, then poetry need not be an expression of individualistic, proprietary, self-absorption. This expands the poem to let everyone in. Everyone can engage with poetry better.

It follows, then, that the success of any one poet is a victory for poetry as a whole. It lifts up the whole thing. People get confused about awards and rewards in poetry, but there are no rewards, except for doing it. Doing poetry is the reward. To make it any other way is to detach from reality, and poetry strives for something more than reality.

Poetry involves a certain amount of danger, in that you’re living at the edge of reality. But I think poems really come from our going to the edge. They ask us to be conscious of the end of experience, and to talk about it with as much clarity as we can get.

A Birthday Gift

Thank you for sharing this experience with me. By way of thanks, until the end of the year, I’m offering all readers free access to the full year of paid posts through a free, 30 day trial subscription.

If you’re a subscriber and you enjoy these weekly newsletters, please encourage your friends to subscribe, give someone a gift subscription, or share my emails with people you know who love poetry.

If you subscribe to the free, daily posts, I encourage you to become a supporting subscriber at $7 per month.

Whether you’re a paid or free subscriber, your support is what sustains The Sharpener. Thank you for being a part of this community.